![Ptolemy's Gate]()

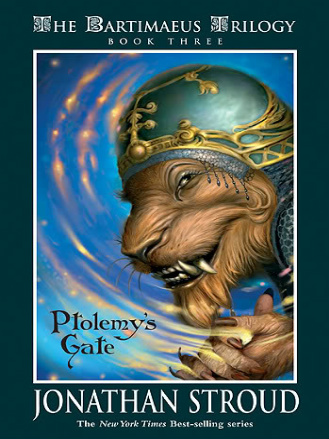

Ptolemy's Gate

followed after. We went in search of anchovy bread. When we returned, our quest fulfilled, the library precinct was quiet and still.

My master knew the incident was inauspicious, but his studies were his consuming interest, and he chose to ignore the implications. But I did not, and nor did the people of Alexandria. Rumors of the matter circulated swiftly, some more creative than accurate.[4] The king's son was unpopular; his humiliation was regarded with general hilarity and Ptolemy's celebrity grew.

[4] One account, daubed upon the harbor walls and illustrated by a lively sketch, described the king's son being bent bare-bottomed over a library table and spanked with a royal flail by demon or demons unknown.

By night I floated on the winds above the palace, conversing with the djinn.

"What news?"

"News, Bartimaeus, of the king's son. His brow is heavy with wrath and fear. He mutters daily that Ptolemy might send a demon to destroy him and seize the throne. The danger pulses in his temple like a beating drum."

"But my master lives only for his writing. He has no interest in the crown."

"Even so. The king's son chews on the problem late at night and over wine. He sends emissaries out in search of men that might aid him quash this threat."

"Affa, I thank you. Fly well."

"Fly well, Bartimaeus."

Ptolemy's cousin was a fool and a sot, but I understood his fears. He himself was not a magician. The magicians of Alexandria were ineffectual shadows of the great ones of the past, under whom I'd toiled.[5] The army was weaker than for generations, and mostly far away. In comparison, Ptolemy was powerful indeed. No question, the king's son would be vulnerable should my master decide to overthrow him.

[5] The ancient pharaohs had traditionally relied upon their priests for such services, and the Greek dynasty had seen no reason to alter this policy. But whereas in the past talented individuals had made their way to Egypt to ply their trade, allowing the Empire to grow strong on the backs of weeping djinn, that time had long since gone.

Time passed. I watched and waited.

The king's son found his men. Money was paid. One moonlit night four assassins stole into the palace gardens and paid a call upon my master. As I may have mentioned, their visit was of short duration.

The king's son had taken the precaution of being away from Alexandria that night; he was out in the desert hunting. When he returned, he was greeted first by a flock of carrion birds wheeling in the skies about the Crocodile Gate, then by the hanging corpses of three assassins. Their feet brushed against the plumes of his chariot as he passed into the city. Face mottled white and crimson, the prince retired to his chambers and was not seen for days.

"Master," I said. "Your life remains at risk. You must leave Alexandria."

"Quite impossible, Rekhyt, as you know. The Library is here."

"Your cousin is your implacable foe. He will try again."

"And you will be here to foil him, Rekhyt. I have every confidence in you."

"The assassins were but men. The next who come will not be human."

"I am sure you will cope. Do you have to squat so? It distresses me."

"I'm an imp today. Imps squat. Listen," I said, "your confidence in me is gratifying, but frankly I can do without it. Just as I can do without being in the firing line when a marid comes knocking on your door."

He chuckled into his goblet. "A marid! I think you overestimate the ability of our court magicians. A one-legged mouler I can believe."

"Your cousin casts his net wider. He drinks long with ambassadors from Rome—and Rome, from what I hear, is where the action is right now. Every hedge-magician from here to the Tigris is hastening there in search of glory."

Ptolemy shrugged. "So my cousin puts himself in Rome's pocket. Why should they attack me?"

"So that he will be forever in their debt. And meanwhile I'll be dead." I let off a gust of sulphur in annoyance—my master's blithe absorption in his studies could be rather galling. "It's all right for you" I cried. "You can summon up any number of us to protect your skin. What we suffer doesn't matter a fig." I folded my wings over my snout in the manner of a huffy bat and hung from the bedroom rafter.

"Rekhyt—you have saved my life twice over. You know how grateful I am to you."

"Words, words, words. Don't mean nowt."[6]

[6] Bit of Egyptian street argot crept in here. Well, I was riled.

"That's hardly fair. You know the direction of

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher