![Sidney Chambers and The Shadow of Death (The Grantchester Mysteries)]()

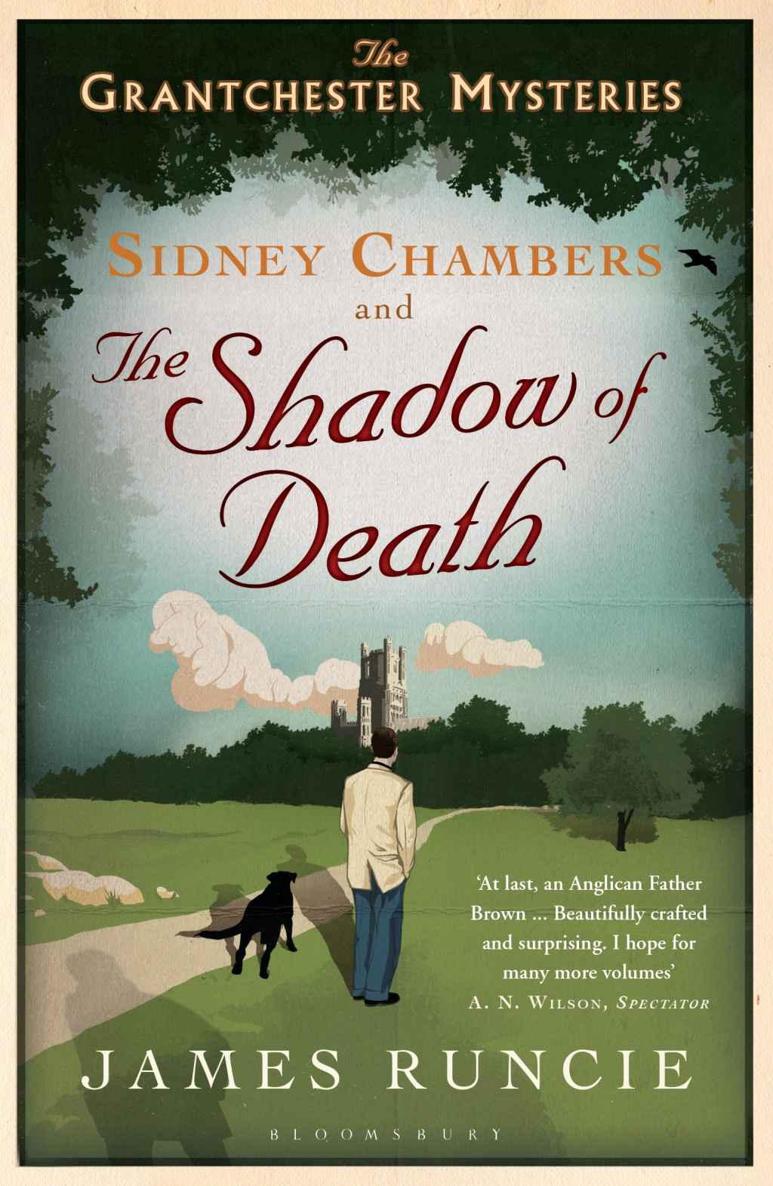

Sidney Chambers and The Shadow of Death (The Grantchester Mysteries)

dog. His presence brought new challenges – discipline, training, routine – but also, it had to be said, benefits. Although his desire for attention and reward could be relentless, Sidney found that his Labrador was not only an ice-breaker with new parishioners but also, crucially, a conversation-stopper. In fact Dickens freed Sidney from the time-consuming complaints of the more troublesome members of his congregation. If the dog strained at the leash or made a mad dash after rabbits then his owner would have to break off his conversation and follow Dickens’s mazy runs across the Meadows. The dog’s sudden bursts of speed or changes of direction were, Sidney decided, like an improvised saxophone solo. You never knew what was going to happen next.

It was, perhaps, not surprising that Sidney should think in these terms for he considered himself to be something of a jazz aficionado. While he loved the concentrated serenity of choral music, and the work of Byrd, Tallis and Purcell in particular, there were times when he wanted something earthier. And so, on his rare evenings at home, he liked nothing better than to listen to the latest hot sounds from America coming from the wireless. It was the opposite of stillness, prayer and penitence, he thought; full of life, mood and swing, whether it was ‘It Don’t Mean a Thing’ by the Ralph Sharon Sextet or the ‘Boogie Woogie Stomp’ of Albert Ammons. Jazz was unpredictable. It could take risks, change mood, announce a theme, develop, change and recapitulate. It was all times in one time, Sidney thought, reworking themes from the past, existing in the present, while creating expectations about any future direction it might take. It was a metaphor of life itself, both transient and profound, pursuing its course with intensity and freedom. Everyone, Sidney was sure, felt the vibe differently, although he was careful not to use a word such as ‘vibe’ when he dined at his College high table.

Jazz was Sidney’s treat to himself, and today he was going to share his enjoyment by travelling to London with Inspector Keating to hear the Gloria Dee Quartet in Soho. They were to be Johnny Johnson’s guests as a thank you gesture after the business of the missing ring. Sidney had not felt it necessary to admit that the friend he was bringing was a policeman; nor had he told Keating that Johnny’s father was none other than the reformed burglar Phil ‘the Cat’ Johnson. He did not want to over-excite his friend.

Gloria Dee had come over from New York City and was already being tipped as the new Bessie Smith. She had the same dramatic presence, together with a voice that could range from supreme tenderness to gospel power. All the reviewers on the jazz scene had praised both the clarity of her diction and her incomparable phrasing and timing.

Sidney was glad to be so up to the minute in his appreciation of her talents but was nervous whether Geordie would like it. He had him down as a light opera man. He also worried that the inspector would be wary of Soho’s seediness.

However, as soon as they arrived in London, Keating seemed unusually cheerful. ‘Makes a change from our usual arrangement,’ he told Sidney as they left Leicester Square and crossed into Chinatown. ‘And it’s good to get out of Cambridge. It can feel a bit claustrophobic, don’t you think?’

‘I worry that you may find the club just as confined.’

‘Sometimes you worry too much.’

‘And remember, Geordie, we are off duty . I am not a clergyman and you are not a detective.’

‘We are never off duty, Sidney, you know that.’

‘Do you mean to say there’s no peace for the wicked?’

They climbed the stairs up to the club and handed their coats to Colin on the door. As they walked in, Sidney began to feel self-conscious. The club was crowded with men in sharp suits and thin ties who sat close to women in tight blouses, full skirts and dancing shoes. They were smoking and drinking, and mellow with the mood. Although Sidney was dressed in civvies – a grey flannel double-breasted suit with two-tone brogues – he still felt like a clergyman. He wondered whether he should have opted for a Homburg hat, or forsaken the tie which, he realised, was an episcopal purple, but it was too late to worry about that now.

Johnny Johnson greeted the two men and, after introductions had been made and the beers had been ordered, they sat down to await the evening’s entertainment. A young

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher