![Hokkaido Highway Blues]()

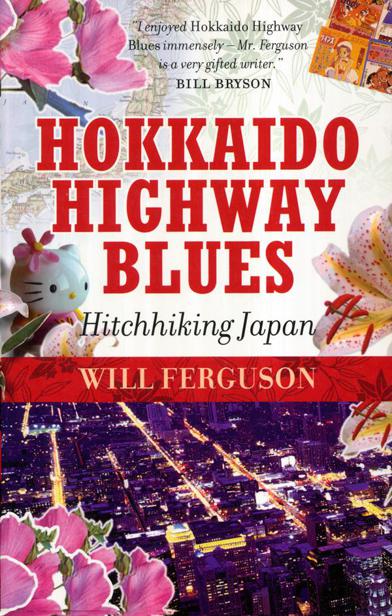

Hokkaido Highway Blues

that was remarkably advanced for its age, especially when lined up against the literally minded morality plays that were standard fare in European courts at about the same time. (“Oh, No! Scratch the Devil is eating Lazy Child! Only Virtuous Son and Loyal Daughter can save him.”)

Zeami was heralded as a genius during his lifetime, a legend of truly theatrical proportions. Mind you, it helped that Zeami—as well as being an artistic genius—was also the homosexual lover of the reigning shōgun. In a very real sense, Zeami slept his way to the top. Alas, when the Shogun died, Zeami lost his patron, and the next ruler was—ahem—less enamored with the artistry of Zeami than was his predecessor. On the pretext that the upstart Noh master was hoarding artistic secrets for himself, the new Shogun sent Zeami into exile, to the island at the edge of the world. Zeami spent his last years in obscurity, chilled to the bone and bitterly lonely. Zeami died on Sado, a broken man. His art lived on. And on and on and on and on... If you have ever tried to sit through an evening of Noh theater, you will understand what I’m speaking about.

Noh has been described as “total theater,” combining as it does music, mime, dance, poetic recitals, masked costumes, and tonal chants. It is also a theater of restraint. The tension comes not from plot, but from atmosphere, much of it supernatural. The performers are usually masked, they walk with a gliding hesitant step, and the scenes unfold like slowly transforming tableaus—all to the accompaniment of shrill flutes, sudden yelps, arbitrary drumbeats, and slow boiling moans. Noh is haunting and disturbing and deep—for about ten minutes. After that, the hours slow down to a glacial pace and the movements appear to be made under deep water. It is beyond somnolent. It is boring. Profoundly, exquisitely, existentially boring.

Zeami’s texts on Noh, once ground-breaking and avant garde, have fossilized. It is a theater of ghosts. A museum piece. The plays revolve around the cycle of karma, of death and rebirth, and the longings that tie us to this world of illusions. Certainly, the performances proceed at about the speed one expects eternity to move.

A friend of mine was studying theater in Japan and he was constantly trying to convince me that I did in fact love Noh. This friend, who was English, naturally (the English have an almost heroic capacity for boredom), would drag me to touring performances and gasp and gush over the way the lead player would hold his fan. “Do you see that!” he’d say. “The lead actor is holding his fan upside down.” My friend was, like most hardened fans, disdainful of the competition. “Noh is far deeper than the type of cheap catharsis you get from melodrama or kitchen-sink realism. And it is not simply spectacle, either. Kabuki, with its blood-and-thunder excess and extravagant costumes, is crass. But Noh... Noh is meditative.”

“And seditative,” I said.

“And yet,” he would insist, all empirical evidence to the contrary, “it is very exciting. Noh operates on many levels. Underneath it is tension—this tension that is almost unbearable.”

“Tell me about it.”

My friend was getting exasperated. “I don’t know why I even try to enlighten you. Listen,“ he’d say. “Ezra Pound helped translate Noh plays into English. Brecht was greatly influenced by Noh. W B. Yeats felt that it reached new levels of suggestive art.”

“Name drop all you want,” I said. “It makes no difference. Noh is still Noh. It’s like attending the opera or going to the dentist. You don’t enjoy it, you endure it.”

I would concede one point. The masks of Noh were sublime. The female masks in particular. (Like Kabuki, Noh is still a primarily male domain.) Poised between expressions, they are capable of all expressions. During performances of Noh, I have seen—though I would never admit this to my Noh-loving friend—how the masks seem to change moods on stage, so effective are the postures and gestures of the performers.

Perhaps my English friend was right. Perhaps Noh truly is the essence of Japanese society. Masks that have incredible depth, feelings that are restrained, emotions turned inward, silences that fester, sudden bursts, violent emotion, lifetimes of regret. Or maybe it is simply a very old and dated art form. Either way, I would not attend another evening of Noh at gunpoint.

Instead, I spent my time on Sado Island

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher