![Sidney Chambers and The Shadow of Death (The Grantchester Mysteries)]()

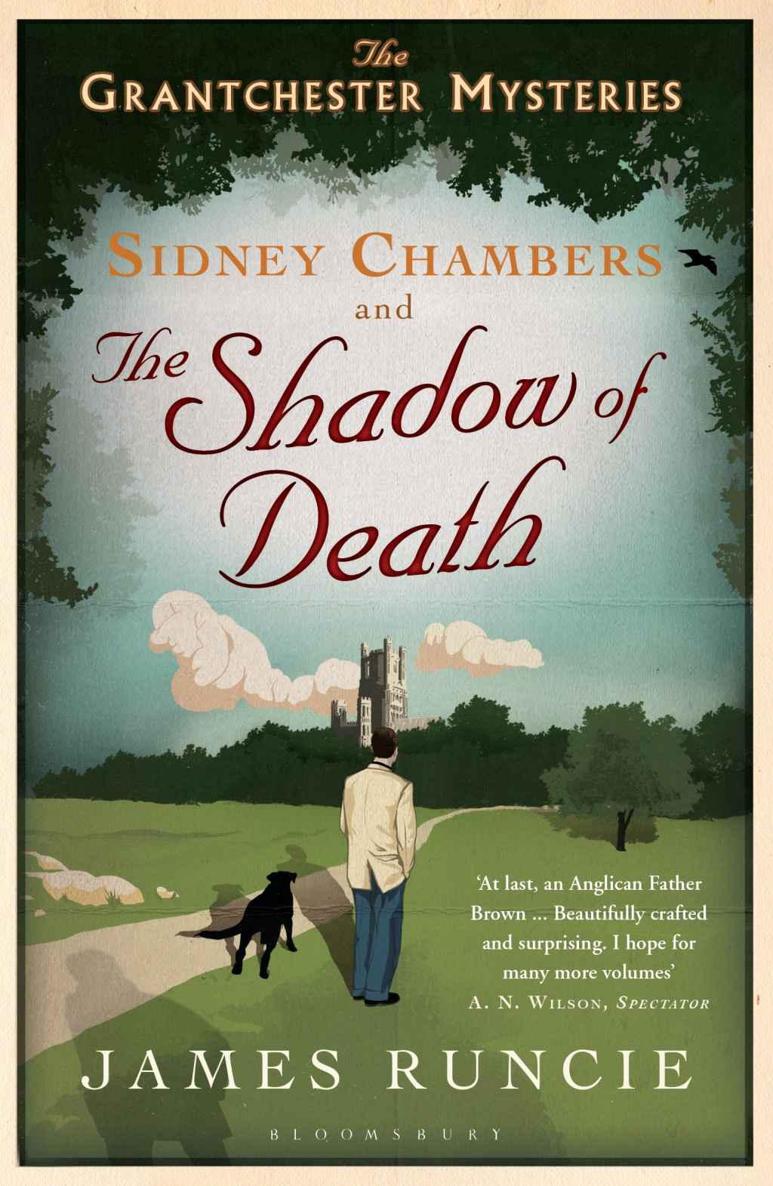

Sidney Chambers and The Shadow of Death (The Grantchester Mysteries)

Pre-Raphaelite about her. Her beauty was both doomed and untouchable: unless, of course, you were Nigel Thompson MP.

Sidney got off the bus at the stop for Lord’s Cricket Ground and made his way towards Cavendish Avenue. He was not an admirer of London in winter, with its wet streets, fetid air and gathering smog, but he recognised that this was where his family and friends earned their living and that if he wanted to enjoy the congeniality of their homes and the warmth of their fireplaces then he had to put up with any inconvenience in getting to them.

At least, Sidney remembered, his sister Jennifer would be at the dinner. His younger sibling had a naturally good-natured manner, with a rounder face than the rest of the family, eager brown eyes and a bob cut that framed her face and gave the impression, Sidney thought, of a circle of friendliness. She was always glad to see her brother; and he felt his heart lift every time she came into the room.

Traditionally, Jennifer was considered the most responsible member of the family but on this particular evening she was to bring a rather shady new boyfriend to the dinner: Johnny Johnson.

She had briefed her brother about him during the family telephone call on Christmas Day, and she had high hopes that Sidney would approve of him: not least because he and his father ran a jazz club. He was ‘a breath of fresh air’, and he did, apparently, ‘a million and one amazing things’. Sidney only hoped that his sister was not going to become besotted too soon. The family trait of thinking the best of people had resulted in the past in her having rather too fanciful expectations about the ability of men to make lasting commitments, and this had, inevitably, led to disappointment.

They were to be joined by Jennifer’s best friend and flatmate, Amanda Kendall, who had just begun her career as a junior curator at London’s National Gallery.

When Sidney had first met Amanda, soon after her twenty-first birthday, he had been rather smitten. She was the tall and vivacious daughter of a wealthy diplomat who had once been a colleague of his grandfather. Unlike Juliette Thompson, she was not what a fashion magazine would refer to as an ‘English rose’, being dark and commanding and full of opinion. But she had presence, and even though her own mother had described her nose as ‘disappointingly Roman’, dinner parties throughout London were grateful for her conversational sparkle. It was universally considered that, although she might cause trouble with her outspoken views, Amanda could liven up any party and would be a good catch for any man who was prepared to take her on. Sidney had nurtured a faint hope that one day he might be that man, but as soon as he had decided to become a clergyman, that aspiration had bitten the dust. It would have been ludicrous for a well-connected debutante, in pursuit of the most eligible bachelor in town, to marry a vicar.

Now, after several years of careful research, Amanda appeared to have got her man. On one of her recent trips to assess the potential death duty on a series of paintings in a Wiltshire stately home, she had met the allegedly charming, undoubtedly wealthy, extraordinarily good-looking and unfortunately ill-educated Guy Hopkins. This was the man to whom she was to be engaged, perhaps even, it had been suggested, that very night.

Sidney’s official companion at dinner was the renowned socialite Daphne Young, a terrifyingly thin woman who was famed both for her sharp intelligence and for the number of marriage proposals she had turned down. Consequently, he rather dreaded the disappointment that even someone so well mannered would be unable to conceal on discovering that her dining companion that evening was going to be a clergyman.

At least the other two guests at the dinner were relatively jovial: Mark Dowland, a publisher who was delightfully indiscreet about his authors, and his small and spiky wife Mary, a zoologist with piercing blue eyes and the sharpest of tongues. The softest thing about her, her husband had once remarked, was her teeth.

Sidney had never been that keen on New Year’s Eve. It was, perhaps, the thought of yet another year passing, a reminder of all the time that he had frittered away in the previous twelve months and the secular conviviality so soon after Christmas. He sometimes wondered what it might be like to take to his bed until it was over, and remembered a fellow priest who, when he

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher