![Ptolemy's Gate]()

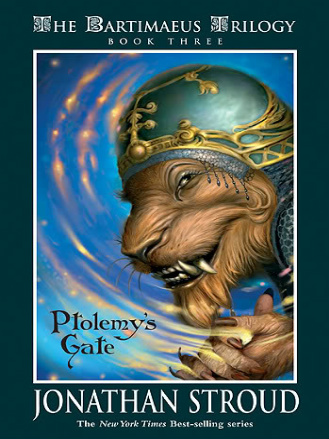

Ptolemy's Gate

London.

The following day Mr. Mandrake breakfasted alone. Ms. Piper, reporting as usual for the early morning briefing, found the door barred by a manservant. The minister was indisposed; he would see her in the office later. Disconcerted, she took her leave.

With leaden steps the magician proceeded to his study. The door guard, attempting a mild jocularity, found itself blasted by a Spasm. Mandrake sat for a long while at his desk, staring at the wall.

Presently he picked up his telephone and dialed a number.

"Hello. Jane Farrar's office? Could I speak with her, please? Yes, it's Mandrake. . . Oh. . . I see. Very well." The receiver was slowly returned to its cradle.

Well, he had tried to warn her. That she had refused to speak to him was hardly his fault. The night before, he had done his best to keep her name out of it, but to no avail. Their altercation had been seen. No doubt she would now be reprimanded too. He felt only mild regret at this; all thought of the beautiful Ms. Farrar filled him with a strange repulsion.

The real stupidity of it was that this trouble might have been prevented if he'd just done what Farrar said. Almost certainly Bartimaeus would have had information on the Jenkins plot that would have helped placate Devereaux. He should have squeezed it out of his slave without a second thought. But instead. . . he had let him go. It was absurd! The djinni was nothing but a thorn in his flesh—abusive, argumentative, feeble. . . and, because of his birth name, potentially a fatal threat. He should have destroyed him while he was unable to fight back. How simple it should have been!

Blank-eyed, he stared at the papers on his desk. Sentimental and weak . . . Perhaps Farrar was right. John Mandrake, minister of the government, had acted against his own interests. Now he was vulnerable to his enemies. Even so, no matter how much cold fury he tried to muster—against Bartimaeus, against Farrar, and most of all against himself—he knew he could not have done otherwise. The sight of the djinni's small, broken body had shocked him too much: it had prompted an impulsive decision.

And this was the shattering event, far more significant than the threats and spite of his colleagues. For years his life had been a fabric of calculations. It was by remorseless dedication to work that Mandrake derived his identity; spontaneity had become alien to him. But now, in the shadow of his single unconsidered action, the prospect of work suddenly did not appeal. Elsewhere this morning, armies were clashing, the ministries were humming: there was much to be done. John Mandrake felt listless, floating, suddenly detached from the demands of his name and office.

A train of thought from the previous night recurred in his mind. An image: sitting with his tutor, Ms. Lutyens, long ago, happily sketching in the garden on a summer's day. . . she sat beside him, laughing, hair gleaming in the light. The vision flickered like a mirage. It vanished. The room was bare and cold.

In due course the magician left his study. In its circle of blackened wood, the door guard flinched from him as he passed.

The day did not go well for Mandrake. At the Information Ministry a tartly worded memo from Ms. Farrar's office awaited him. She had decided to raise an official complaint regarding his refusal to interrogate his demon, an act which was likely to prove detrimental to the police investigation. No sooner had Mandrake finished reading this than a somber deputation from the Home Office arrived, bearing an envelope with a black ribbon. Mr. Collins wished to question him about a serious disturbance in St. James's Park the previous evening. The details were ominous for Mandrake: a fleeing frog, a savage demon set free from its prism, a number of fatalities in the crowd. A minor riot had ensued, with commoners destroying a portion of the fair. Tension on the streets was still high. Mandrake was asked to prepare a defense in time for the Council meeting in two days' time. He agreed without discussion; he knew the thread supporting his career was fraying fast.

During meetings, the eyes of his deputies were amused and scathing. One or two went so far as to suggest he summon his djinni immediately to limit the political damage. Mandrake, stony-faced and stubborn, refused. All day he was irritable and distracted; even Ms. Piper gave him a wide berth.

By late afternoon, when Mr. Makepeace rang to remind him of their appointment, Mandrake had

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher