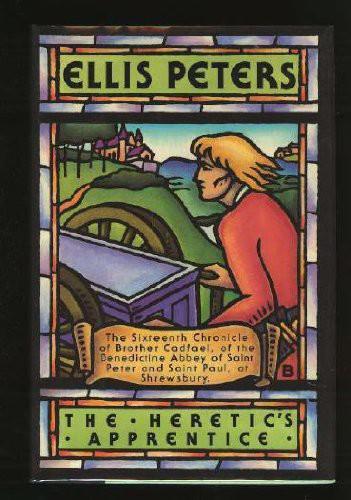

![Brother Cadfael 16: The Heretic's Apprentice]()

Brother Cadfael 16: The Heretic's Apprentice

feeble to play a full part in the order of the monastic day.

Edmund, a child of the cloister from his fourth year and meticulous in observation, had gone dutifully to the chapter house to listen to Jerome's reading. He came back to make his nightly rounds just as Cadfael was closing the doors of the medicine cupboard, and memorizing with silently moving lips the three items that needed replenishment.

"So this is where you got to," said Edmund, unsurprised. "That's fortunate, for I've brought with me someone who needs to borrow a sharp eye and a steady hand. I was going to try it myself, but your eyes are better than mine."

Cadfael turned to see who this late evening patient might be. The light within there was none too good, and the man who came in on Edmund's heels was hesitant in entering, and hung back shyly in the doorway. Young, thin, and about Edmund's own height, which was above the average.

"Come in to the lamp," said Edmund, "and show Brother Cadfael your hand." And to Cadfael, as the young man drew near in silence: "Our guest is newly come today, and has had a long journey. He must be in good need of his sleep, but he'll sleep the better if you can get the splinters out of his flesh, before they fester. Here, let me steady the lamp."

The rising light cast the young man's face into sharp and craggy relief, fine, jutting nose, strong bones of cheek and jaw, deep shadows emphasizing the set of the mouth and the hollows of the eyes under the high forehead. He had washed off the dust of travel and brushed into severe order the tangle of fair, waving hair. The colour of his eyes could not be determined at this moment, for they were cast down beneath large, arched lids at the right hand he was obediently holding close to the lamp, palm upturned. This was the young man who had brought with him into the abbey a dead companion, and asked shelter for them both.

The hand he proffered deprecatingly for inspection was large and sinewy, with long, broad-jointed fingers. The damage was at once apparent. In the heel of his palm, in the flesh at the base of the thumb, two or three ragged punctures had been aggravated by pressure into a small inflamed wound. If it was not already festering, without attention it very soon would be.

"Your porter keeps his cart in very poor shape," said Cadfael. "How did you impale yourself like this? Pushing it out of a ditch? Or was he leaving you more than your share of the work to do, safe with his harness in front there? And what have you been using to try to dig out the splinters? A dirty knife?"

"It's nothing," said the young man. "I didn't want to bother you with it. It was a new shaft he'd just fitted, not yet smoothed off properly. And it did make a very heavy load, what with having to line and seal it with lead. The slivers have run in deep, there's wood still in there, though I did prick out some."

There were tweezers in the medicine cupboard. Cadfael probed carefully in the inflamed flesh, narrowing his eyes over the young man's palm. His sight was excellent, and his touch, when necessary, relentless. The rough wood had gone deep, and splintered further in the flesh. He coaxed out fragment after fragment, and flexed and pressed the place to discover if any still remained. There was no telling from the demeanour of his patient, who stood placid and unflinching, taciturn by nature, or else shy and withdrawn here in a place still strange to him.

"Do you still feel anything there within?"

"No, only the soreness, no pricking," said the youth, experimenting.

The path of the longest splinter showed dark under the skin. Cadfael reached into the cupboard for a lotion to cleanse the wound, comfrey and cleavers and woundwort, which had got its name for good reason. "To keep it from taking bad ways. If it's still angry tomorrow, come to me and we'll bathe it again, but I think you have good healing flesh."

Edmund had left them, to make the round of his elders, and refill the little constant lamp in their chapel. Cadfael closed the cupboard, and took up the lamp by which he had been working, to restore it to its usual place. It showed him his patient's face fully lit from before, close and clear. The deep-set eyes, fixed unwaveringly on Cadfael, must surely be a dark but brilliant blue by daylight; now they looked almost black. The long mouth with its obstinate set suddenly relaxed into a wide boyish smile.

"Now I do know you!" said Cadfael, startled and pleased. "I thought when I

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher