![Brother Cadfael 09: Dead Man's Ransom]()

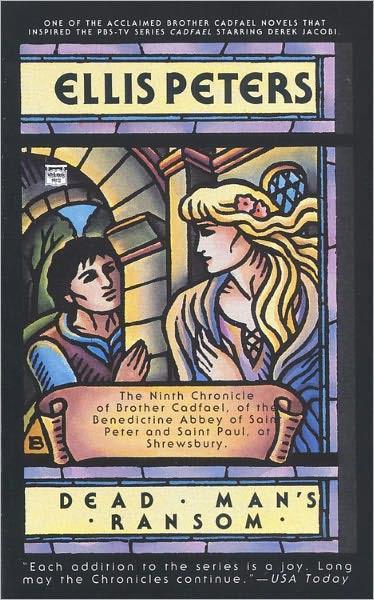

Brother Cadfael 09: Dead Man's Ransom

still a sheriff in the shire.' He turned to the bedside and stood looking down sombrely at the sleeper. 'I saw what he did. Yes, a pity...' Eliud's soiled and dismembered clothing had been removed; he retained nothing but the body in which he had been born into the world, and the means by which he had demanded to be ushered out of it, if Elis proved false to his word. The rope was coiled and hung over the bracket that held the lamp. 'What is this?' asked Hugh, as his eye lit upon it, and as quickly understood. 'Ah! Alan told me. This I'll take away, let him read it for a sign. This will never be needed. When he wakes, tell him so.'

'I pray God!' said Cadfael, so low that not even Hugh heard.

And Melicent came, from the cell where Elis lay sore with trampling, but filled and overfilled with unexpected bliss. She came at his wish, but most willingly, saw Cadfael to all appearances drowsing on his stool against the wall, signed Eliud's oblivious body solemnly with the cross, and stooped suddenly to kiss his furrowed forehead and hollow cheek, before stealing silently away to her own chosen vigil.

Brother Cadfael opened one considerate eye to watch her draw the door to softly after her, and could not take great comfort. But with all his heart he hoped and prayed that God was watching with him.

In the pallid first light before dawn Eliud stirred and quivered, and his eyelids began to flutter stressfully as though he laboured hard to open them and confront the day, but had not yet the strength. Cadfael drew his stool close, leaning to wipe the seamed brow and working lips, and having an eye to the ewer he had ready to hand for when the tormented body needed it. But that was not the unease that quickened Eliud now, rousing out of his night's respite. His eyes opened wide, staring into the wooden roof of the cell and beyond, and shortened their range only when Cadfael leaned down to him braced to speak, seeing desperate intelligence in the hazel stare, and having something ripe within him that must inevitably be said.

He never needed to say it. It was taken out of his mouth.

'I have got my death,' said the thread of a voice that issued from Eliud's dry lips, 'get me a priest. I have sinned, I must deliver all those others who suffer doubt...' Not his own deliverance, not that first, only the deliverance of all who laboured under the same suspicion.

Cadfael stooped closer. The gold, green eyes were straining too far, they had not recognised him. They did so now and lingered, wondering. 'You are the brother who came to Tregeiriog. Welsh?' Something like a sorrowful smile mellowed the desperation of his face. 'I do remember. It was you brought word of him... Brother, I have my death in my mouth, whether he take me now of this grief or leave me for worse... A debt... I pledged it...' He essayed, briefly, to raise his right hand, being strongly right handed, and gave up the attempt with a whining intake of breath at the pain it cost him and shifted, pitiless, to the left, feeling at his neck where the coiled rope should have been. Cadfael laid a hand to the lifted wrist, and eased it back into the covers of the bed.

'Hush, lie still! I am here to command, there's no haste. Rest, take thought, ask of me what you will, bid me whatever you will. I'm here, I shan't leave you.' He was believed. The slight body under the brychans seemed to sink and slacken in one great sigh. There was a small silence. The hazel eyes hung upon him with a great weight of trust and sorrow, but without fear. Cadfael offered a drop of wine laced with honey, but the braced head turned aside.

'I want confession,' said Eliud faintly but clearly, 'of my mortal sin. Hear me!'

'I am no priest,' said Cadfael. 'Wait, he shall be brought to you.'

'I cannot wait. Do I know my time? If I live,' he said simply, 'I will tell it again and again, as long as there's need, I am done with all conceal.' They had neither of them observed the door of the cell slowly opening, it was done so softly and shyly, by one troubled with dawn voices, but as hesitant to disturb those who might wish to be private as unwilling to neglect those who might be in need. In her own as yet unreasoned and unquestioned happiness, Melicent moved as one led by angelic inspiration, exalted and humbled, requiring to serve. Her bloodied habit was shed, she had a plain woollen gown on her. She hung in the half open doorway, afraid to advance or withdraw, frozen into stillness and silence

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher