![Sidney Chambers and The Shadow of Death (The Grantchester Mysteries)]()

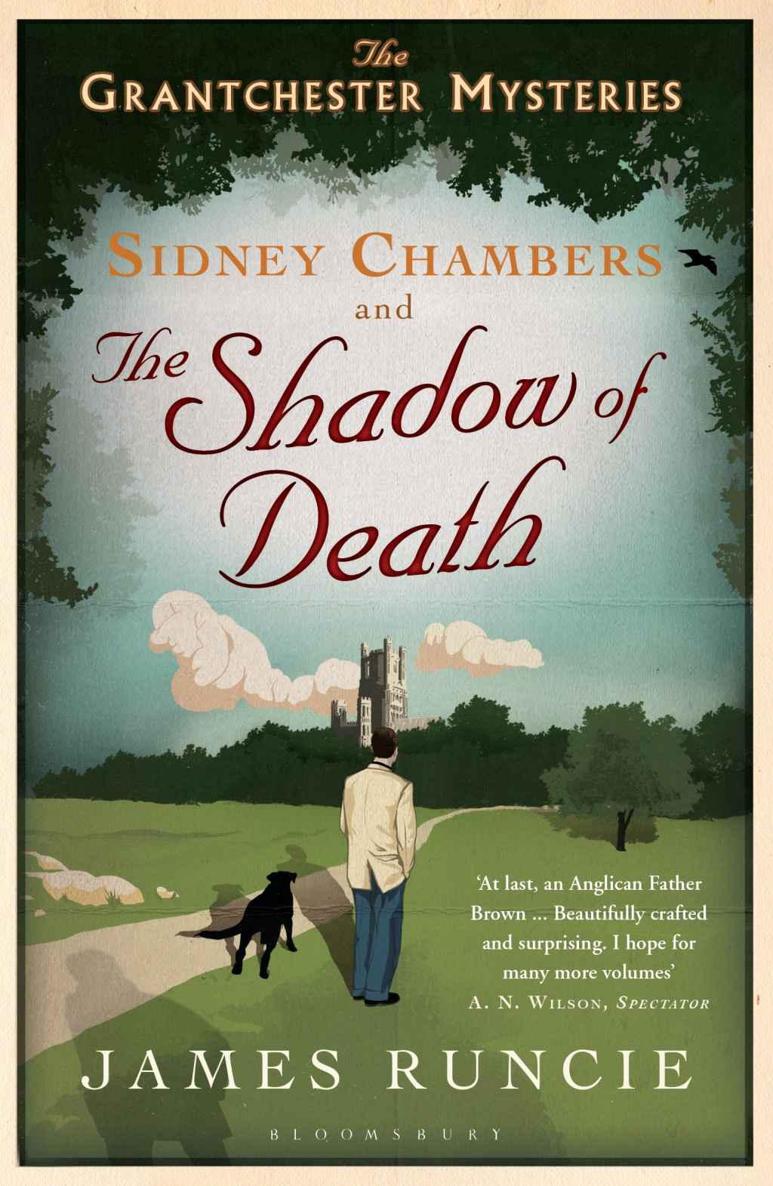

Sidney Chambers and The Shadow of Death (The Grantchester Mysteries)

responses:

‘O God make speed to save us.’

The choirboys replied:

‘O Lord make haste to help us.’

‘Singing is the sound of the soul,’ he thought to himself. For centuries people had been singing these words. Such continuity gave Sidney hope. He was part of something greater than himself – not only history but beauty, continuity and, he hoped, truth.

He prayed for the soul of Stephen Staunton. We will live as we have never lived . Those had been his last words to Pamela Morton and yet, perhaps, they also spoke of a world beyond our own.

He looked up at the darkened stained glass. He had learned more about love in the past few weeks than he had known in years. He had seen some of its characteristics: how it could be passionate, jealous, tolerant, forgiving and long-lasting. He had seen it disappear, and he had seen it turn into hatred. It was the most unpredictable and chameleon of emotions, sometimes sudden and unstable, able to flare up and die down; at other times loyal and constant, the pilot flame of a life.

Sidney touched his hands together in prayer. Then he gave himself up into silence. ‘How we love determines how we live,’ he thought.

A Question of Trust

It was the afternoon of Thursday 31 December 1953, and a light snow that refused to settle drifted across the towns and fields of Hertfordshire. Sidney was tired, but contented, after the exertions of Christmas and was on the train to London. He had seen the festival season through with a careful balance of geniality and theology and he was looking forward to a few days off with his family and friends.

As the train sped towards the capital, Sidney looked out of the window on to the backs of small, suburban houses and new garden cities; a post-war landscape full of industry, promise and concrete. It was a world away from the village in which he lived. He was almost the countryman now, a provincial outsider who had become a stranger in the city of his birth.

He started to think about the question of belonging and identity: how much a person was defined by geography, and how much by upbringing, education, profession, faith and choice of friends.

‘How much can a person change in a life?’ he wondered.

It was an idea at the heart of Christianity, and yet many people retained their essential nature throughout their lives. He certainly didn’t expect too radical a departure in the behaviour of the friends he was due to meet that evening.

As the train pulled in to Kings Cross, Sidney was determined to remain cheerful in the year ahead. He believed that the secret of happiness was to concentrate on things outside oneself. Introspection and self-awareness were the enemies of contentment, and if he could preach a sermon about the benefits of selflessness, and believe in it without sounding too pious, then he would endeavour to do so that very Sunday.

He put on his trilby, gathered his third umbrella of the year – he had left the previous two on earlier journeys – and alighted in search of a bus that would take him to the party in St John’s Wood.

His New Year’s Eve dinner was to be hosted by his old friend Nigel Thompson. Educated at Eton and Magdalene College, Cambridge, Nigel had been tipped as a future Prime Minister while still at university and had become Chairman of the Young Conservatives straight after the war. Having been elected as the Member of Parliament for St Marylebone in the 1951 General Election, he began his rise to power as PPS to Sir Anthony Eden (a man his father had known from the King’s Rifle Corps), and now worked as Joint Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs. Sidney was therefore looking forward to a few meaty conversations about Britain’s role on the international stage with one of the most promising MPs in the country.

His wife, Juliette, had been the Zuleika Dobson of their generation, possessing a porcelain complexion, Titianesque hair and a willowy beauty that her dream-like manner could only enhance. Sidney had worried at their wedding whether she had the stamina necessary to be the wife of an MP but cast such masculine thoughts aside as the first intimations of jealousy.

Their home was a nineteenth-century terraced house to the north of Regent’s Park. It had previously been the type of establishment in which rich Victorian men had kept their decorative mistresses. Sidney considered this rather appropriate as Juliette Thompson certainly had a whiff of the

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher