![No Mark Upon Her]()

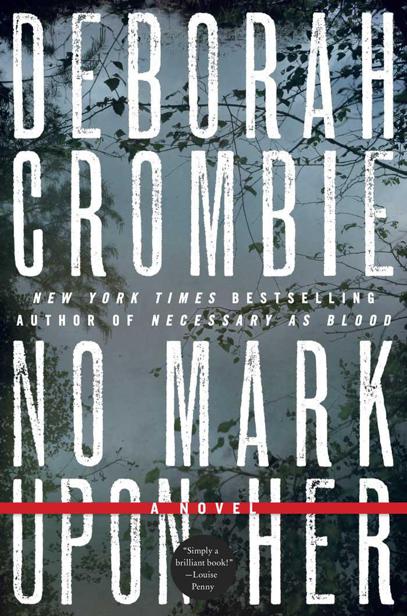

No Mark Upon Her

make his hand obey, he had no command over his knees. When they threatened to buckle, he staggered two steps to the wall and slid down with his back against it. He felt as if the very air were a massive weight, pressing him down, squeezing his lungs. Finn nuzzled him and climbed half into his lap, and as he wrapped his arms round the dog, he couldn’t tell which of them whimpered. “Sorry, boy, sorry,” he whispered. “It’ll be okay. We’ll be okay. It’s just a little rain.”

He repeated to himself the rational explanation for his physical distress. Damage to middle ear, due to shelling. Swift changes in barometric pressure may affect equilibrium. It was a familiar mantra.

The army doctors had told him that, as if he hadn’t known it himself. They’d also told him that he’d been heavily concussed, and that he’d suffered some loss of hearing. “Not enough,” he said aloud, and cackled a little wildly at his own humor. Finn licked his chin and Kieran hugged him harder. “It will pass,” he whispered, meaning to reassure them both.

The room reeled, bringing a wave of nausea so intense he had to swallow against it. That, too, was related to his middle ear, or so they’d told him. An inconvenience, they’d said. He slid a little farther down the wall, and Finn shifted the rest of his eighty-pound weight into his lap.

So inconvenient, along with the shakes and the sweats and the screaming in his sleep, that they’d discharged him. Bye-bye, Kieran Connolly, Combat Medical Technician, Class 1, and here’s your bit of decoration and your nice pension. He’d used the pension to buy the boatshed.

He’d rowed at Henley in his teens, crewing for a London club. To a kid from Tottenham who’d stumbled across the Lea Rowing Club quite by accident, Henley had seemed like paradise.

It was just him and his dad, then. His mum had scarpered when he was a baby, but it was not something his dad ever talked about. They’d lived in a terraced street that had hung on to respectability by a thread, his dad repairing and building furniture in the shop below the flat. Kieran, white and Irish in a part of north London where that made him a minority, had been well on his way to life as a petty thug.

Kieran stroked Finn’s warm muzzle and closed his eyes, trying to use the memory to quell the panic, the way the army therapist had taught him.

It had been hot, that long ago Saturday in June, just after his fourteenth birthday. He’d stolen a bike on a dare, ridden it in a wild, heart-hammering escape through the streets of Tottenham to the path that ran down along the River Lea. And then, with the trail clear behind him, his legs burning and the sun beating down on his head, he’d seen the single shells on the water.

The sound of the storm faded from his consciousness as the memory drew him in.

He’d stopped, gazing at the water, all thought of pursuit and punishment gone in an instant. The boats were stillness in motion, graceful as dragonflies, skimming the surface of the mercury-gleaming river, and the sight had gripped and squeezed something inside him that he hadn’t known existed.

All that afternoon, he’d watched, and in the dimness of the evening, he’d pedaled slowly back to Tottenham and returned the bike, ignoring the taunts of his mates. The next Saturday he’d gone back to the river, drawn by something he couldn’t articulate, a longing that until then had only teased the feathery edges of his imagination.

Another Saturday, and another. He learned that the boat place was called the Lea Rowing Club. He began to name the boats; singles, doubles, pairs, quads, fours, and the eights—if the singles had made him think of dragonflies, the eights were giant insects, moving in a rhythm that seemed both alien and familiar and that made him think of the pictures of Roman galleys he’d seen in school history books.

And they talked to him, the oarsmen, when they noticed him hanging about. He was tall, even then. Awkward, scrawny, black-haired, pale-skinned even at summer’s height—all in all, not a very prepossessing specimen. But although he hadn’t realized it then, his inches had made him rowing material, and they’d been assessing his potential.

After a bit, they’d let him help load the boats onto the trailers or lift them back onto the trestles that waited in the boatyard like cradles. One day a man tossed him a cloth and nodded at a dripping single. “Wipe it down, if you want,”

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher