![F Is for Fugitive]()

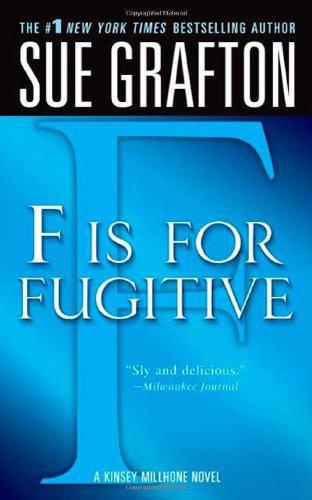

F Is for Fugitive

County Sheriff's Department, part of a complex of buildings that includes the jail. The surrounding countryside is open, characterized by occasional towering outcroppings of rock. The hills look like soft humps of foam rubber, upholstered in variegated green velvet. Across the road from the Sheriff's Department is the California Men's Colony, where Bailey had been incarcerated at the time of his escape. It amused me that in the promotional literature extolling the virtues of life in San Luis Obispo County, there's never any mention of the six thousand prisoners also in residence.

I parked in one of the visitors' slots in front of the jail. The building looked new, similar in design and construction materials to the newer portions of the high school where I'd just been. I went into the lobby, signs directing me to the booking and inmate information section down a short corridor to the right. I identified myself to the uniformed deputy in the glass-enclosed office, where I could see the dispatcher, the booking officer, and the computer terminals. To the left, I caught a glimpse of the covered garage where prisoners could be brought in by sheriffs' vehicles.

While arrangements were being made to bring Bailey out, I was directed to one of the small, glass-enclosed booths reserved for attorney-client conferences. A sign on the wall spelled out the rules for visitors, admonishing us that there could only be one registered visitor per inmate at any one time. We were to keep control of children, and any rude or boisterous conduct toward the staff was not going to be tolerated. The restrictions suggested past scenes of chaos and merriment I was already wishing I'd been privy to.

I could hear the muffled clanking of doors. Bailey Fowler appeared, his attention focused on the deputy who was unlocking the booth where he would sit while we spoke. We were separated by glass, and our conversation would be conducted by way of two telephone handsets, one on his side, one on mine. He glanced at me incuriously and then sat down. His demeanor was submissive and I found myself feeling embarrassed in his behalf. He wore a loosely structured orange cotton shirt over dark gray cotton pants. The newspaper photograph had shown him in a suit and tie. He seemed as bewildered by the clothing as he was by his sudden status as an inmate. He was remarkably good-looking: grave blue eyes, high cheekbones, full mouth, dark blond hair already in need of a cut. He was a tired forty, and I suspected circumstances had aged him overnight. He shifted in the straight-backed wooden chair, clasping his hands loosely between his knees, his expression empty of emotion.

I picked up the phone, waiting briefly while he picked up the receiver on his side. I said, "I'm Kinsey Millhone."

"Do I know you?"

Our voices sounded odd, both too tinny and too near.

"I'm the private investigator your father hired. I just spent some time with your attorney. Have you talked to him yet?"

"Couple of times on the phone. He's supposed to stop by this afternoon." His voice was as lifeless as his gaze.

"Is it all right if I call you Bailey?"

"Yeah, sure."

"Look, I know this whole thing's a bummer, but Clemson's good. He'll do everything possible to get you out of here."

Bailey's expression clouded over. "He better do something quick."

"You have family in L.A.? Wife and kids?"

"Why?"

"I thought there might be someone you wanted me to get in touch with."

"I don't have family. Just get me the hell out of here."

"Hey, come on. I know it's tough."

He looked up and off to one side, anger glinting in his eyes before the brief show of feeling subsided into bleakness again. "Sorry."

"Talk to me. We may not have long."

"About what?"

"Anything. When'd you get up here? How was the ride?"

"Fine."

"How's the town look? Has it changed much?"

"I can't make small talk. Don't ask me to do that."

"You can't shut down on me. We have too much work to do."

He was silent for a moment and I could see him struggle with the effort to be communicative. "For years, I wouldn't even drive through this part of the state for fear I'd get stopped." Transmission faltered and came to a halt. The look he gave me was haunted, as if he longed to speak, but had lost the capacity. It felt as if we were separated by more than a sheet of glass.

I said, "You're not dead, you know."

"Says you."

"You must have known it would happen one day."

He tilted his head, doing a neck roll to work the tension

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher