![Cyberpunk]()

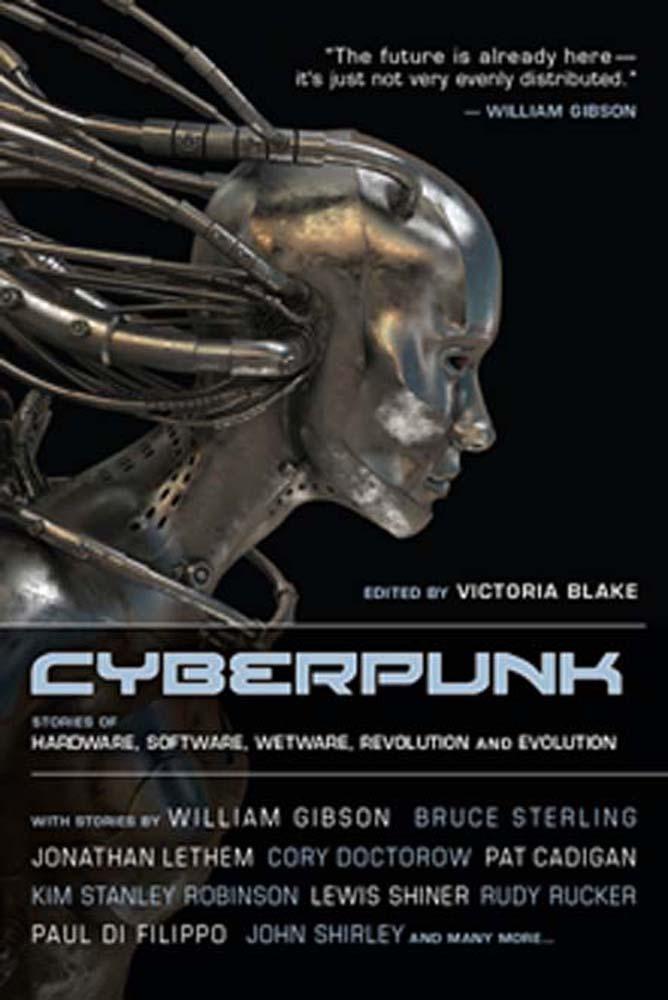

Cyberpunk

model, and the ear-nose-and-throat lining of a 67-year-old crone. And what the hell was it with those hundred-year-old F. Scott Fitzgerald novels? Those pink ballet slippers. And the insistence on calling herself “Zelda.”

Huddleston pulled himself quietly out of the bed. He lurched into the master bathroom, which alertly switched itself on as he entered. His hair was snow white, his face a road map of hard wear. The epidermal mask was tearing loose a bit, down at the shaving line at the base of his neck. He was a 25-year-old man who went out on hot dates with his own roommate. He posed as Zelda’s fictional “70-year-old escort.” When they were out in clubs and restaurants, he always passed as Zelda’s sugar daddy.

That was the way the two of them had finally clicked as a couple, somehow. The way to make the relationship work out. Al had become a stranger in his own life.

Al now knew straight-out, intimately, what it really meant to be old. Al knew how to pass for old. Because his girlfriend was old. He watched forms of media that were demographically targeted for old people, with their deafened ears, cloudy eyes, permanent dyspepsia, and fading grip strength. Al was technologically jet-lagged out of the entire normal human aging process. He could visit “his 70s” the way you might buy a ticket and visit “France.”

Getting Hazel, or rather “Zelda,” to come across in the bedroom—the term “ambivalence” didn’t begin to capture his feelings on that subject. It was all about fingernail-on-glass sexual tension and weird time-traveling flirtation mannerisms. There was something so irreparable about it. It was a massive transgressive rupture in the primal fabric of human relationships.

Not “love.” It was a different arrangement. A romance with no historical precedent, all beta pre-release, an early-adapter thing; all shakeout, with a million bugs and periodic crashes.

It wasn’t love, it was “evol.” It was “elvo.” Albert was in elvo with the curvaceous bright-eyed babe who had once been the kindly senior citizen next door.

At least he wasn’t like his dad. Stone dead of overwork on the stairsteps of his mansion, in a monster house with a monster coronary. And with three dead marriages: Mom One, Mom Two, and Mom Three. Mom One had the kid and the child support. Mom Two got the first house and the alimony. Mom Three was still trying to break the will.

How in hell had life become like this? thought Huddleston in a loud interior voice, as he ritually peeled dead pseudoskin from a mirrored face that, even in the dope-etched neural midnight of his posthuman soul, looked harmless and perfectly trustworthy. He couldn’t lie to himself—because he was a philosophy major, he formally despised all forms of cheesiness and phoniness. He was here because he enjoyed it. It was working out for him. Because it met his needs. He’d been a confused kid with emotional issues, but he was so together now.

He had to give Zelda all due credit—the woman was a positive genius at home economics. A household-maintenance whiz. Zelda was totally down with Al’s ambitious tagging project. Everything in its place with a place for everything. Every single shelf and windowsill was spic and span. Al and Zelda would leaf through design catalogs together, in taut little moments of genuine bonding.

Zelda was enthralled with the new decor scheme and clung to her household makeover projects like a drowning woman grabbing life rings. Al had to admit it: she’d been totally right about the stark necessity for new curtains. And the lamp thing—Zelda had amazing taste in lamps. You couldn’t ask for a better garden-party hostess: the canapés, the Japanese lacquer trays, crystal swizzle sticks, stackable designer porch chairs, Châteauneuf du Pape, stuff Al had never heard of, stuff he wouldn’t have learned about for 50 years. Such great, cool stuff.

She was his high-maintenance girl. A fixer-upper. Like a part-time wife, sort of kind of, but requiring extensive repair work. A good-looking gal with a brand new wardrobe, whose calcium-depleted skeletal system was slowly unhinging, requiring lots of hands-on foot rubs and devoted spinal adjustment. It was a shame about her sterility thing. But let’s face it, who needed children? Zelda had children. She couldn’t stand ’em.

What Al really wanted—what he’d give absolutely anything for—was somebody, something, somewhere, somehow, who would give him

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher