![Ptolemy's Gate]()

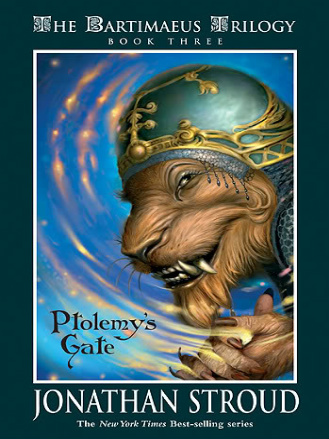

Ptolemy's Gate

had enough. He departed his office for the day.

For some years, ever since the affair of Gladstone's Staff, Mandrake had been a close associate of the playwright Mr. Quentin Makepeace. There was good reason to be so—above all things, the Prime Minister loved theater, and Mr. Makepeace consequently exerted great influence upon him. By pretending to share his leader's joy, Mandrake had managed to maintain a bond with Devereaux that other, more intolerant, members of the Council could only envy. But it came at a price: more than once Mandrake had found himself cajoled into appearing in dreadful amateur productions at Richmond, prancing about the stage in chiffon leggings or bulbous pantaloons, and—on one terrible never-to-be-forgotten occasion—swinging from a harness wearing wings of sparkly gauze. Mandrake had borne his colleagues' merriment stoically: Devereaux's goodwill mattered more.

In return for his support, Quentin Makepeace had frequently offered Mandrake counsel, and Mandrake had found him surprisingly astute, quick to pick up on interesting rumors, accurate in his predictions of the Prime Minister's fluctuating moods. Many times he had gained advantage by following the playwright's advice.

But in recent months, as his work commitments escalated, Mandrake had become weary of his companion and resentful of the time wasted nurturing Devereaux's enthusiasms. He had no time for trivialities. For weeks he had avoided accepting Makepeace's invitation to call. Now, dead-eyed and rudderless, he resisted no longer.

A servant let him into the quiet house. Mandrake crossed the hall, passing beneath pink-tinged chandeliers and a monumental oil of the playwright leaning in his satin dressing gown against a pile of self-penned works. Keeping his eyes averted (he always considered the gown a little short), Mandrake descended the central staircase. His shoes padded soundlessly on the thick pile carpet. The walls were hung with framed posters from theaters across the world. FIRST NIGHT! WORLD PREMIERE! MR. MAKEPEACE'S PLEASURE TO PRESENT! Silently a dozen adverts screamed their message down.

At the foot of the stairs a studded iron door led to the playwright's workroom.

Even as he knocked, the door was flung open. A broad and beaming face looked out. "John, my boy! Excellent! I am so pleased. Lock the door behind you. We shall have tea, with a twist of peppermint. You look as though you need reviving."

Mr. Makepeace was a whirl of little movements, precise, defined, balletic. His diminutive frame spun and bobbed, pouring the tea, sprinkling the peppermint, restless as a little bird. His face sparkled with vigor, his red hair shone; his smile twitched repeatedly as if reflecting on a secretive delight.

As usual, his clothes expressed his buoyant personality: tan shoes, a pair of pea-green trousers with maroon check, a bright yellow waistcoat, a pink cravat, a loose-fitting linen shirt with pleats upon the sleeves. Today, however, the sleeves were rolled up above the elbows, and cravat and waistcoat were concealed behind a stained white apron. Evidently Mr. Makepeace was hard at work.

With a tiny spoon he stirred the tea, tapped it twice upon the glass, and handed the result to Mandrake."There!" he cried. "Get that down you. Now, John"—his smile was tender, solicitous—"little birds tell me all is not well."

Briefly, without elaboration, Mandrake mentioned the events of the past few hours. The smaller man tutted and cooed with sympathy. "Disgraceful!" he cried at last. "And you were only doing your duty! But fools like Farrar are all too ready to tear you to pieces, first chance they get. You know what their problem is, John?" He gave a significant pause. "Envy. We are surrounded by envious minnows, who resent our talents. I get this reaction all the time in the theater, critics carping at my efforts-Mandrake grunted. "Well, you'll put them in their place again tomorrow," he said. "With the premiere."

"Indeed I shall, John, indeed I shall. But you know, sometimes government is so, so friendless. I expect you feel that, don't you? You feel as if you're on your own. But I am your friend, John, I respect you, even if no one else does."

"Thanks, Quentin. I'm not sure it's quite as bad as—"

"You see, you've got something they haven't. Know what it is? Vision. I've always seen that in you. You're clear-sighted. And ambitious too. I read that in you, yes I do."

Mandrake looked down at his tea, which he

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher