![The Complete Aristotle (eng.)]()

The Complete Aristotle (eng.)

same and share in no change.

Further, if there is movement, there is also something moved,

and everything is moved out of something and into something; it

follows that that that which is moved must first be in that out of

which it is to be moved, and then not be in it, and move into the

other and come to be in it, and that the contradictory statements

are not true at the same time, as these thinkers assert they

are.

And if the things of this earth continuously flow and move in

respect of quantity-if one were to suppose this, although it is not

true-why should they not endure in respect of quality? For the

assertion of contradictory statements about the same thing seems to

have arisen largely from the belief that the quantity of bodies

does not endure, which, our opponents hold, justifies them in

saying that the same thing both is and is not four cubits long. But

essence depends on quality, and this is of determinate nature,

though quantity is of indeterminate.

Further, when the doctor orders people to take some particular

food, why do they take it? In what respect is ‘this is bread’ truer

than ‘this is not bread’? And so it would make no difference

whether one ate or not. But as a matter of fact they take the food

which is ordered, assuming that they know the truth about it and

that it is bread. Yet they should not, if there were no fixed

constant nature in sensible things, but all natures moved and

flowed for ever.

Again, if we are always changing and never remain the same, what

wonder is it if to us, as to the sick, things never appear the

same? (For to them also, because they are not in the same condition

as when they were well, sensible qualities do not appear alike;

yet, for all that, the sensible things themselves need not share in

any change, though they produce different, and not identical,

sensations in the sick. And the same must surely happen to the

healthy if the afore-said change takes place.) But if we do not

change but remain the same, there will be something that

endures.

As for those to whom the difficulties mentioned are suggested by

reasoning, it is not easy to solve the difficulties to their

satisfaction, unless they will posit something and no longer demand

a reason for it; for it is only thus that all reasoning and all

proof is accomplished; if they posit nothing, they destroy

discussion and all reasoning. Therefore with such men there is no

reasoning. But as for those who are perplexed by the traditional

difficulties, it is easy to meet them and to dissipate the causes

of their perplexity. This is evident from what has been said.

It is manifest, therefore, from these arguments that

contradictory statements cannot be truly made about the same

subject at one time, nor can contrary statements, because every

contrariety depends on privation. This is evident if we reduce the

definitions of contraries to their principle.

Similarly, no intermediate between contraries can be predicated

of one and the same subject, of which one of the contraries is

predicated. If the subject is white we shall be wrong in saying it

is neither black nor white, for then it follows that it is and is

not white; for the second of the two terms we have put together is

true of it, and this is the contradictory of white.

We could not be right, then, in accepting the views either of

Heraclitus or of Anaxagoras. If we were, it would follow that

contraries would be predicated of the same subject; for when

Anaxagoras says that in everything there is a part of everything,

he says nothing is sweet any more than it is bitter, and so with

any other pair of contraries, since in everything everything is

present not potentially only, but actually and separately. And

similarly all statements cannot be false nor all true, both because

of many other difficulties which might be adduced as arising from

this position, and because if all are false it will not be true to

say even this, and if all are true it will not be false to say all

are false.

<

div id="section125" class="section" title="7">

7

Every science seeks certain principles and causes for each of

its objects-e.g. medicine and gymnastics and each of the other

sciences, whether productive or mathematical. For each of these

marks off a certain class of things for itself and busies itself

about this as about something existing and real,-not however qua

real; the science that does this is another distinct from these. Of

the sciences mentioned each gets somehow the

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher

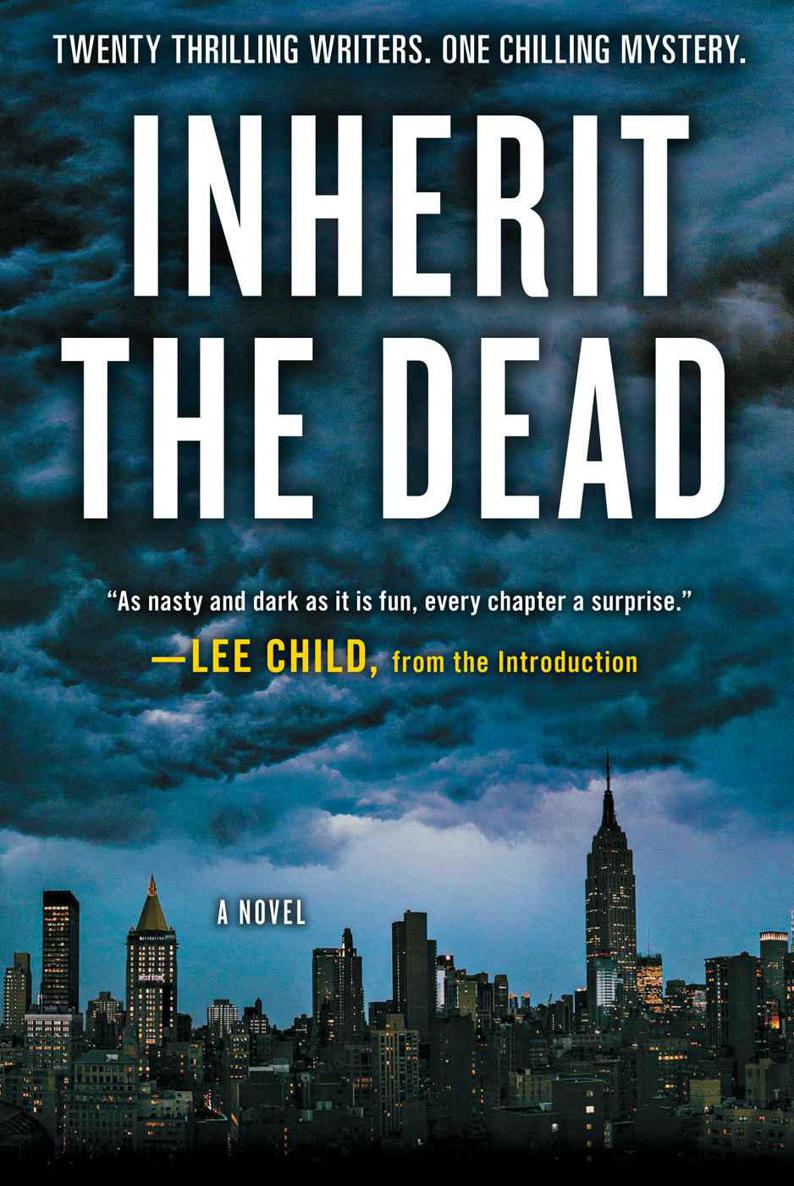

![Inherit the Dead]()

Inherit the Dead Online Lesen

von

Jonathan Santlofer

,

Stephen L. Carter

,

Marcia Clark

,

Heather Graham

,

Charlaine Harris

,

Sarah Weinman

,

Alafair Burke

,

John Connolly

,

James Grady

,

Bryan Gruley

,

Val McDermid

,

S. J. Rozan

,

Dana Stabenow

,

Lisa Unger

,

Lee Child

,

Ken Bruen

,

C. J. Box

,

Max Allan Collins

,

Mark Billingham

,

Lawrence Block