![Brother Cadfael 09: Dead Man's Ransom]()

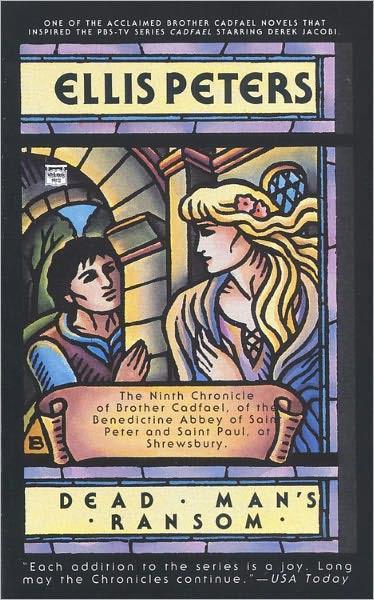

Brother Cadfael 09: Dead Man's Ransom

straightened up and showed a flushed face, she knew him.

She descended to the chapel very thoughtfully. Melicent was busy putting away, in a coffer clamped to the wall and strongly banded, the few valuable ornaments of the altar and the house. At least it should be made as difficult as possible to pillage this modest church.

'You have not looked out to see how the men progress?' said Sister Magdalen mildly. 'It seems we have one ally more than we knew. There's a young Welshman of your acquaintance and mine hard at work out there with John Miller. A change of allegiance for him, but by the look of him he relishes this cause more than when he came the last time.'

Melicent turned to stare, her eyes very wide and solemn. 'He?' she said, in a voice brittle and low. 'He was prisoner in the castle. How can he be here?'

'Plainly he has slipped his collar. And been through a bog or two on his way here,' said Sister Magdalen placidly, 'by the state of his boots and hose, and I fancy fallen in at least one by his dirty face.'

'But why make this way? If he broke loose... what is he doing here?' demanded Melicent feverishly.

'By all the signs he's making ready to do battle with his own countrymen. And since I doubt if he remembers me warmly enough to break out of prison in order to fight for me,' said Sister Magdalen with a small, reminiscent smile, 'I take it he's concerned with your safety. But you may ask him by leaning over the fence.'

'No!' said Melicent in sharp recoil, and closed down the lid of the coffer with a clash. 'I have nothing to say to him.' And she folded her arms and hugged herself tightly as if cold, as if some traitor part of her might break away and scuttle furtively into the garden.

'Then if you'll give me leave,' said Sister Magdalen serenely, 'I think I have.' And out she went, between newly, dug beds and first salad sowings in the enclosed garden, to mount the stone block that made her tall enough to look over the fence. And suddenly there was Elis ap Cynan almost nose to nose with her, stretching up to peer anxiously within. Soiled and strung and desperately in earnest, he looked so young that she, who had never borne children, felt herself grandmotherly rather than merely maternal. The boy recoiled, startled, and blinked as he recognised her. He flushed beneath the greenish smear the marsh had left across his cheek and brow, and reached a pleading hand to the crest of the fence between them.

'Sister, is she, is Melicent within there?'

'She is, safe and well,' said Sister Magdalen, 'and with God's help and yours, and the help of all the other stout souls busy on our account like you, safe she'll remain. How you got here I won't enquire, boy, but whether let out or broken out you're very welcome.'

'I wish to God,' said Elis fervently, 'that she was back in Shrewsbury this minute.'

'So do I, but better here than astray in between. And besides, she won't go.'

'Does she know,' he asked humbly, 'that I am here?'

'She does, and what you're about, too.'

'Would she not, could you not persuade her to speak to me?'

'That she refuses to do. But she may think the more,' said Sister Magdalen encouragingly. 'If I were you, I'd let her alone to think the while. She knows you're here to fight for us, there's matter for thought there. Now you'd best go to ground soon and keep in cover. Go and sharpen whatever blade they've found for you and keep yourself whole. These flurries never take long,' she said, resigned and tolerant, 'but what comes after lasts a lifetime, yours and hers. You take care of Elis ap Cynan, and I'll take care of Melicent.'

Hugh and his twenty men had skirted the Breidden hills before the hour of Prime, and left those great, hunched outcrops on the right as they drove on towards Westbury. A few remounts they got there, not enough to relieve all the tired beasts. Hugh had held back to a bearable pace for that very reason, and allowed a halt to give men and horses time to breathe. It was the first opportunity there had been even to speak a word, and now that it came no man had much to say. Not until the business on which they rode was tackled and done would tongues move freely again. Even Hugh, lying flat on his back for ease beside Cadfael under the budding trees, did not question him concerning his business in Wales.

'I'll ride with you, if I can finish my business here,' Cadfael had said. Hugh had asked him nothing then, and did not ask him now. Perhaps because his mind was wholly

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher