![Hokkaido Highway Blues]()

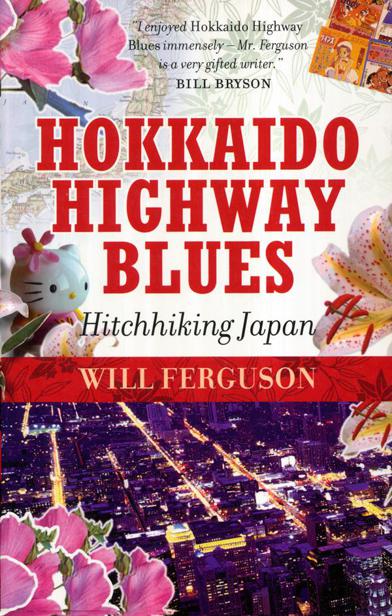

Hokkaido Highway Blues

It is a rattle really, a dry hollow sound that nudges the gods awake. You bow again, make your silent petition, and clap twice more before you step away, making sure not to turn your back on the god enshrined within, behind the mirror.

At the Grand Imperial Shrine of Udo Jingu, the atmosphere is more festive than sacred. Souvenir shops and snack-food stalls flank the approach, and visitors pass through a gauntlet of distractions on their way to the shrine. Men snap your photo and then try to sell you a copy. Round-faced ladies in aprons offer soft ice-cream cones and fried squid impaled on sticks. The smells swirl like oil and water. You catch the sweet scent of octopus steamed in dough. Snails, still in shell, simmer in broths. Trinkets and toys and yells of welcome ricochet around you. Cartoon characters, superheroes, and the god-son Ninigi-no-Mikoto are rendered in the same pink plastic and they all compete for the same jingle of coin in cup. Stalls sell good-luck charms and talismans and sacred tablets. And right smack beside them are fake doggy-do and large novelty buttocks. Everything is jumbled up in postmodern anarchy.

The approach to Udo Jingu bustles, and the closer you get to the main altar, the thicker the crowds, the quicker the tempo. Touring parties march through in phalanxes: schoolgirls in sailor uniforms, boys in brush-cuts and school caps. There are couples, new and unsure and excruciatingly aware of each other’s presence, couples comfortable, couples sullen, and couples past caring. They move like tributaries through the main torii gate. The sound and scent of the sea increases as you approach. A wooden boardwalk descends in steps along the cliff face. Waves break below, rolling up against the Devil’s Washboard. People begin hurrying as they near the cave.

The sun is oppressive. It shimmers in a haze. The world is overexposed, reflective surfaces are painful to look at, the colors washed out. But here, inside the womb of the cave, the shadows are damp and the air is wet. The cave breathes, and its exhalations are cool against your skin. Ah... Unn...

Your eyes slowly adjust to the dark, and details emerge. The shrine takes form, appearing from the murk like an image on a photographic plate. Sounds: whispering voices, dry rattles, and the hollow plonk of water dripping.

The shrine roof is in copper green, its angles fluid. It has the slope of a caravan tent. The style harkens back to the Mongolian steppes and the temporary tents of nomadic tribes. A message embodied in the very architecture of Shinto: The world is in flux, life moves, the rivers flow, and even the homes of the gods are but temporary shelters. Someday they, too, will be folded down like tents and put away.

I buy a bag filled with small clay pebbles and go outside to try my luck. In front of the cave a wooden balcony juts out over a jumble of boulders and salt spray. The sea. throws herself up against the cliff face again and again, but the shrine remains just out of reach, tucked into its cave.

In among the sea rubble, at the bottom of the cliff, is a large misshapen boulder called “Turtle Rock,” and atop the turtle’s back is a shimenawa rope, looped in a circle. The rope signifies the presence of a kami and marks the area inside the circle as hallowed. Being (a) a Westerner and (b) a male, my first thought at seeing this holy circle, perched atop a large boulder at the bottom of a cliff, is to wonder, “How the heck did they ever get that rope down there?” I imagine it is one of the duties of the novice priests. “Send Hiroshi down, he’s the new guy.” Or maybe they tossed it, Hula Hoop style. The mysteries of the universe never held such appeal for me as the mystery of how they got that rope out there onto that boulder.

The circle on Turtle Rock is part of a sacred shooting gallery. Remember the clay pebbles I bought earlier? It is time to win favor with the gods. At Udo Jingu you lean over and toss the pebbles at the rock. If they land and stay within the circle you will be rewarded with great fortune, long life, good health—the usual stuff. People crowd the edge of the boardwalk, laughing and flinging pebbles. The sea is afloat with them, they cover boulder tops and rock ledges like rabbit droppings. Mounds of pebbles are inside the rope circle, but most have bounced out. Many are wildly off the mark. Not me. When it comes to tossing clay pebbles onto large rocks, I am pretty well the Omnipotent Master

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher