![Pnin]()

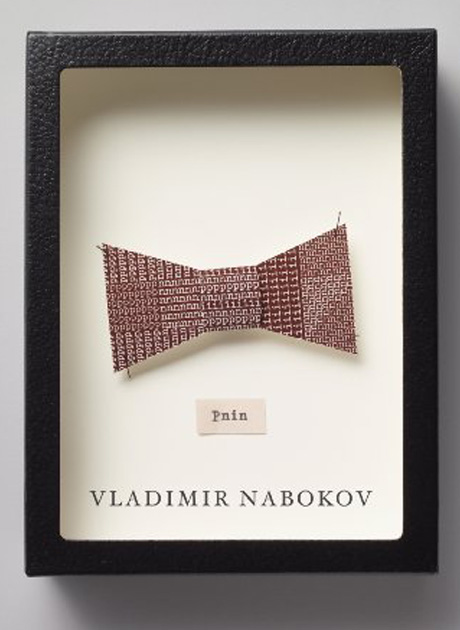

Pnin

with great thrusts of healthy lodge humour any attempt to inveigle him into the subtleties of the parley-voo. A highly esteemed money-getter, he had recently induced a rich old man, whom three great universities had courted in vain, to promote with a fantastic endowment a riot of research conducted by graduates under the direction of Dr Slavski, a Canadian, toward the erection, on a hill near Waindell, of a 'French Village', two streets and a square, to be copied from those of the ancient little burg of Vandel in the Dordogne. Despite the grandiose element always present in his administrative illuminations, Blorenge personally was a man of ascetic tastes. He had happened to go to school with Sam Poore, Waindell's President, and for many years, regularly, even after the latter had lost his sight, the two would go fishing together on a bleak, wind-raked lake, at the end of a gravel road lined with fireweed, seventy miles north of Waindell, in the kind of dreary brush country - scrub oak and nursery pine - that, in terms of Nature, is the counterpart of a slum. His wife, a sweet woman of simple antecedents, referred to him at her club as 'Professor Blorenge'. He gave a course entitled 'Great Frenchmen', which he had had his secretary copy out from a set of The Hastings Historical and Philosophical Magazine for 1882-94, discovered by him in an attic and not represented in the College Library.

3

Pnin had just rented a small house, and had invited the Hagens and the Clementses, and the Thayers, and Betty Bliss to a house-warming party. On the morning of that day, good Dr Hagen made a desperate visit to Blorenge's office and revealed to him, and to him alone, the whole situation. When he told Blorenge that Falternfels was a strong anti-Pninist, Blorenge dryly rejoined that so was he; in fact, after meeting Pnin socially, he 'definitely felt' (it is truly a wonder how prone these practical people are to feel rather than to think) that Pnin was not fit even to loiter in the vicinity of an American college. Staunch Hagen said that for several terms Pnin had been admirably dealing with the Romantic Movement and might surely handle Chateaubriand and Victor Hugo under the auspices of the French Department.

'Dr Slavski takes care of that crowd,' said Blorenge. 'In fact, I sometimes think we overdo literature. Look, this week Miss Mopsuestia begins the Existentialists, your man Bodo does Romain Rolland, I lecture on General Boulanger and De Béranger. No, we have definitely enough of the stuff.'

Hagen, playing his last card, suggested Pnin could teach a French Language course: like many Russians, our friend had had a French governess as a child, and after the Revolution he lived in Paris for more than fifteen years.

'You mean,' asked Blorenge sternly, 'he can speak French?'

Hagen, who was well aware of Blorenge's special requirements, hesitated.

'Out with it, Herman! Yes or no?'

'I am sure he could adapt himself.'

'He does speak it, eh?'

'Well, yes.'

'In that case,' said Blorenge, 'we can't use him in First-Year French. It would be unfair to our Mr Smith, who gives the elementary course this term and, naturally, is required to be only one lesson ahead of his students. Now it so happens that Mr Hashimoto needs an assistant for his overflowing group in Intermediate French. Does your man read French as well as speak it?'

'I repeat, he can adapt himself,' hedged Hagen.

'I know what adaptation means,' said Blorenge, frowning. 'In 1950, when Hash was away, I engaged that Swiss skiing instructor and he smuggled in mimeo copies of some old French anthology. It took us almost a year to bring the class back to its initial level. Now, if what's-his-name does not read French -'

'I'm afraid he does,' said Hagen with a sigh.

'Then we can't use him at all. As you know, we believe only in speech records and other mechanical devices. No books are allowed.'

'There still remains Advanced French,' murmured Hagen.

'Carolina Slavski and I take care of that,' answered Blorenge.

4

For Pnin, who was totally unaware of his protector's woes, the new Fall Term began particularly well: he had never had so few students to bother about, or so much time for his own research. This research had long entered the charmed stage when the quest overrides the goal, and a new organism is formed, the parasite so to speak of the ripening fruit. Pnin averted his mental gaze from the end of his work, which was so clearly in sight that one could make out the

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher