![Sidney Chambers and The Shadow of Death (The Grantchester Mysteries)]()

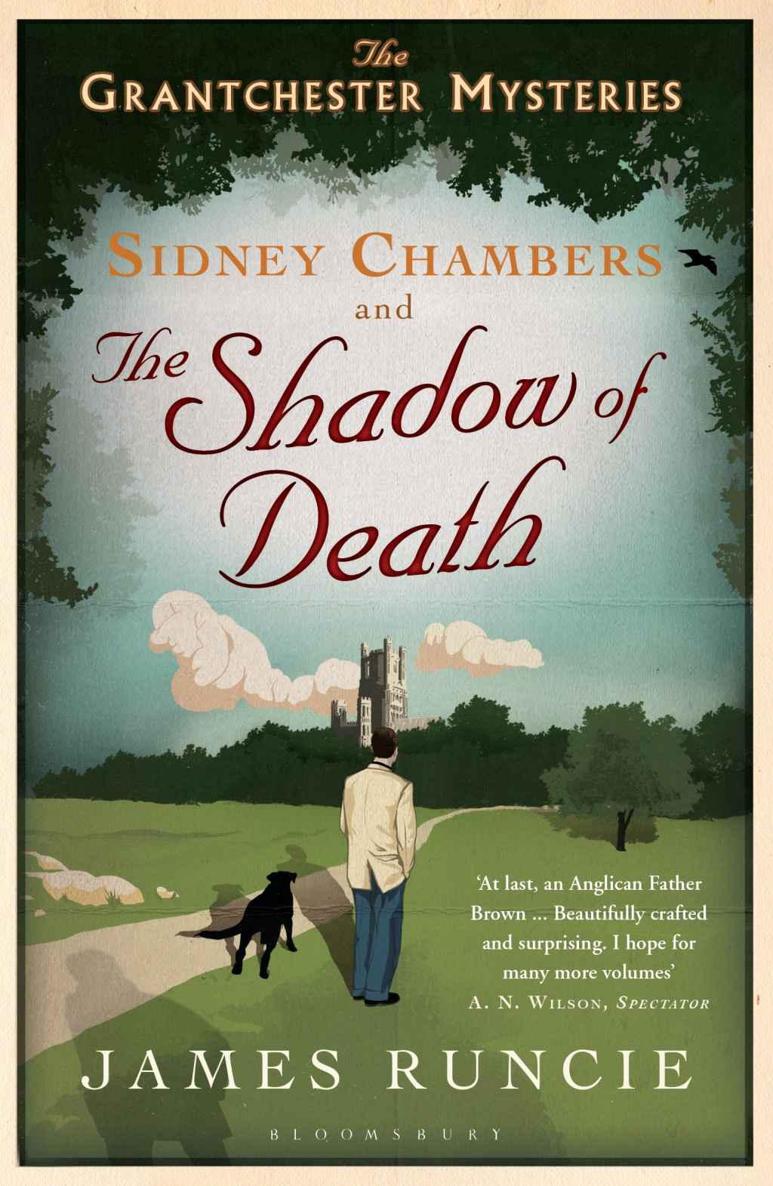

Sidney Chambers and The Shadow of Death (The Grantchester Mysteries)

was on the verge of being discovered, he blew his brains out. It’s common enough, man. Re-double?’

‘Of course.’ Sidney threw again. ‘Ah . . . I think I can re-enter the game.’ He placed his checker on the twenty-three point. ‘Did he leave a note?’

Inspector Keating was irritated by this question. ‘No, Sidney, he did not leave a note.’

‘So there’s margin for error?’

The inspector leaned forward and shook again. He had thought he had the game in the bag but now he could see that Sidney would soon start to bear off. ‘There is no room for doubt in this case. Not every suicide leaves a note . . .’

‘Most do.’

‘My brother-in-law works in the force near Beachy Head. They don’t leave a lot of notes down there, I’m telling you. They take a running jump.’

‘I imagine they do.’

‘Our man killed himself, Sidney. If you don’t believe me then go and pay the widow one of your pastoral visits. I’m sure she’d appreciate it. Just don’t start having any ideas.’

‘I wouldn’t dream of it,’ his companion lied, anticipating an unlikely victory on the board.

The living at Grantchester was tied to Sidney’s old college of Corpus Christi, where he had studied theology and now took tutorials and enjoyed dining rights. He enjoyed the fact that his work combined the academic and the clerical, but there were times when he worried that his college activities meant that he did not have enough time to concentrate on his pastoral duties. He could run his parish, teach students, visit the sick, take confirmation classes and prepare couples for marriage, but he frequently felt guilty that he was not doing enough for people. In truth, Sidney sometimes wished that he were a better priest.

He knew that his responsibility to the bereaved, for example, extended far beyond the simple act of taking a funeral. In fact, those who had lost someone they loved often needed more comfort after the initial shock of death had gone, when their friends had resumed their daily lives and the public period of mourning had passed. It was the task of a priest to offer constant consolation, to love and serve his parishioners at whatever cost to himself. Consequently, Sidney had no hesitation in stopping off on his way into Cambridge the next morning to call on Stephen Staunton’s widow.

The house was a mid-terrace, late-Victorian building on Eltisley Avenue, a road that lay on the edge of the Meadows. It was the kind of home young families moved to when they were expecting their second child. Everything about the area was decent enough but Sidney could not help but think that it lacked charm. These were functional buildings that had escaped wartime bombing but still had no perceivable sense of either history or local identity. In short, as Sidney walked down the street, he felt that he could be anywhere in England.

Hildegard Staunton was paler than he remembered from her husband’s funeral. Her short hair was blonde and curly; her eyes were large and green. Her eyebrows were pencil-thin and she wore no lipstick; as a result, her face looked as if her feelings had been washed away. She was wearing a dark olive housecoat, with a shawl collar and cuffed sleeves that Sidney only noticed when she touched her hair; worrying, perhaps, that she needed a shampoo and set but could not face a trip to the hairdresser.

Hildegard had been poised yet watchful at the service, but now she could not keep still, standing up as soon as she had sat down, unable to concentrate. Anyone outside, watching her through the window, would probably think she had lost something, which, of course, she had. Sidney wondered if her doctor had prescribed any medicine to help her with her grief.

‘I came to see how you were getting on,’ he began.

‘I am pretending he is still here,’ Hildegard answered. ‘It is the only way I can survive.’

‘I am sure it must feel very strange.’ Sidney was already uncomfortable with the knowledge of her husband’s adultery, let alone potential murder.

‘Being in this country has always seemed strange to me. Sometimes I think I am living someone else’s life.’

‘How did you meet your husband?’ Sidney asked.

‘It was in Berlin after the war.’

‘He was a soldier?’

‘With the Ulster Rifles. The British Foreign Office sent people over to “aerate” us, whatever that meant, and we all went to lectures on Abendländische Kultur . But none of us listened very much. We

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher