![Brother Cadfael 09: Dead Man's Ransom]()

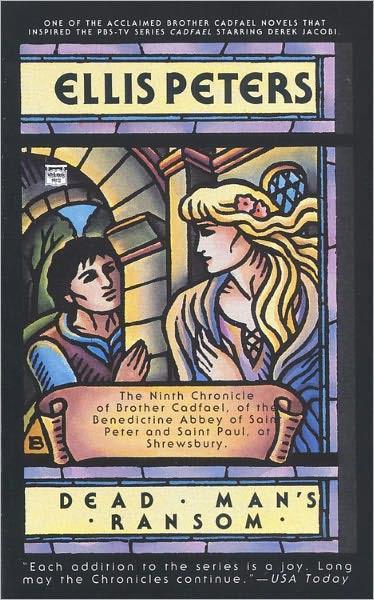

Brother Cadfael 09: Dead Man's Ransom

who had escaped hurt dropped their bows and forks and axes, and turned to help those who were wounded. And Brother Cadfael turned his back on the muddy ford and the bloodied stakes, and knelt beside Melicent in the grass.

'I was in the bell turret,' she said in a dry whisper. 'I saw how splendid... He for us and his friend for him. They will live, they must live, both... We can't lose them. Tell me what I must do.' She had done well already, no tears, no shaking, no outcry after that first scream that had carried her through the ranks of the Welsh like the passage of a lance. She had slid an arm carefully under Elis's shoulders to raise him, and prevent the weight of the two of them from falling on the head of the arrow that had pinned them together. That spared them at least the worst agony and aggravated damage of being impaled. And she had wrapped the linen of her wimple round the shaft beneath Elis's arm to stem the bleeding as best she could.

'The iron is clean through,' she said. 'I can raise them more, if you can reach the shaft.' Sister Magdalen was at Cadfael's shoulder by then, as sturdy and practical as ever, but having taken a shrewd look at Melicent's intent and resolute face she left the girl the place she had chosen, and went off placidly to salve others. Folly to disturb either Melicent or the two young men she nursed on her arm and her braced knee, when shifting them would only be worse pain. She went, instead, to fetch a small saw and the keenest knife to be found, and linen enough to stem the first bursts of bleeding when the shaft should be withdrawn. It was Melicent who cradled Elis and Eliud as Cadfael felt his way about the head of the shaft, sawed deeply into the wood, and then braced both hands to snap off the head with the least movement. He brought it out, barely dinted from its passage through flesh and bone, and dropped it aside in the grass.

'Lay them down now, so! Let them lie a moment.' The solid slope, cushioned by turf, received the weight gently as Melicent lowered her burden. 'That was well done,' said Cadfael. She had bunched the blood, stained wimple and held it under the wound as she drew aside, freeing a cramped and aching arm. 'Now do you rest, too. The one of these is shorn through the flesh of his arm, and has let blood enough, but his body is sound, and his life safe. The other, no blinking it, his case is grave.'

'I know it,' she said, staring down at the tangled embrace that bound the pair of them fast. 'He made his body a shield,' she said softly, marvelling. 'So much he loved him!'

And so much she loved him, Cadfael thought, that she had blazed forth out of shelter in much the same way, shrieking defiance and rage. To the defence of her father's murderer? Or had she long since discarded that belief, no matter how heavily circumstances might tell against him? Or had she simply forgotten everything else, when she heard Elis yelling his solitary challenge? Everything but his invited peril and her anguish for him?

No need for her to have to see and hear the worst moment of all. 'Go fetch my scrip from the saddle yonder,' said Cadfael, 'and bring more cloth, padding and wrapping both, we shall need plenty.' She was gone long enough for him to lay firm hold on the impaling shaft, rid now of its head, and draw it fast and forcefully out from the wound, with a steadying hand spread against Eliud's back. Even so it fetched a sharp, whining moan of agony, that subsided mercifully as the shaft came free. The spurt of blood that followed soon slowed; the wound was neat, a mere slit, and healthy flesh closes freely over narrow lesions, but there was no certainty what damage had been done within. Cadfael lifted Eliud's body carefully aside, to let both breathe more freely, though the entwined arms relinquished their hold very reluctantly. He enlarged the slit the arrow had made in the boy's clothing, wadded a clean cloth against the wound, and turned him gently on his back. By that time Melicent was back with all that he had asked; a wild, soiled figure with a blanched and resolute face. There was blood drying on her hands and wrists, the skirts of her habit at the knee were stiffening into a hard, dark crust, and her wimple lay on the grass, a stained ball of red. It hardly mattered. She was never going to wear that or any other in earnest.

'Now we'd best get these two indoors, where I can strip and cleanse their injuries properly,' said Cadfael, when he was assured the worst

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher