![The Lesson of Her Death]()

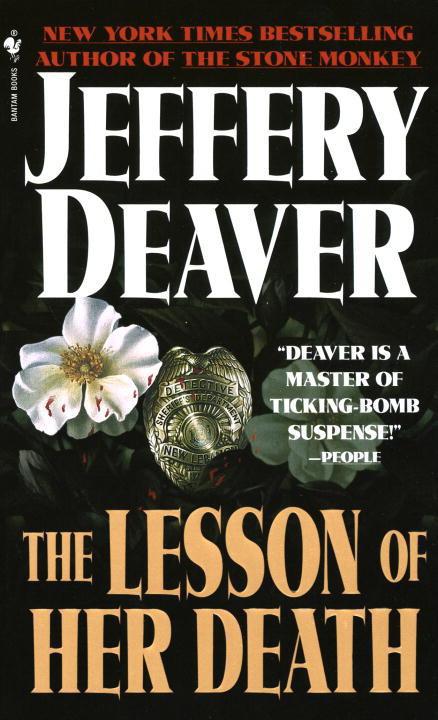

The Lesson of Her Death

heart.

He raged. Jennie

was

what he wanted. His tongue made a foray into the crevice of his lips and he tasted her. That was proof, that was the metaphor:

he hungered for her

. He cried in front of her while she lookedon maturely, head cocked with affection. He blurted a shameful stream: he was willing to do whatever she wanted, get a job in the private sector, work for a commercial magazine, edit.… He had purged himself with all the hokey melodrama of mid-list literature.

Brian Okun, radiant scholar of the esoteric grafting of psychology and literature, recognized this obsessive effluence for what it was. So he was not surprised when, in an instant, love became hate. She had seen him vulnerable, she had comforted him—this, the only woman who had ever rejected him—and he detested her.

Even now, months after this incident, a day after her murder, Okun felt an uncontrollable surge of anger at her, for her simpering patronizing

Mutterheit

. He was back on the Nobel path, yes. But she had shaken something very basic in his nature. He had lost control, and his passions had skidded violently like a car on glazed snow. He hated her for that.

Ah, Jennie, what have you done to me?

Brian Okun pushed his hands together and waited for the trembling to stop. It did not. He breathed deeply and hoped for his heart to calm. It did not. He thought that if only Jennie Gebben had accepted his proposal, his life would be so unequivocally different.

The smell of the halls suggested something temporary: Pasty, cheap paint. Sawdust. Air fresheners and incense covering stale linens. Like a barracks for refugees in transit. The color of the walls was green and the linoleum flecked stone gray.

Bill Corde knocked on the door. There was no answer.

“Ms. Rossiter? I’m from the Sheriff’s Department.”

Another knock.

Maybe she’d gone to St. Louis for the funeral.

He glanced behind him. The corridor was empty. He tried the knob and pushed the door open.

A smell wafted out and surrounded him. Jennie Gebben’s spicy perfume. Corde recognized it immediately. He lifted his hand and smelled the same scent—residue from the bottle on her dressing table at home.

Corde hesitated. This was not a crime scene and students in dormitories retained rights of privacy and due process. He needed a warrant in hand to even step into the room.

“Ms. Rossiter?” Corde called. When there was no answer he walked inside.

The room Jennie and Emily shared had a feeble symmetry. Bookcases and mirrors bolted to opposite walls. The beds parallel to each other but the desks turned at different angles—looking up from a textbook, one girl would look out the small window at the parking lot; the other would gaze at a bulletin board. On one bed rested a stuffed rabbit.

Corde examined Jennie’s side of the room. A cursory look revealed nothing helpful. Books, notebooks, school supplies, posters, souvenirs, photos of family members (Corde noticing that the young Jennie bore a striking resemblance to Sarah), makeup, hair curlers, clothes, scraps of paper, packages of junk desserts, shampoos, lotions. Shear pastel underwear hung on a white string to dry. A U2 poster, stacks of cassettes, a stereo set with a cracked plastic front. A large box of condoms (latex, he noted, not the lambskin found at the crime scene). Thousands of dollars’ worth of clothes. Jennie was a meticulous housekeeper. She kept her shoes in little green body bags.

Corde noticed a picture of two girls: Jennie and a brown-haired girl of delicate beauty. Emily? Was it the same girl in one of the pictures on Jennie’s wall at home? Corde could not remember. They had their arms around each other and were mugging for the camera. Their black and brown hair entwined between them and made a single shade.

A clattering of laughter from the floor above remindedhim that he was here without permission. He set the picture down and turned toward Jennie’s desk.

He crested the rise on 302 just in front of his house.

Corde had ticketed drivers a dozen times for sprinting along this strip at close to sixty. It was a straightaway, posted at twenty-five after a long stretch of fifty, so you couldn’t blame them for speeding, Corde supposed. But it was a straightaway in front of

his

house where

his

kids played. When he wasn’t in the mood to ticket he took to leaving the squad car parked nose out in the drive, which slowed the hot-rodders down considerably and put a slew of brake marks on the

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher