![Lamb: the Gospel According to Biff, Christ's Childhood Pal]()

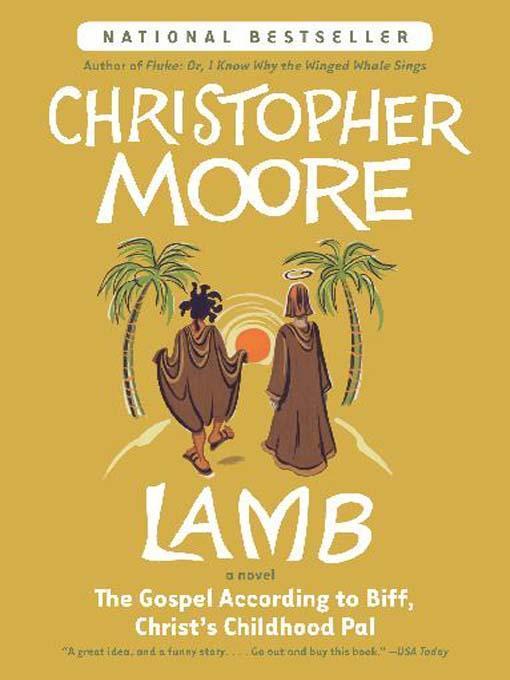

Lamb: the Gospel According to Biff, Christ's Childhood Pal

on me, Rumi. For six years I lived in a Buddhist monastery where the only female company was a wild yak. I know from desperate.”

Joshua grabbed my arm. “You didn’t?”

“Relax, I’m just making a point. You’re the Messiah here, Josh. What do you think?”

“I think we need to go to Tamil and find the third magus.” He set Vitra down and Rumi quickly pulled up his loincloth as the child ran to him. “Go with God, Rumi,” Joshua said.

“May Shiva watch over you, you heretics. Thank you for returning my daughter.”

Joshua and I gathered up our clothes and satchels, then bought some rice in the market and set out for Tamil. We followed the Ganges south until we came to the sea, where Joshua and I washed the gore of Kali from our bodies.

We sat on the beach, letting the sun dry our skin as we picked pitch out of our chest hairs.

“You know, Josh,” I said, as I fought a particularly stubborn gob of tar that had stuck in my armpit, “when you were leading those kids out of the temple square, and they were so little and weak, but none of them seemed afraid…well, it was sort of heartwarming.”

“Yep, I love all the little children of the world, you know?” “Really?”

He nodded. “Green and yellow, black and white.”

“Good to know—Wait, green?”

“No, not green. I was just fuckin’ with you.”

C hapter 22

Tamil, as it turned out, was not a small town in southern India, but the whole southern peninsula, an area about five times the size of Israel, so looking for Melchior was akin to walking into Jerusalem on any given day and saying, “Hey, I’m looking for a Jewish guy, anyone seen him?” What we had going for us was that we knew Melchior’s occupation, he was an ascetic holy man who lived a nearly solitary life somewhere along the coast and that he, like his brother Gaspar, had been the son of a prince. We found hundreds of different holy men, or yogis, most of them living in complete austerity in the forest or in caves, and usually they had twisted their bodies into some impossible posture. The first of these I saw was a yogi who lived in a lean-to on the side of a hill overlooking a small fishing village. He had his feet tucked behind his shoulders and his head seemed to be coming from the wrong end of his torso.

“Josh, look! That guy is trying to lick his own balls! Just like Bartholomew, the village idiot. These are my people, Josh. These are my people. I have found home.”

Well, I hadn’t really found home. The guy was just performing some sort of spiritual discipline (that’s what “yoga” means in Sanskrit: discipline) and he wouldn’t teach me because my intentions weren’t pure or some claptrap. And he wasn’t Melchior. It took six months and the last of our money and we both saw our twenty-fifth birthdays before we found Melchior reclining in a shallow stone nook in a cliff over the ocean. Seagulls were nesting at his feet.

He was a hairier version of his brother, which is to say he was slight, about sixty years old, and he wore a caste mark on his forehead. His hair and beard were long and white, shot with only a few stripes of black, and he had intense dark eyes that seemed to show no white at all. He wore only a loincloth and he was as thin as any of the Untouchables we had met in Kalighat.

Joshua and I clung to the side of the cliff while the guru untied from the human knot he’d gotten himself into. It was a slow process and we pretended to look at the seagulls and enjoy the view so as not to embarrass the holy man by seeming impatient. When he finally achieved a posture that did not appear as if it had been caused by being run over by an ox cart, Joshua said, “We’ve come from Israel. We were six years with your brother Gaspar in the monastery. I am—”

“I know who you are,” said Melchior. His voice was melodic, and every sentence he spoke seemed as if he were beginning to recite a poem. “I recognize you from when I first saw you in Bethlehem.”

“You do?”

“A man’s self does not change, only his body. I see you grew out of the swaddling clothes.”

“Yes, some time ago.”

“Not sleeping in that manger anymore?”

“No.”

“Some days I could go for a nice manger, some straw, maybe a blanket. Not that I need any of those luxuries, nor does anyone who is on the spiritual path, but still.”

“I’ve come to learn from you,” Joshua said. “I am to be a bodhisattva to my people and I’m not sure how to go

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher