![The Chemickal Marriage]()

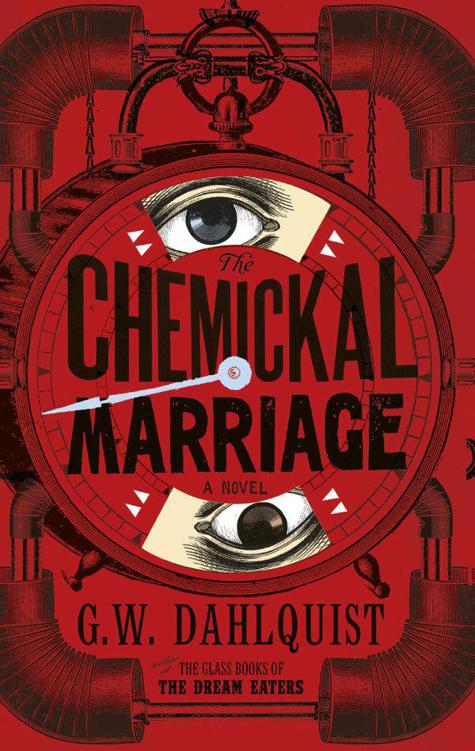

The Chemickal Marriage

rest. And information.’

‘But we

have

learnt much,’ said Svenson. ‘The new explosive, the glass spurs – that they are inscribed with an emotion instead of a memory.’

‘We’ve no idea what that

means

.’

‘Not yet, but have you ever eaten hashish?’

‘I beg your pardon,’ said Phelps.

‘I am thinking of the glass – the

anger

, a state of pure emotion –’

‘You think the glass contains

hashish

?’

‘Not at all. Consider Hassan i-Sabbah and his guild of assassins, who entered a state of deadly single-mindedness under the combined influences of religion and narcotics. Think of the Thuggee cult of India – incense, incantations,

soma

– the principle is the same.’

‘Not unlike the Process,’ observed Chang.

Phelps managed to exhale without coughing. ‘The glass may answer for the narcotic, yet if the spurs hold no memory, where is the instruction? Without

thought

, how can Vandaariff direct those stricken?’

‘Perhaps he cannot.’ Svenson sighed ruefully. ‘Do not forget, the man

believes

his alchemical religion. We mistake him if we seek only reason.’

Chang knew Svenson was right – he had seen the unsettling glow behind Vandaariff’s eyes – yet he said nothing about the ‘elemental’ glass cards, or the too-rapid restoration of his own strength. He ought to have described the whole thing then and there – if there was any man to make sense of things, it was the Doctor – but such disclosure would have led to a public scrutiny of his wound. Chang waited until Svenson put more coal in the stove before carefully stretching the muscles of his lower back. He felt no pain or inhibition of movement. Was it possible that Vandaariff had merely healed him, and that the others had stared only at the vicious nature of the scar?

A faint but high-pitched gasp came from behind Miss Temple’s curtain. The three men looked at each other.

‘Celeste?’ asked Svenson.

‘Do go on,’ she replied quickly. ‘It was but a splinter on my chair.’

Svenson waited, but she said nothing more. ‘Are you all right?’

‘Goodness, yes. Do not mind me in the least.’

The trousers were not completely dry, but Chang reasoned that wearing them slightly damp would settle the leather more comfortably around his body. To hide his wound from Svenson he made a point of shucking off hisblanket with his back to the wall. Tucking in the silk shirt, stained by its time in the canal, he caught a flicker of movement at the edge of the curtain. Had she been peeking? Disliking the entire drift of his thoughts, Chang strode past the others and slipped into the cold afternoon sun.

The hut was surrounded by squat pine trees. Chang did not relish another bare-footed tramp through twigs and stones, but saw no alternative, and so set off, keeping to the mud and dry leaves. As he reached the other huts, he saw one whose door hung open several inches. Smoke rose from the chimney – indeed it now came from several huts, none of which had seemed occupied before – and from inside he could hear footsteps.

Chang snapped his head back from the door at the wheeling movement of a pistol being drawn and the click of its hammer.

‘Do not shoot me, Mr Cunsher.’

If Cunsher was in the service of their enemies, this was the perfect opportunity to blow Chang’s head off and explain it away as an accident. But the man had already lowered the gun. Chang stepped inside and nodded to the stove.

‘Our company does not suit you?’

Cunsher shrugged. His accented speech slipped from his mouth as if each ill-fitting word had been oiled. ‘One smoking stove reveals our refuge. Four stoves make a party of stonecutters.

Here

– for you.’

Cunsher tossed a pair of worn black boots in Chang’s direction. Chang saw the leather was still good and the soles were sound. He wormed his foot inside one, stepped down on the heel, and then rolled his ankle in a circle.

‘It’s a damned miracle. Where did you find them? How did you know the size?’

‘Your feet of course – and then I have

looked

. Here.’ Cunsher took a pair of thin black goggles from a wooden crate. ‘Used for blasting. The Doctor related your requirements.’

Chang slipped the goggles on. The lenses were every bit as dark as his habitual glasses, but came edged with leather to block peripheral glare. Already he felt his muscles relaxing.

‘Thank you again. I had despaired.’

Cunsher tipped his head. ‘And you are dry. The others? We

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher