![Pnin]()

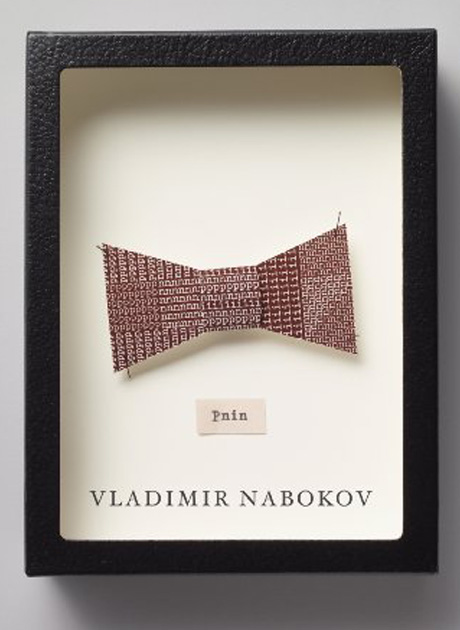

Pnin

devise, and it was always a pleasure to watch good old bald Tim Pnin bend slightly to touch with his lips the light hand that Joan, alone of all the Waindell ladies, knew how to raise to exactly the right level for a Russian gentleman to kiss. Laurence, fatter than ever, dressed in nice grey flannels, sank into the easy chair and immediately grabbed the first book at hand, which happened to be an English-Russian and Russian-English pocket dictionary. Holding his glasses in one hand, he looked away, trying to recall something he had always wished to check but now could not remember, and his attitude accentuated his striking resemblance, somewhat en jeune, to Jan van Eyck's ample-jowled, fluff-haloed Canon van der Paele, seized by a fit of abstraction in the presence of the puzzled Virgin to whom a super, rigged up as St George, is directing the good Canon's attention. Everything was there - the knotty temple, the sad, musing gaze, the folds and furrows of facial flesh, the thin lips, and even the wart on the left cheek.

Hardly had the Clementses settled down than Betty let in the man interested in bird-shaped cakes. Pnin was about to say 'Professor Vin' but Joan - rather unfortunately, perhaps - interrupted the introduction with 'Oh, we know Thomas! Who does not know Tom?' Tim Pnin returned to the kitchen, and Betty handed around some Bulgarian cigarettes.

'I thought, Thomas,' remarked Clements, crossing his fat legs, 'you were out in Havana interviewing palm-climbing fishermen?'

'Well, I'll be on my way after mid years,' said Professor Thomas. 'Of course, most of the actual field work has been done already by others.'

'Still, it was nice to get that grant, wasn't it?'

'In our branch,' replied Thomas with perfect composure, 'we have to undertake many difficult journeys. In fact, I may push on to the Windward Islands. If,' he added with a hollow laugh, 'Senator McCarthy does not crack down on foreign travel.'

'He received a grant of ten thousand dollars,' said Joan to Betty, whose face dropped a curtsy as she made that special grimace consisting of a slow half-bow and tensing of chin and lower lip that automatically conveys, on the part of Bettys, a respectful, congratulatory, and slightly awed recognition of such grand things as dining with one's boss, being in Who's Who, or meeting a duchess.

The Thayers, who came in a new station wagon, presented their host with an elegant box of mints, Dr Hagen, who came on foot, triumphantly held aloft a bottle of vodka.

'Good evening, good evening, good evening,' said hearty Hagen.

'Dr Hagen,' said Thomas as he shook hands with him. 'I hope the Senator did not see you walking about with that stuff.'

The good doctor had perceptibly aged since last year but was as sturdy and square-shaped as ever with his well-padded shoulders, square chin, square nostrils, leonine glabella, and rectangular brush of grizzled hair that had something topiary about it. He wore a black suit over a white nylon shirt, and a black tie with a red thunderbolt streaking down it. Mrs Hagen had been prevented from coming, at the very last moment, by a dreadful migraine, alas.

Pnin served the cocktails 'or better to say flamingo tails - specially for ornithologists', as he slyly quipped.

'Thank you!' chanted Mrs Thayer, as she received her glass, raising her linear eyebrows, on that bright note of genteel inquiry which is meant to combine the notions of surprise, unworthiness, and pleasure. An attractive, prim, pink-faced lady of forty or so, with pearly dentures and wavy goldenized hair, she was the provincial cousin of the smart, relaxed Joan Clements, who had been all over the world, even in Turkey and Egypt, and was married to the most original and least liked scholar on the Waindell campus. A good word should be also put in at this point for Margaret Thayer's husband, Roy, a mournful and mute member of the Department of English, which, except for its ebullient chairman, Cockerell, was an aerie of hypochondriacs. Outwardly, Roy was an obvious figure. If you drew a pair of old brown loafers, two beige elbow patches, a black pipe, and two baggy eyes under heavy eyebrows, the rest was easy to fill out. Somewhere in the middle distance hung an obscure liver ailment, and somewhere in the background there was Eighteenth-Century Poetry, Roy's particular field, an overgrazed pasture, with the trickle of a brook and a clump of initialled trees; a barbed-wire arrangement on either side of this field

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher