![Hokkaido Highway Blues]()

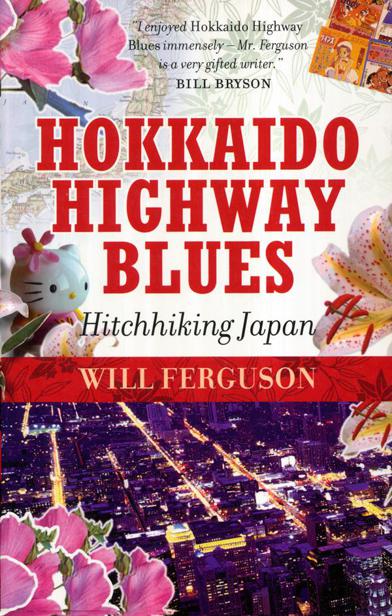

Hokkaido Highway Blues

enough as it was.

Mr. Nakamura stumbled over to see me off. “Come on, Bobby. We drink some saké with my lovely wife, you never met my wife, I want you meet my wife. Don’t go.” He reached out and held on to me. “Thank you come my home. I am an old man. Thank you.”

I slid free of his embrace and stepped off the entrance platform into my shoes. They had been turned around for me, facing the door, in that ambivalent gesture of hosts in Japan.

From the entranceway, Mr. Nak looked at me, his expression no longer Chaplinesque. “Why?” he said, “Why?”

I understood the question, but I had no answer. How could I? Me, a milk-fed pup who has never cowered in caves with a sharpened stick, who never surrendered anything, never died and was never reborn every dawn.

I couldn’t even say goodnight. My throat tight, I bowed deeply. When I came up, Mr. Nakamura had straightened himself into a perfect soldier’s stance. He looked at me from across generations, from across oceans. His jaw was set like a man’s fighting back fear. He raised his hand.

“No,” I said. “No. Don’t.”

He saluted me. Crisp and precise, and I fled, fumbling with the door, bowing hurriedly a few more times, stepping on my shoe heels, pulling the door closed behind me. He didn’t have to do that. He didn’t.

I hurried through the streets blindly and for the first time in years, I began to cry.

10

THERE IS A cherry tree in the village of Asamimura they call Uba-zakura, the Milk Nurse Cherry Tree. It is said to blossom on the same day every year, the sixteenth day of the second month of the old lunar calendar, the anniversary of the death of O-sodë, a devoted wet nurse who offered her soul in place of a sick child’s. The child survived; the nurse died. Her spirit lives on in the tree. In Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things , Lafcadio Hearn writes, “Its flowers, pink and white, were like the nipples of a woman’s breasts, bedewed with milk.”

Another tree blossoms on the anniversary of a samurai’s ritualistic suicide. Yet another contains the soul of a child. Another, the soul of a young man.

The imagery of the sakura is problematic. It has long been entwined with notions of birth and death, beauty and violence. Cherry blossoms are central to the Japanese worship of nature, a mainstay of haiku, flower vases, and kimono patterns, and yet... the sword guards of samurai warriors also bore the imprints of sakura as a last, wry reminder of the fleetingness of life just prior to disembowelment.

But the starkest image of sakura is that of the Ishiwari-zakura, the Stone-splitting Cherry Tree, in the northern city of Morioka. Here, a cherry tree took root and grew in a small crack in a very large boulder. Over the years the tree has grown, splitting the vast boulder in two and emerging from it like life out of stone-gray death. The power of beauty to shatter stone; as brutal and sublime as any sword.

* * *

I returned to the Nakamura house the next afternoon just as they were stepping out.

“Hello, Willy-chan!” said Mr. Nakamura, without a flicker of what had passed between us the night before. In Japan, saké time is dreamtime; all is forgotten in the light of dawn. Mr. Nakamura, I noticed, no longer addressed me as Mr. but as “chan,” a suffix reserved for friends and small children. As a Westerner I would always be a bit of both.

“You stay our house tonight,” said Mr. Nakamura. “Hotel is too expensive. You stay with us. I see you after, okay, Willy-chan?”

Chiemi and Ayané were on their way out. Ayané was dressed in the standard uniform: a pink sundress, little purse, and a straw sun hat with a ribbon around it. There is nothing cuter in this world than a little Japanese girl in a sun hat with Meca-Godzilla under her arm. Chiemi was carrying a parasol and a boxed lunch tied up neatly with a scarf.

“Ayané and I are having our cherry blossom picnic today, why don’t you come?”

It was the third time I had been to Kenroku Park in as many days, but I didn’t tell her this. It was a nice enough park. Same old pond, same old waterfall. Ayané was ahead of us, examining an especially interesting bunch of pebbles, having granted me joint custody of Meca-Godzilla. Which is to say, I got to carry him while she was out on her geological expeditions. Chiemi and I were near the water’s edge when Chiemi pointed out the lantern.

“Do you see the lantern?” she said, and we

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher