![Pnin]()

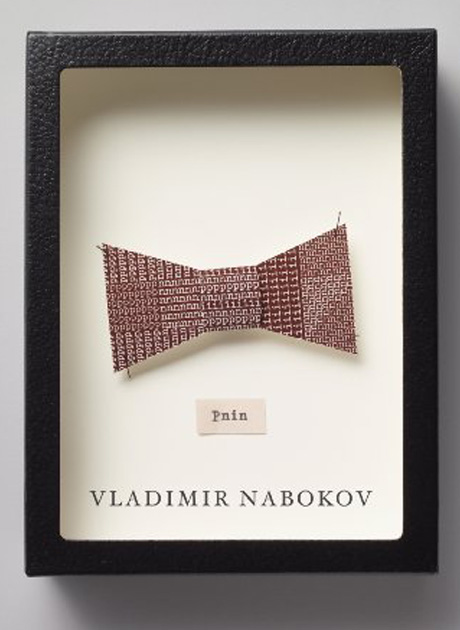

Pnin

Whom does he remind me of? thought Pnin suddenly. Eric Wind? Why? They are quite different physically.

11

The setting of the final scene was the hallway. Hagen could not find the cane he had come with (it had fallen behind a trunk in the closet).

'And I think I left my purse where I was sitting,' said Mrs Thayer, pushing her pensive husband ever so slightly toward the living-room.

Pnin and Clements, in last-minute discourse, stood on either side of the living-room doorway, like two well-fed caryatides, and drew in their abdomens to let the silent Thayer pass. In the middle of the room Professor Thomas and Miss Bliss - he with his hands behind his back and rising up every now and then on his toes, she holding a tray - were standing and talking of Cuba, where a cousin of Betty's fiancé had lived for quite a while, Betty understood. Thayer blundered from chair to chair, and found himself with a white bag, not knowing really where he picked it up, his mind being occupied by the adumbrations of lines he was to write down later in the night:

We sat and drank, each with a separate past locked up in him, and fate's alarm clocks set at unrelated futures - when, at last, a wrist was cocked, and eyes of consorts met...

Meanwhile, Pnin asked Joan Clements and Margaret Thayer if they would care to see how he had embellished the upstairs rooms. The idea enchanted them. He led the way. His so-called kabinet now looked very cosy, its scratched floor snugly covered with the more or less Pakistan rug which he had once acquired for his office and had recently removed in drastic silence from under the feet of the surprised Falternfels. A tartan lap robe, under which Pnin had crossed the ocean from Europe in 1940, and some endemic cushions disguised the unremovable bed. The pink shelves, which he had found supporting several generations of children's books - from Tom the Bootblack, or the Road to Success by Horatio Alger, Jr, 1889, through Rolf in the Woods by Ernest Thompson Seton, 1911, to a 1928 edition of Compton's Pictured Encyclopedia in ten volumes with foggy little photographs - were now loaded with three hundred sixty-five items from the Waindell College Library.

'And to think I have stamped all these,' sighed Mrs Thayer, rolling her eyes in mock dismay.

'Some stamped Mrs Miller,' said Pnin, a stickler for historical truth.

What struck the visitors most in the bedroom was a large folding screen that cut off the four-poster bed from insidious draughts, and the view from the row of small windows: a dark rock wall rising abruptly some fifty feet away, with a stretch of pale starry sky above the black growth of its crest. On the back lawn, across the reflection of a window, Laurence strolled into the shadows.

'At last you are really comfortable,' said Joan.

'And you know what I will say to you,' replied Pnin in a confidential undertone vibrating with triumph. 'Tomorrow morning, under the curtain of mysteree, I will see a gentleman who is wanting to help me to buy this house!'

They came down again. Roy handed his wife Betty's bag. Herman found his cane. Margaret's bag was sought. Laurence reappeared.

'Good-bye, good-bye, Professor Vin!' sang out Pnin, his cheeks ruddy and round in the lamplight of the porch.

(Still in the hallway, Betty and Margaret Thayer admired proud Dr Hagen's walking-stick, recently sent him from Germany, a gnarled cudgel, with a donkey's head for knob. The head could move one ear. The cane had belonged to Dr Hagen's Bavarian grandfather, a country clergyman. The mechanism of the other ear had broken down in 1914, according to a note the pastor had left. Hagen carried it, he said, in defence against a certain Alsatian in Greenlawn Lane. American dogs were not used to pedestrians. He always preferred walking to driving. The ear could not be repaired. At least, in Waindell.)

'Now I wonder why he called me that,' said T.W. Thomas, Professor of Anthropology, to Laurence and Joan Clements as they walked through blue darkness toward four cars parked under the elms on the other side of the road.

'Our friend,' answered Clements, 'employs a nomenclature all his own. His verbal vagaries add a new thrill to life. His mispronunciations are mythopeic. His slips of the tongue are oracular. He calls my wife John.'

'Still I find it a little disturbing,' said Thomas.

'He probably mistook you for somebody else,' said Clements. 'And for all I know you may be somebody else.'

Before they had crossed the street

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher