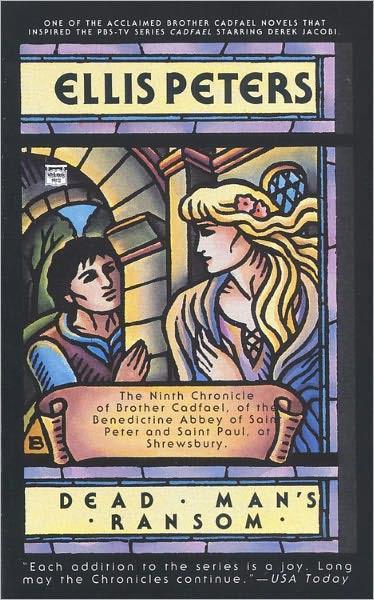

![Brother Cadfael 09: Dead Man's Ransom]()

Brother Cadfael 09: Dead Man's Ransom

uncharacteristic bitterness, but even more resignation, 'and he reproved me for doubting that the hand was God's. Sometimes I question whether his ailment of the mind is misfortune or cunning. But try to pin him down and he'll slip through your fingers every time. He is certainly very content with this death. God forgive us all our backslidings and namely those into which we fall unwitting.'

'Amen!' said Cadfael fervently. 'And he's a strong, able man, and always in the right, even if it came to murder. But where would he lay hands on such a cloth as I have in mind?' He remembered to ask: 'Did you leave Brother Wilfred to keep a close eye on things here, when you went to dinner in the refectory?'

'I wish I had,' owned Edmund sadly. 'There might have been no such evil then. No, Wilfred was at dinner with us, did you never see him? I wish I had set a watch, with all my heart. But that's hindsight. Who was ever to suppose that murder would walk in and let loose chaos on us? There was nothing to give me warning.'

'Nothing,' agreed Cadfael and brooded, considering. 'So Wilfred is out of the reckoning. Who else among us walks with a stick? None that I know of.'

'There's Anion is still on a crutch,' said Edmund, 'though he's about ready to discard it. He rather flies with it now than hobbles, but for the moment it's grown a habit with him, after so stubborn a break. Why, are you looking for a man with a prop?'

Now there, thought Cadfael, going wearily to his bed at last, is a strange thing. Brother Rhys, hearing a stick tapping, looks for the source of it only among the brothers; and I, making my way round the infirmary, never give a thought to any but those who are brothers, and am likely to be blind and deaf to what any other may be up to even in my presence. For it had only now dawned on him that when he and Brother Edmund entered the long room, already settling for the evening, one younger and more active soul had risen from the corner where he sat and gone quietly out by the door to the chapel, the leather shod tip of his crutch so light upon the stones that it seemed he hardly needed it, and could only have taken it away with him, as Edmund said, out of habit or in order to remove it from notice.

Well, Anion would have to wait until tomorrow. It was too late to trouble the repose of the ageing sick tonight.

In a cell of the castle, behind a locked door, Elis and Eliud shared a bed no harder than many they had shared before and slept like twin babes, without a care in the world. They had care enough now. Elis lay on his face, sure that his life was ended, that he would never love again, that nothing was left to him, even if he escaped this coil alive, but to go on Crusade or take the tonsure or undergo some barefoot pilgrimage to the Holy Land from which he would certainly never return. And Eliud lay patient and agonising at his back, with an arm wreathed over the rigid, rejecting shoulders, fetching up comfort from where he himself had none. This cousin, brother of his was far too vehemently alive to die for love, or to succumb for grief because he was accused of an infamy he had not committed. But his pain, however curable, was extreme while it lasted.

'She never loved me,' lamented Elis, tense and quivering under the embracing arm. 'If she had, she would have trusted me, she would have known me better. If ever she'd loved me, how could she believe I would do murder?' As indignantly as if he had never in his transports sworn that he would! That or anything.

'She's shocked to the heart for her father,' pleaded Eliud stoutly. 'How can you ask her to be fair to you? Only wait, give her time. If she loved you, then still she does. Poor girl, she can't choose. It's for her you should be sorry. She takes this death to her own account, have you not told me? You've done no wrong and so it will be proved.'

'No, I've lost her, she'll never let me near her again, never believe a word I say.'

'She will, for it will be proven you're blameless. I swear to you it will! Truth will come out, it must, it will.'

'If I don't win her back,' Elis vowed, muffled in his cradling arms, 'I shall die!'

'You won't die, you won't fail to win her back,' promised Eliud in desperation. 'Hush, hush and sleep!' He reached out a hand and snuffed out the failing flame of their tiny lamp. He knew the tensions and releases of this body he had slept beside from childhood, and knew that sleep was already a weight on Elis's smarting eyelids.

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher