![The Chemickal Marriage]()

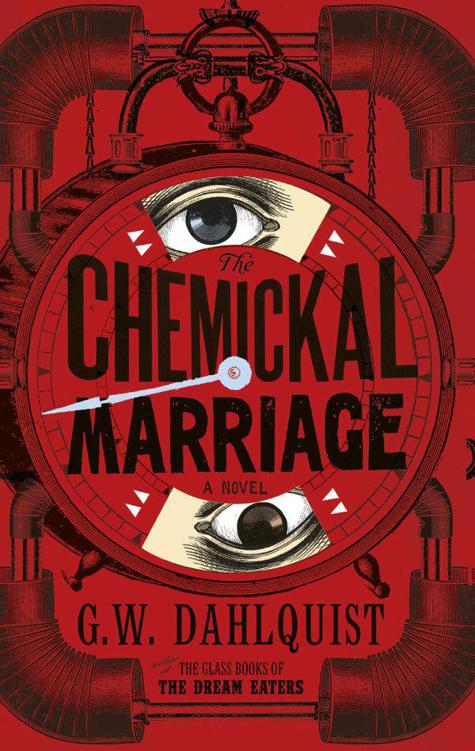

The Chemickal Marriage

cathedral. Such destruction cannot, of course, deter my errand. I require a man called Pfaff. Yellow hair, with an ugly orange coat. He will have been taken by your constables at the Seventh Bridge, or near the Palace.’

The warder paused. Chang cocked his head, as if listening for the man’s compliance.

‘Ah, well, sir –’

‘I expect you require a writ.’

‘I do, sir, yes. Standard custom –’

‘I have lost all such documents, along with my assistant, Father Skoll. Father Skoll’s

arms

, you see. Left like the poor doll of a wicked child.’

‘How horrid, sir –’

‘Thus I lack your

writ

.’ Chang could sense a restless line forming behind him, and made a point to speak more lingeringly. ‘The document case was in his

hands

, you understand. Shattered altogether. One would have thought poor Skoll a porcupine for the splinters –’

‘Jesus Lord –’

‘But perhaps you can make it right. Pfaff is a negligible villain, yet important to His Lordship. Do you have him here or not?’

The warder looked helplessly at the growing queue. He pushed the log book to Chang. ‘If you would just

sign

…’

‘How can I sign if I can’t see?’ mused Chang. Without waiting for an answer he groped broadly for the warder’s pen and obligingly scrawled – ‘Lucifera’ filling half the page.

Chang made his deliberate, tapping way inside, to another warder with another book. The warder ran an ink-stained finger down the page. ‘When delivered?’

‘Last night,’ Chang replied. ‘Or early this morning.’

The warder’s face settled in a frown. ‘We’ve no such name.’

‘Perhaps he gave another.’

‘Then he could be anyone. I’ve five hundred souls in the last twelve hours alone.’

‘Where are the men arrested at the Seventh Bridge – or the Palace, or St Isobel’s? You

know

the ones I mean. Delivered by the Army.’

The warder consulted his papers. ‘Still don’t have any man named Pfaff.’

‘With a

p

.’

‘What?’

‘Surely you have those men all rounded into one or two large cells.’

‘But how will you know if he’s there? You can’t see.’

Chang rapped the tip of his stick on the tiles. ‘God can always smell a villain.’

Chang had three times been in the Marcelline, on each occasion luckily redeemed before proceedings advanced to outright torture, and it was with a shiver that he descended to the narrow tiers. Chang did not expect the guards to recognize him – the cleric’s authority granted him an automatic deference – but a sharp-eyed prisoner might call out anything. If Chang

was

recognized, he had placed himself well beyond hope.

The corridors were slick with filth. Shouts rang out as he passed each cell – pleas for intervention, protests of innocence, cries of illness. He did not respond. The passage ended at a particularly large, iron-bound door. Chang’s guide rattled his truncheon across the viewing-hole and shouted that ‘any criminal named Pfaff’ had ten seconds to make himself known. A chorus of yells came in reply. Without listening, the guard roared that the first man claiming to be Pfaff but found to be an impostor would get forty lashes. The cell went quiet.

‘Ask for

Jack

Pfaff,’ suggested Chang. He looked at the other cells along the corridor, knowing the guard’s voice would carry, and that if Pfaff were elsewhere in the Marcelline he might hear. The guard obligingly bawled it out. There was no response. Despite the increased chance of recognition, Chang had no choice.

‘Open the door. Let me in.’

‘I can’t do that, Father –’

‘Obviously the man is hiding. Will you let him make us fools?’

‘But –’

‘No one will harm me. Tell them that if they try, you will slaughter every man. All will be well – it is a matter of knowing the sinning mind.’

The cell held at least a hundred men, crowded close as in a slave ship. The guard waded in, swinging his truncheon to make room. Chang entered a ring of faces that gleamed with sweat and blood.

Pfaff was not there. These were the refugees Chang had seen in the alleys and along the river – their only sins poverty and bad luck. Most were victims of Vandaariff’s weapon, beaten into submission after the glass spurs had set them to a frenzy. Chang doubted half would live the night. He extended his stick to the rear, waving generally – since he could not see – but guiding the guard’s attention to where a vaulting arch of brick created a tiny

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher