![Write me a Letter]()

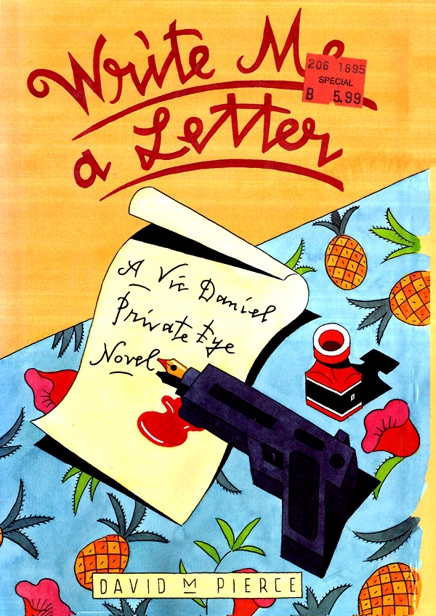

Write me a Letter

where the elite meet to shop, hop, and bop,” Willing Boy sang out after a moment. ”Up that mount on our left, which is named Mont Real, by the way—”

”As against Mont False, I suppose,” I said.

”Which means royal, not real, man,” Marlon said. ”Where the city got its name from, get it? Anyway, up that there mountain is Westmount , where all the bread is, or at least what’s left of it.”

”Where’d the rest go?” I said for something to say. ”West, man, west,” Marlon said. ”Soon as the natives in these parts started gettin’ uppity a while back, wanting their own language spoken and all that, a lot of scared Anglo money hit the road.”

”No!” I exclaimed. ”How utterly pushy. Next thing these damned Frenchies will be wanting is the vote. And then— who knows? Tumbrils may yet roll again along these cobbled streets.” At which time la petite twerp suggested that I put a sock in it as she’d seen the movie, thanks.

After we left the high-rent area we came to a part of the city that looked more like what cities were supposed to look like—tenement buildings, small businesses, sex shops, counter joints, cut-rate drugs, Jewish delis, and carpeterias. We even passed a couple of drunks arguing on a corner.

”That’s more like it,” I said, stopping carefully for a red light. ”How can you have a decent city without winos.”

”Mordecai Richler,” the tour guide said.

”So what,” I said.

”He came from around here, St. Lawrence Main, St. Denis, poor Jewish and poor Catholic fighting it out.”

”Never heard of him,” I said. ”Who did you say he played for?”

Willing Boy tossed his tresses out of his eyes and directed me left onto Beaubien, which we cruised along for a stretch. I turned down into St. Michel and drove slowly past 855, which turned out to be a wooden-shingled, steep-roofed duplex, with a small porch out front and the low white fence Mrs. Leduc had mentioned. In the yard next to it was a large snowman with a carrot nose and coal eyes, an old broom tucked under one of its rather shapeless arms. Someone in an old clunker he just managed to start pulled out from the curb a few doors up; I backed deftly into the space he left and then cut the motor.

”Now what?” Sara wanted to know.

”Now we wait awhile,” I said. ”See what happens. We might get lucky.”

”Why don’t we just knock on the door and see what happens?”

”Because we might get unlucky,” I said patiently. ”He could have friends in for tea. Large ones. He could have things called firearms, which make a lot of noise and then kill you. When I do approach him, I’d rather it was somewhere nice and public so if he does have a gun he won’t be as likely to use it and maybe he’s left it at home anyway.”

We waited awhile. I started up the motor from time to time to reheat the car. Sara toyed with the nape of Marlon’s neck from time to time; he didn’t seem to mind. After another little while he dug out a roach from one of his pockets and they both took a toke on it while I kept an uneasy eye out for guys on horses in red coats and Boy Scout hats.

It wasn’t even an hour before someone came out of Mrs. Leduc’s half of the duplex who could have been our man William, if Fats’ description had been accurate, and why would he lie about that part of it whatever else he might be lying about. The man was small, nondescript, with a receding chin and large glasses. He waved at an upstairs window, took an unsuspicious look around, checked the sky for what I don’t know, maybe passing geese, then he headed briskly off toward Beaubien.

”We better split up,” I said hastily. ”You two take him on foot, you’re smaller than me, he’s not likely to think you two drugged-out freaks are tailing him but try and look Canadian just in case. See where he goes. If he’s headed for a car parked somewhere, I’ll take him. See you back at the hotel. Go.”

They went, the twerp stopping just long enough to make a snowball and chuck it at the windscreen. I started up the car and, staying well behind the parade, followed William as far as Beaubien and then along it until he disappeared into one of the big Ms for métros. The kids tagged along after him. I drove back to the hotel, only losing my way twice and once almost.

I know what they do on a rainy night in Río but what do you do on a cold afternoon in Montreal when the salmon aren’t running? I suppose I could have gone

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher