![Murder most holy]()

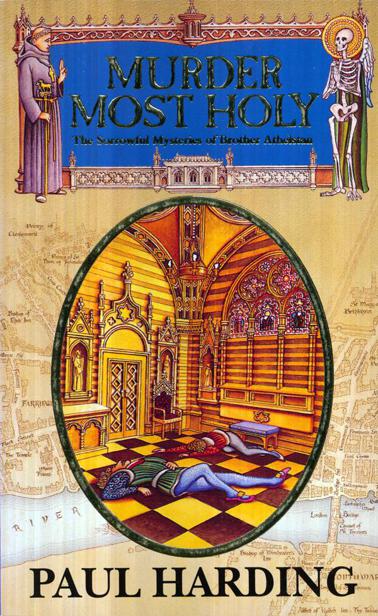

Murder most holy

Benedicta and her worries about her husband; the skeleton in the church; and Father Prior wanting his help. He glanced up at Cranston .

‘Murder follows me always,’ he whispered, ‘dragging behind me like some hell-sent beast. I made one mistake, Sir John, and how I have paid for it!’

Cranston rose and stood over him, patting him gently on the shoulder.

‘You did no wrong, Athelstan,’ he said quietly. ‘You were a young man who went to war. You took your younger brother with you. It was God’s will he died. If there was a price to pay, you have done so. Now there’s another Francis — my son, your godson. Life goes on, Brother. I will see you on Wednesday.’

Cranston opened the door and slipped out into the dusk.

Athelstan sat listening to him leave. He went and stood at the window, staring up at the top of the darkening tower of St Erconwald ’s. He breathed deeply, trying to cleanse his mind. Father Prior would have to wait and so would that skeleton in the church. He would not study the stars tonight but instead analyse the problem Cranston had brought.

He went back to sit at the table and studied the manuscript Cranston had left. How could men be killed so subtly in that scarlet chamber? ‘No food,’ he whispered to himself. ‘No drink, no trap doors or hidden devices. No silent assassin. So how did those men die?’

Athelstan’s mind raced through every possibility but the deaths were so apparently simple — there was no clue, no hook to hang a suspicion on, not a crack to prise open. Athelstan’s eyes closed. He woke with a start. The candle had burned low. Somehow, he concluded, the key to all the deaths lay in the last two. How had an archer become so terrified he’d shot his companion?

Athelstan’s head sank again and he drifted into a deep dream: he sat in a scarlet chamber where the figure of death with its skeletal face performed a strange dance, whilst some silent force crept slowly and menacingly towards him...

Athelstan awoke stiff and cold the next morning, still sitting at the table, his head on his arms, Bonaventure brushing urgently against him. Somewhere amongst the squalid huts and tenements of Southwark a cockerel crowed its morning hymn to the sun. The priest rose and stretched, rubbing his face and wishing he had gone to bed. He folded up the piece of parchment Cranston had given him and took it up to the chest in his small bedroom. He then stripped, washing his body with a wet rag, shaved, and tried to concentrate on the mass he was about to celebrate. He must not think about the distractions milling in his mind. He cleaned his teeth with a mixture of salt and vinegar, took out his second robe, broke his fast on some stale bread and absent-mindedly fed Bonaventure who had apparently spent the night touring his small kingdom of alleys around the church.

‘Something tells me, Bonaventure,’ Athelstan said quietly as he crouched to feed the battered tom cat, ‘that this is going to be a strange day.’

He went across and celebrated a private mass on a makeshift altar in the middle of the nave, deliberately not looking at the coffin on his left with its grisly contents. No one else came except Pernel the Fleming and she seemed more interested in the coffin than anything else. Athelstan finished the mass, clearing the altar in preparation for the return of the workmen. He fed Philomel, hobbling his war horse in the small yard to give it some exercise, and returned to his house. He decided to concentrate on drawing up the list of supplies he needed before going back to the crude sketches of how he wished the new sanctuary to look. However, he still felt both hungry and restless so, locking his house, went down to a cookshop in Blowbladder Alley.

He bought a crisp meat pie and a dish of vegetables covered with gravy and sat outside, his back to the wall, enjoying the hot juices and savoury smell. A beggar, his nose slit for some previous crime, came crawling up, whining for alms. Athelstan gave him two pennies. The fellow disappeared into the cookshop to buy pies from the fat dumpling of a baker and rejoined Athelstan. After half an hour the priest got tired of the fellow’s rambling tales about his exploits as a soldier and decided to go for a walk.

He always liked Southwark first thing in the morning, despite the over-full sewers, the putrid mounds of refuse and the denizens of its underworld, now sliding back to their garrets to await the return of night. A

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher