![Brother Cadfael 09: Dead Man's Ransom]()

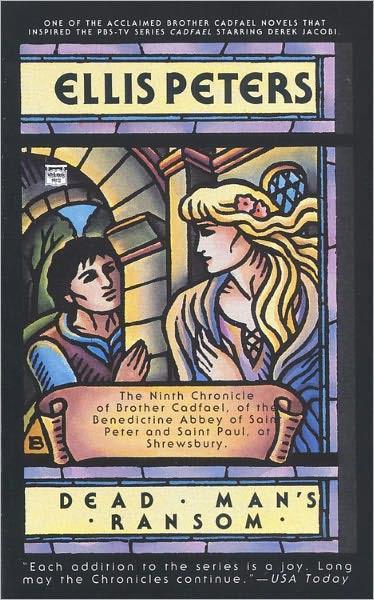

Brother Cadfael 09: Dead Man's Ransom

protection is good, but even better if backed by the practical assistance heaven has a right to expect from sensible mortals. But a war party of a hundred or more, and with one ignominious rout to avenge! Did they understand what they were facing?

'I need a weapon,' said Elis, standing aloft on the bank with feet solidly spread and black head reared towards the north, west, from which the menace must come. 'I can use sword, lance, bow, whatever's to spare... That hatchet of yours, on a long haft...' He had another chance weapon of his own, he had just realised it. If only he could get wind in time, and be the first to face them when they came, he had a loud Welsh tongue where they would be looking only for terrified English, he had the fluency of bardic stock, all the barbs of surprise, vituperation and scarifying mockery, to loose in a flood against the cowardly paladins who came preying on holy women. A tongue like a whiplash! Better still drunk, perhaps, to reach the true heights of scalding invective, but even in this state of desperate sobriety, it might still serve to unnerve and delay.

Elis waded into the water, and selected a place for one of his stakes, hidden among the water weed with its point sharply inclined to impale anyone crossing in unwary haste. By the careful way John Miller was moving, the ford had been pitted well out in midstream. If the attackers were horsed, a step astray into one of those holes might at once lame the horse and toss the rider forward on to the pales. If they came afoot, at least some might fall foul of the pits, and bring down their fellows with them in a tangle very vulnerable to archery.

The miller, kneedeep in midstream, stood to look on critically as Elis drove in his murderous stake, and bedded it firmly through the tenacious mattress of weed into the soil under the bank. 'Good lad!' he said with mild approval. 'We'll find you a pikel, or the foresters may have an axe to spare among them. You shan't go weaponless if your will's good.'

Sister Magdalen, like the rest of the household, had been up since dawn, marshalling all the linens, scissors, knives, lotions, ointments and stunning draughts that might be needed within a matter of hours, and speculating how many beds could be made available with decorum and where, if any of the men of her forest army should be too gravely hurt to be moved. Magdalen had given serious thought to sending away the two young postulants eastward to Beistan, but decided against it, convinced in the end that they were safer where they were. The attack might never come. If it did, at least here there was readiness, and enough stouthearted forest folk to put up a good defence. But if the raiders moved instead towards Shrewsbury, and encountered a force they could not match, then they would double back and scatter to make their way home, and two girls hurrying through the woods eastward might fall foul of them at any moment on the way. No, better hold together here. In any case, one look at Melicent's roused and indignant face had given her due warning that that one, at any rate, would not go even if she was ordered.

'I am not afraid,' said Melicent disdainfully.

'The more fool you,' said Sister Magdalen simply. 'Unless you're lying, of course. Which of us doesn't, once challenged with being afraid! Yet it's generations of being afraid, with good reason, that have caused us to think out these defences.' She had already made all her dispositions within. She climbed the wooden steps into the tiny bell, turret and looked out over the exposed length of the brook and the rising bank beyond, thickly lined with bushes, and climbing into a slope once coppiced but now run to neglected growth. Countrymen who have to labour all the hours of daylight to get their living cannot, in addition, keep up a day and night vigil for long. Let them come today, if they're coming at all, thought Sister Magdalen, now that we're at the peak of resolution and readiness, can do no more, and can only grow stale if we must wait too long.

From the opposite bank she drew in her gaze to the brook itself, the deep-cut and rocky bed smoothing out under her walls to the broad stretch of the ford. And there John Miller was just wading warily ashore, the water turgid after his passage and someone else, a young fellow with a thatch of black curls, was bending over the last stake, vigorous arms and shoulders driving it home, low under the bank and screened by reeds. When he

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher