![Pnin]()

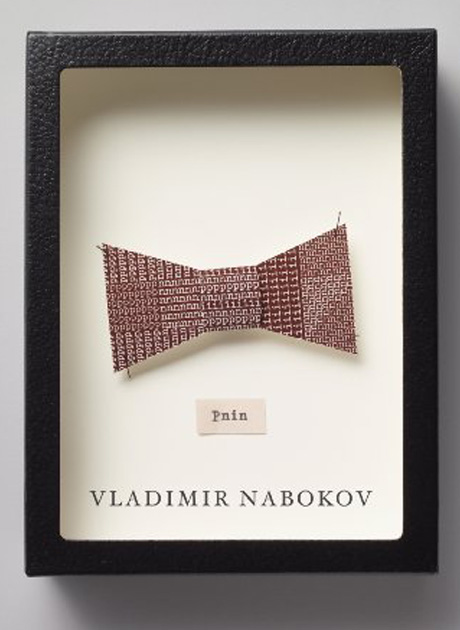

Pnin

rocket of an asterisk, the flare of a 'sic!' This line of land was to be shunned as the doom of everything that determined the rapture of endless approximation. Index cards were gradually loading a shoe box with their compact weight. The collation of two legends; a precious detail in manners or dress; a reference checked and found to be falsified by incompetence, carelessness, or fraud; the spine thrill of a felicitous guess; and all the innumerable triumphs of bezkorïstnïy (disinterested, devoted) scholarship - this had corrupted Pnin, this had made of him a happy, footnote-drugged maniac who disturbs the book mites in a dull volume, a foot thick, to find in it a reference to an even duller one. And on another, more human, plane there was the little brick house that he had rented on Todd Road, at the corner of Cliff Avenue.

It had lodged the family of the late Martin Sheppard, an uncle of Pnin's previous landlord in Creek Street and for many years the caretaker of the Todd property, which the town of Waindell had now acquired for the purpose of turning its rambling mansion into a modern nursing home. Ivy and spruce muffled its locked gate, whose top Pnin could see on the far side of Cliff Avenue from a north window of his new home. This avenue was the crossbar of a T, in the left crotch of which he dwelt. Opposite the front of his house, immediately across Todd Road (the upright of the T), old elms screened the sandy shoulder of its patched-up asphalt from a cornfield east of it, while along its west side a regiment of young fir trees, identical upstarts, walked, campusward, behind a fence, for almost the whole distance to the next residence - the Varsity Football Coach's magnified cigar box; which stood half a mile south from Pnin's house.

The sense of living in a discrete building all by himself was to Pnin something singularly delightful and amazingly satisfying to a weary old want of his innermost self, battered and stunned by thirty-five years of homelessness. One of the sweetest things about the place was the silence - angelic, rural, and perfectly secure, thus in blissful contrast to the persistent cacophonies that had surrounded him from six sides in the rented rooms of his former habitations. And the tiny house was so spacious! With grateful surprise, Pnin thought that had there been no Russian Revolution, no exodus, no expatriation in France, no naturalization in America, everything - at the best, at the best, Timofey! - would have been much the same: a professorship in Kharkov or Kazan, a suburban house such as this, old books within, late blooms without. It was - to be more precise - a two-storey house of cherry-red brick, with white shutters and a shingle roof. The green plat on which it stood had a frontage of about fifty arshins and was limited at the back by a vertical stretch of mossy cliff with tawny shrubs on its crest. A rudimentary driveway along the south side of the house led to a small whitewashed garage for the poor man's car Pnin owned. A curious basketlike net, somewhat like a glorified billiard pocket - lacking, however, a bottom - was suspended for some reason above the garage door, upon the white of which it cast a shadow as distinct as its own weave but larger and in a bluer tone. Pheasants visited the weedy ground between the garden and the cliff. Lilacs - those Russian garden graces, to whose spring-time splendour, all honey and hum, my poor Pnin greatly looked forward - crowded in sapless ranks along one wall of the house. And a tall deciduous tree, which Pnin, a birch-lime-willow-aspen-poplar-oak man, was unable to identify, cast its large, heart-shaped, rust-coloured leaves and Indian-summer shadows upon the wooden steps of the open porch.

A cranky-looking oil furnace in the basement did its best to send up its weak warm breath through registers in the floors. The kitchen looked healthy and gay, and Pnin had a great time with all kinds of cookware, kettles and pans, toasters and skillets, all of which came with the house. The living-room was scantily and dingily furnished, but had a rather attractive bay harbouring a huge old globe, where Russia was painted a pale blue, with a discoloured or scrubbled patch all over Poland. In a very small dining-room, where Pnin contemplated arranging a buffet supper for his guests, a pair of crystal candlesticks with pendants was responsible in the early mornings for iridescent reflections, which glowed charmingly on the sideboard and

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher