![Brother Cadfael 09: Dead Man's Ransom]()

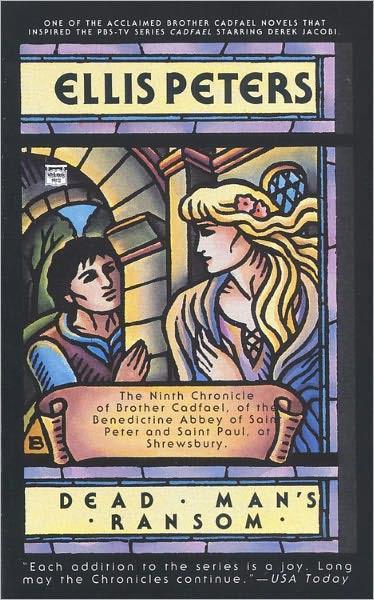

Brother Cadfael 09: Dead Man's Ransom

distant and elusive, a voice raised high and bellowing defiance.

It was almost the hour of High Mass when Alan Herbard got his muster moving out of the castle wards. He was hampered by having no clear lead as to which way the raiders planned to move, and there was small gain in careering aimlessly about the western border hunting for them. For want of knowledge he had to stake on his reasoning. When the company rode out of the town they aimed towards Pontesbury itself, prepared to swerve either northward, to cut across between the raiders and Shrewsbury, or south, west towards Godric's Ford, according as they got word on the way from scouts sent out before daylight. And this first mile they took at speed, until a breathless countryman started out of the bushes to arrest their passage, when they were scarcely past the hamlet of Beistan.

'My lord, they've turned away from the road. From Pontesbury they're making eastward into the forest towards the high commons. They've turned their backs on the town for other game. Bear south at the fork.'

'How many?' demanded Herbard, already wheeling his horse in haste.

'A hundred at least. They're holding all together, no rogue stragglers left loose behind. They expect a fight.'

'They shall have one!' promised Herbard and led his men south down the track, at a gallop wherever the going was fairly open.

Eliud rode among the foremost, and found even that pace too slow. He had in full all the marks of suspicion and shame he had invited, the rope to hang him coiled about his neck for all to see, the archer to shoot him down if he attempted escape close at his back, but also he had a borrowed sword at his hip, a horse under him and was on the move. He fretted and burned, even in the chill of the March morning. Here Elis had at least the advantage of having ridden these paths and penetrated these woodlands once before. Eliud had never been south of Shrewsbury, and though the speed they were making seemed to his anxious heart miserably inadequate, he could gain nothing by breaking away, for he did not know exactly where Godric's Ford lay. The archer who followed him, however good a shot he might be, was no very great horseman, it might be possible to put on speed, make a dash for it and elude him, but what good would it do? Whatever time he saved he would inevitably waste by losing himself in these woods. He had no choice but to let them bring him there, or at least near enough to the place to judge his direction by ear or eye. There would be signs. He strained for any betraying sound as he rode, but there was nothing but the swaying and cracking of brushed branches, and the thudding rumble of their hooves in the deep turf, and now and again the call of a bird, undisturbed by this rough invasion, and startlingly clear.

The distance could not be far now. They were threading rolling uplands of heath, to drop lower again into thick woodland and moist glades. All this way Elis must have run afoot in the night hours, splashing through these hollows of stagnant green and breasting the sudden rises of heather and scrub and outcrop rock.

Herbard checked abruptly in open heath, waving them all to stillness. 'Listen! Ahead on our right, men on the move.' They sat straining their ears and holding their breath. Only the softest and most continuous whisper of sounds, compounded of the swishing and brushing of twigs, the rustle of last autumn's leaves under many feet, the snap of a dead stick, the brief and soft exchange of voices, a startled bird rising from underfoot in shrill alarm and indignation. Signs enough of a large body of men moving through woods almost stealthily, without noise or haste.

'Across the brook and very near the ford,' said Herbard sharply. And he shook his bridle, spurred and was away, his men hard on his heels. Before them a narrow ride opened between well, grown trees, a long vista with a glimpse of low timber buildings, weathered dark brown, distant at the end of it, and a sudden lacework of daylight beyond, between the trees, where the channel of the brook crossed.

They were halfway down the ride when the boiling murmur of excited men breaking out of cover eddied up from the invisible waterside, and then, soaring loudly above, a single voice shouting defiance, and even more strangely, an instant's absolute hush after the sound.

The challenge had meant nothing to Herbard. It meant everything to Eliud. For the words were Welsh, and the voice was the voice of Elis,

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher