![I Hear the Sirens in the Street]()

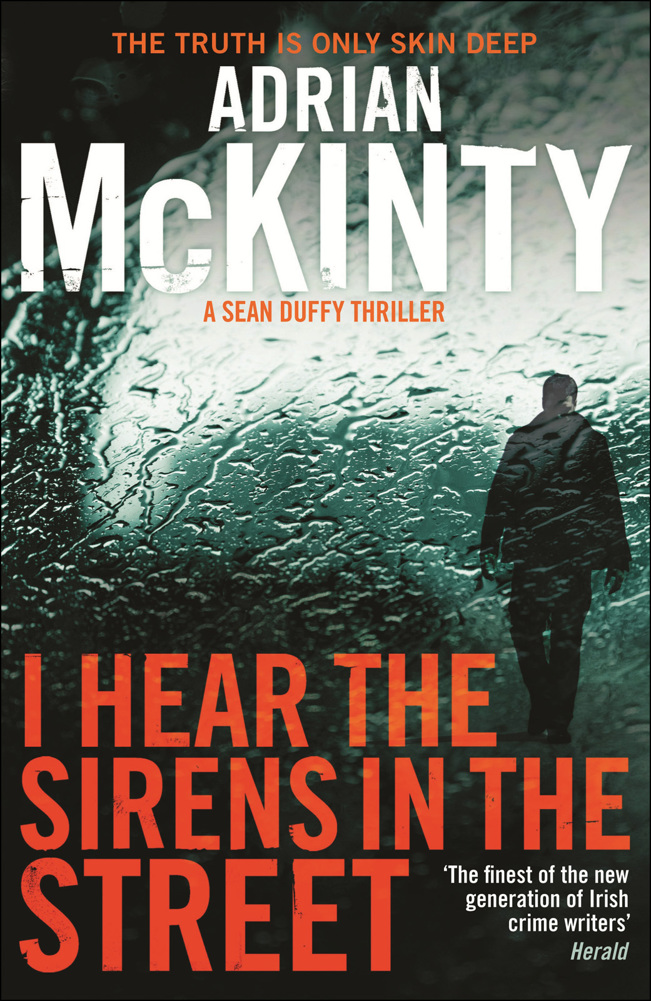

I Hear the Sirens in the Street

tomato plant.”

“Are you sure?”

“The lads were 100 per cent sure. A dead tomato plant. Nothing else.”

“No rosary pea or indeed anything weird?”

“No.”

“Shit.”

“Sorry, boss.”

“Thanks, Matty.”

No rosary pea. No Abrin.

“Do you want to go next door to the pub?” I ask him.

“Is that an order?”

“No.”

“Well, in that case I’d rather not, if you don’t mind.”

“All right, I’ll catch you another time. I’ll go myself.”

I juke next door and order a pint of Guinness and a double Scotch. A redhead called Kerry asks me if I will buy her a drink. She drinks a blackcurrant snakebite, which apparently is equal parts lager and cider with a dash of blackcurrant in a pint glass. After two she’s toast. I tell her the joke about the monkey and the pianist in the bar. She thinks it’s hilarious. She asks what I do for a living and I let slip that I’m a copper … And that, my friend, is it. She’s either Catholic or has your bog standard hatred of the police. When I come back from the toilet she’s gone. She’s beenthrough my wallet, but she’s only taken a twenty-pound note to get a taxi, which, when you think about it, isn’t so bad.

I order a double Bush for the road, hit it and walk back through the rain.

My head’s splitting. I stop to urinate outside the Presbyterian Church and an old lady walking her mutt tells me that I’m a sorry excuse for a human being. “I agree with you, love,” I say but when I turn round to make the argument there’s no one there at all.

12: A MESSAGE

A week went by without any developments. Like the majority of murder cases in Northern Ireland this one was starting to die. No new information from America. No eyewitness testimony. No calls on the Confidential Telephone. Mr O’Rourke had last been seen in Dunmurry. He’d got some Irish money, checked out of his crummy B&B and then he’d turned up dead. In another week or so the Chief would tell me to put the O’Rourke case on the back burner. A week after that, we’d move it to the yellow folders: open but not actively pursuing …

It was a Wednesday. The rain was hard and cold and coming at a forty-five-degree angle from the mountains. The sound of shotguns somewhere up country woke me at seven. I listened for a moment or two but there was no return fire and it was probably just a farmer going after foxes.

I put on the radio.

The local news was bad. An army base in Lurgan had been attacked with mortars, a firebomb had destroyed a bus depot in Armagh and an off-duty police reservist had been shot dead at the wheel of his tractor in Fermanagh.

The national news was about the Falklands War. Ships were still sailing south, the Pope wanted a peaceful resolution, the Americans were doing something, the EEC was calling for sanctions against Argentina.

I lay under the sheets for a while and finally wrapped myselfin the duvet and dragged my ass downstairs.

I called my mother. She said she was just going off to play bridge. Dad was also on his way out, going birding up the Giant’s Causeway.

“What do you see up there?” I asked, faking interest.

“Buzzards, kestrels, peregrines, sparrowhawks, gannets, occasional black and common guillemots, razorbills, eider ducks, purple sandpipers, colonies of fulmar, kittiwakes, Manx shear-waters, puffins, twites.”

“You’re making half those up.”

“I am not.”

“There’s no such bird as a fulmar or a twite. I wasn’t born yesterday.”

“Fulmar from the Norse ‘full’, meaning foul, ‘mar’ meaning gull, ‘fulmar’, because of their oily bills. They’re a type of seagull. Highly pelagic birds …”

“Which means?”

“They spend most of their life out at sea, like albatrosses.”

“And a twite?”

“A small passerine bird in the finch family.”

We both knew that I didn’t know what a passerine bird was, but an explanation would weary me. “I have to go, Dad.”

“Okay, son, see you, take care of yourself.”

“I will.”

I hung up and put on Radio Albania to get a Maoist version of the world news. I put Veda bread in the toaster and made a Nescafé. I ate the toast at the kitchen table and thought about my folks. They’d never spoken about why they’d only ever had one kid. I hadn’t been deprived of love, but I’d just never really connected with either of them. Dad was into fishing, bird watching, hare coursing, fell walking, hiking, that kind of thing, and as a wean I’d thought

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher