![William Monk 02 - A Dangerous Mourning]()

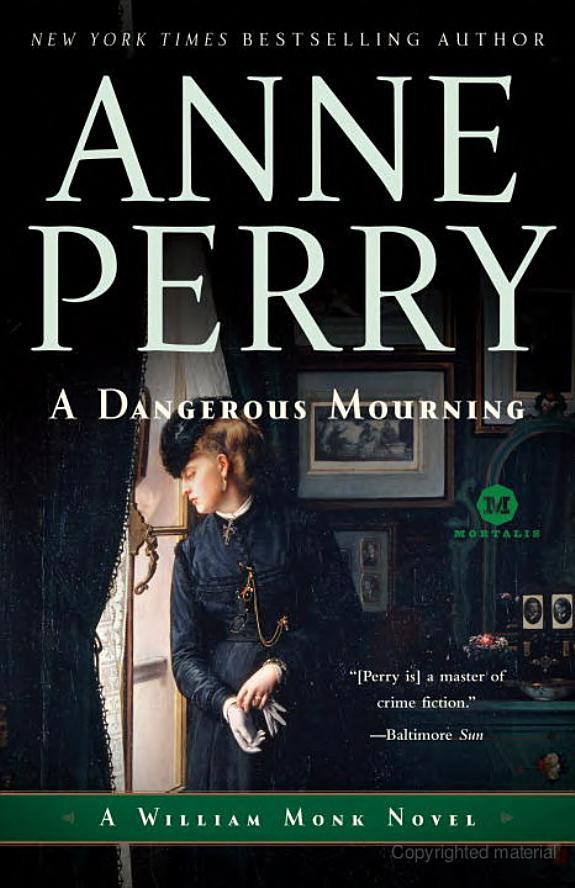

William Monk 02 - A Dangerous Mourning

rather more than a servant, but a great deal less than a guest. She was considered skilled, but she was not part of the ordinary staff, nor yet a professional person such as a doctor. She was a member of the household, therefore she must come and go as she was ordered and conduct herself in all ways as was acceptable to her mistress.

Mistress—

the word set her teeth on edge.

But why should it? She had no possessions and no prospects, and since she took it upon herself to administer to John Airdrie without Pomeroy’s permission, she had no other employment either. And of course there was not only caring for Lady Moidore to consider and do well, there was the subtler and more interesting and dangerous job to do for Monk.

She was given an agreeable room on the floor immediately above the main family bedrooms and with a connecting bell so she could come at a moment’s notice should she be required. In her time off duty, if there should be any, she might read or write letters in the ladies’ maids’ sitting room. She was told quite unequivocally what her duties would be, and what would remain those of the ladies’ maid, Mary, a dark, slender girl in her twenties with a face full of character and a ready tongue. She was also told the province of the upstairs maid, Annie, who was about sixteen and full of curiosity, quick-witted and far too opinionated for her own good.

She was shown the kitchen and introduced to the cook, Mrs. Boden, the kitchen maid Sal, the scullery maid May, the bootboy Willie, and then to the laundrymaids Lizzie and Rose, who would attend to her linens. The other ladies’ maid, Gladys, she only saw on the landing; she looked after Mrs. Cyprian Moidore and Miss Araminta. Similarly the upstairs maid Maggie, the between maid Nellie, and the handsome parlormaid Dinah were outside her responsibility. The tiny, fierce housekeeper, Mrs. Willis, did not have jurisdiction over nurses, and that was a bad beginning to their relationship. She was used to power and resented a female servant who was not answerable to her. Her small, neat face showed it in instant disapproval. She reminded Hester of a particularly efficient hospital matron, and the comparison was not a fortunate one.

“You will eat in the servants’ hall with everyone else,”Mrs. Willis informed her tartly. “Unless your duties make that impossible. After breakfast at eight o’clock we all,” she said the word pointedly, and looked Hester in the eye, “gather for Sir Basil to lead us in prayers. I assume, Miss Latterly, that you are a member of the Church of England?”

“Oh yes, Mrs. Willis,” Hester said immediately, although by inclination she was no such thing, her nature was all nonconformist.

“Good.” Mrs. Willis nodded. “Quite so. We take dinner between twelve and one, while the family takes luncheon. There will be supper at whatever time the evening suits. When there are large dinner parties that may be very late.” Her eyebrows rose very high. “We give some of the largest dinner parties in London here, and very fine cuisine indeed. But since we are in mourning at present there will be no entertaining, and by the time we resume I imagine your duties will be long past. I expect you will have half a day off a fortnight, like everyone else. But if that does not suit her ladyship, then you won’t.”

Since it was not a permanent position Hester was not yet concerned with time off, so long as she had opportunity to see Monk when necessary, to report to him any knowledge she had gained.

“Yes, Mrs. Willis,” she replied, since a reply seemed to be awaited.

“You will have little or no occasion to go into the withdrawing room, but if you do I presume you know better than to knock?” Her eyes were sharp on Hester’s face. “It is extremely vulgar ever to knock on a withdrawing room door.”

“Of course, Mrs. Willis,” Hester said hastily. She had never given the matter any thought, but it would not do to admit it.

“The maid will care for your room, of course,” the housekeeper went on, looking at Hester critically. “But you will iron your own aprons. The laundrymaids have enough to do, and the ladies’ maids are certainly not waiting on you! If anyone sends you letters—you have a family?” This last was something in the nature of a challenge. People without families lacked respectability; they might be anyone.

“Yes, Mrs. Willis, I do,” Hester said firmly. “Unfortunately my parents died

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher