![Lamb: the Gospel According to Biff, Christ's Childhood Pal]()

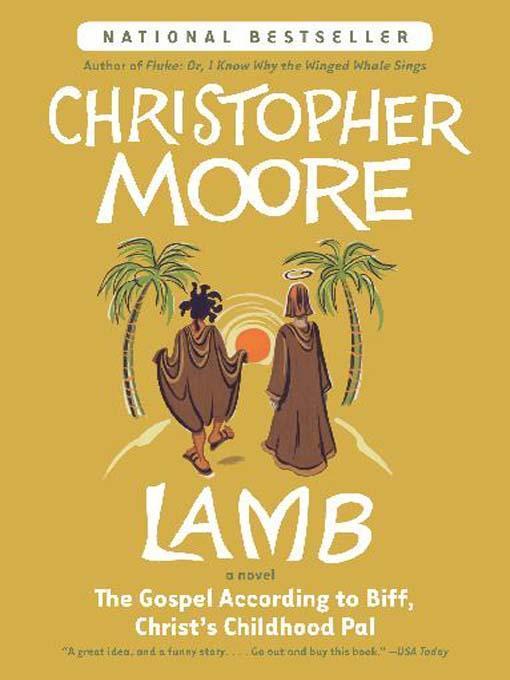

Lamb: the Gospel According to Biff, Christ's Childhood Pal

about it.”

“He’s the Messiah,” I said helpfully. “You know, the Messiah. You know, Son of God .”

“Yeah, Son of God ,” Joshua said.

“Yeah,” I said.

“Yeah,” said Joshua.

“So what do you have for us?” I asked.

“And who are you?”

“Biff,” I said.

“My friend,” said Josh.

“Yeah, his friend,” said I.

“And what do you seek?”

“Actually, I’d like to not have to hang on to this cliff a lot longer, my fingers are going numb.”

“Yeah,” said Josh.

“Yeah,” said I.

“Find yourself a couple of nooks on the cliff. There are several empty. Yogis Ramata and Mahara recently moved on to their next rebirth.”

“If you know where we can find some food we would be grateful,” Joshua said. “It’s been a long time since we’ve eaten. And we have no money.”

“Time then for your first lesson, young Messiah. I am hungry as well. Bring me a grain of rice.”

Joshua and I climbed across the cliff until we found two nooks, tiny caves really, that were close to each other and not so far above the beach that falling out would kill us. Each of our nooks had been gouged out of the solid rock and was just wide enough to lie down in, tall enough to sit up in, and deep enough to keep the rain off if it was falling straight down. Once we were settled, I dug through my satchel until I found three old grains of rice that had worked their way into a seam. I put them in my bowl, then carried the bowl in my teeth as I made my way back to Melchior’s nook.

“I did not ask for a bowl,” said Melchior. Joshua had already skirted the cliff and was sitting next to the yogi with his feet dangling over the edge. There was a seagull in his lap.

“Presentation is half the meal,” I said, quoting something Joy had once said.

Melchior sniffed at the rice grains, then picked one up and held it between his bony fingertips.

“It’s raw.”

“Yes, it is.”

“We can’t eat it raw.”

“Well, I would have served it up steaming with a grain of salt and a molecule of green onion if I’d known you wanted it that way.” (Yeah, we had molecules in those days. Back off.)

“Very well, this will have to do.” The holy man held the bowl with the rice grains in his lap, then closed his eyes. His breathing began to slow, and after a moment he appeared not to be breathing at all.

Josh and I waited. And looked at each other. And Melchior didn’t move. His skeletal chest did not rise with breath. I was hungry and tired, but I waited. And the holy man didn’t move for almost an hour. Considering the recent nook vacancies on the cliff face, I was a little concerned that Melchior might have succumbed to some virulent yogi-killing epidemic.

“He dead?” I asked.

“Can’t tell.”

“Poke him.”

“No, he’s my teacher, a holy man. I’m not poking him.”

“He’s Untouchable.”

Joshua couldn’t resist the irony, he poked him. Instantly the yogi opened his eyes, pointed out to sea and screamed, “Look, a seagull!”

We looked. When we looked back the yogi was holding a full bowl of rice. “Here, go cook this.”

So began Joshua’s training to find what Melchior called the Divine Spark. The holy man was stern with me, but his patience with Joshua was infinite, and it was soon evident that by trying to be part of Joshua’s training I was actually holding him back. So on our third morning living in the cliff, I took a long satisfying whiz over the side (and is there anything so satisfying as whizzing from a high place?) then climbed to the beach and headed into the nearest town to look for a job. Even if Melchior could make a meal out of three grains of rice, I’d scraped all the stray grains out of both my and Joshua’s satchels. The yogi might be able to teach a guy to twist up and lick his own balls, but I couldn’t see that there was much nourishment in it.

The name of the town was Nicobar, and it was about twice the size of Sepphoris in my homeland, perhaps twenty thousand people, most of whom seemed to make their living from the sea, either as fishermen, traders, or shipbuilders. After inquiring at only a few places, I realized that for once it wasn’t my lack of skills that were keeping me from making a living, it was the caste system. It extended far deeper into the society than Rumi had told me. Subcastes of the larger four dictated that if you were born a stonecutter, your sons would be stonecutters, and their sons after them, and you were bound by

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher