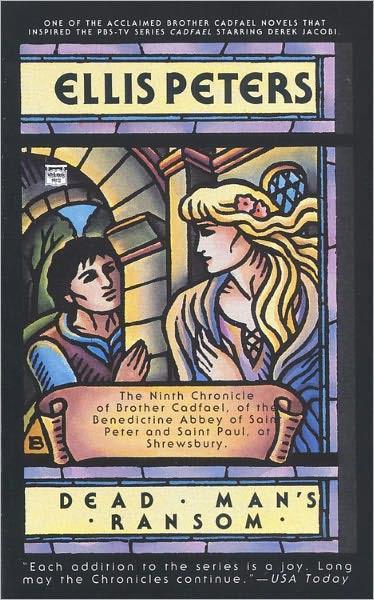

![Brother Cadfael 09: Dead Man's Ransom]()

Brother Cadfael 09: Dead Man's Ransom

thing to ask of him.'

'I will,' said Cadfael, after a brief pause to get the drift of that, for it made sense more ways than one. And he went at once to proffer the request. Hugh was already preparing to mount and ride back to the town, and Sister Magdalen was in the yard to see him go. No doubt she had been deploying for him, in her own way, all the arguments for mercy which Cadfael had already used, and perhaps others of which he had not thought. Doubtful if there would be any harvest even from her well planted seed, but if you never sow you will certainly never reap.

'Let them be together by all means,' said Hugh, shrugging morosely, 'if it can give them any comfort. As soon as the other one is fit to be moved I'll take him off your hands, but until then let him rest. Who knows, that Welsh arrow may yet do the solving for us, if God's kind to him.' Sister Magdalen stood looking after him until the last of the escort had vanished up the forested ride.

'At least,' she said then, 'it gives him no pleasure. A pity to proceed where nobody's the gainer and every man suffers.'

'A great pity! He said himself,' reported Cadfael, equally thoughtfully, 'he wished to God it could be taken out of his hands.' And he looked along his shoulder at Sister Magdalen, and found her looking just as guilelessly at him. He suffered a small, astonished illusion that they were even beginning to resemble each other, and to exchange glances in silence as eloquently as did Elis and Melicent.

'Did he so?' said Sister Magdalen in innocent sympathy. 'That might be worth praying for. I'll have a word said in chapel at every office tomorrow. If you ask for nothing, you deserve nothing.' They went in together, and so strong was this sense of an agreed understanding between them, though one that had better not be acknowledged in words, that he went so far as to ask her advice on a point which was troubling him. In the turmoil of the fighting and the stress of tending the wounded he had had no chance to deliver the message with which Cristina had entrusted him, and after Eliud's confession he was divided in mind as to whether it would be a kindness to do so now, or the most cruel blow he could strike.

'This girl of his in Tregeiriog, the one for whom he was driving himself mad, she charged me with a message to him and I promised her he should be told. But now, with this hanging over him... Is it well to give him everything to live for, when there may be no life for him? Should we make the world, if he's to leave it, a thousand times more desirable? What sort of kindness would that be?' He told her, word for word, what the message was. She pondered, but not long.

'Small choice if you promised the girl. And truth should never be feared as harm. But besides, from all I see, he is willing himself to die, though his body is determined on life, and without every spur he may win the fight over his body, turn his face to the wall, and slip away. As well, perhaps, if the only other way is the gallows. But if, I say if, the times relent and let him live, then pity not to give him every armour and every weapon to survive to hear the good news.' She turned her head and looked at him again with the deep, calculating glance he had observed before, and then she smiled. 'It is worth a wager,' she said.

'I begin to think so, too,' said Cadfael and went in to see the wager laid.

They had not yet moved Elis and his cot into the neighbouring cell; Eliud still lay alone. Sometimes, marking the path the arrow had taken clean through his right shoulder, but a little low, Cadfael doubted if he would ever draw bow again, even if at some future time he could handle a sword. That was the least of his threatened harms now. Let him be offered as counter, balance the greatest promised good.

Cadfael sat down beside the bed, and told how Elis had asked leave to join him and been granted what he asked. That brought a strange, forlorn brightness to Eliud's thin, vulnerable face. Cadfael refrained from saying a word about Elis's imminent departure, however, and wondered briefly why he kept silent on that matter, only to realise hurriedly that it was better not even to wonder, much less question. Innocence is an infinitely fragile thing and thought can sometimes injure, even destroy it.

'And there is also a word I promised to bring you and have had no quiet occasion until now. From Cristina when I left Tregeiriog.' Her name caused all the lines of Eliud's face to contract

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher