![The Lesson of Her Death]()

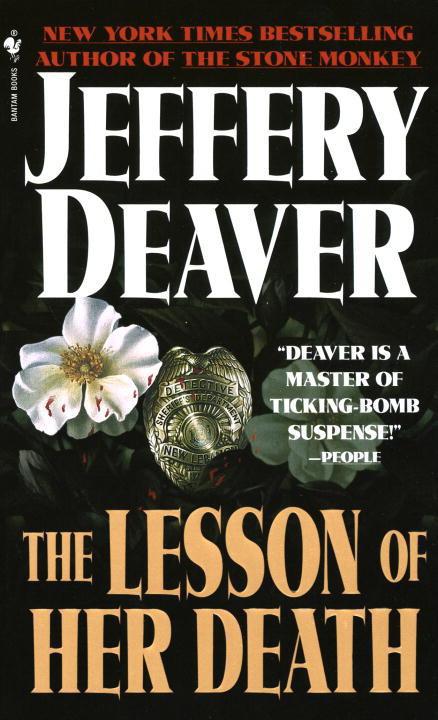

The Lesson of Her Death

repeated the question. Sarah nodded.

“Why?” her father demanded.

“Because.”

“Sarah—” Corde began sternly.

The little girl seemed to wince. “It’s not my fault. The wizard

told

me to.”

“The wizard?”

“The Sunshine Man …”

This was one of the imaginary friends that Sarah played with. Corde remembered Sarah had created himafter the family attended the funeral of Corde’s father and the minister had lifted his arms to the sun, speaking about “souls rising into heaven.” It was Sarah’s first experience with death and Corde and Diane had been reluctant to dislodge the apparently friendly spirit she created. But in the past year, to the parents’ increasing irritation, the girl referred to him more and more frequently.

“He made Redford T. Redford fly out to the forest and he told me—”

Diane’s voice cut through the yard. “No more of this magic crap, do you hear me, young lady? What were you doing?”

“Leave me alone.” The tiny mouth tightened ominously.

Corde said, “It’s going to be okay, honey. Don’t worry.”

“I’m

not

going back to school.”

Diane whispered in a low, menacing voice, “Don’t you ever do that again, Sarrie, do you understand me? You could’ve been killed.”

“I don’t care!”

“Don’t say that. Don’t ever say that!” Mother’s and daughter’s strident tones were different only in pitch.

Corde touched his wife’s arm and shook his head. To Sarah he said, “It’s okay, honey. We’ll talk about it later.”

Sarah bent down and picked up her knapsack and walked toward the house. With boundless regret on her face, she looked back—not however at the ashen faces of her parents but toward the road down which the silver truck was hurrying away without her.

They stood in the kitchen awkwardly, like lovers who must suddenly discuss business. Unable to look at him, Diane told him about Sarah’s incident at school that day.

Corde said contritely, “She didn’t want to go today. I drove her back this morning and made her. I guess I shouldn’t have.”

“Of course you should have. You can’t let her get away with this stuff, Bill. She uses us.”

“What’re we going to do? She’s taking the pills?”

“Every day. But I don’t think they’re doing any good. They just seem to make her stomach upset.” She waved vaguely toward the front yard. “Can you imagine she did that? Oh, my.”

Corde thought:

Why now? With this case and everything, why now?

He looked out the window at Sarah’s bike, standing upright on training wheels, a low pastel green Schwinn, with rainbow streamers hanging pathetically from the rubber handle grips. He thought of Jamie and his high racing bike that he zipped along on fast and daring as a motocross competitor. Sarah still couldn’t ride her tiny bike without the trainers. It embarrassed Corde when the family pedaled to town together. Corde tried to avoid the inevitable comparison between his children. He wished whatever God had dished out for them had been more evenly divided. It was difficult but Corde made a special effort to limit the pride he expressed for Jamie, always aware of Sarah’s eyes on him, begging for approval even as she was stung by her own limits.

A more frightening concern: some man offering a confused little girl a ride home. Corde and Diane had talked to her about this and she’d responded with infuriating laughter, saying that a wizard or a magic dog would protect her or that she would just fly away and hide behind the moon. Corde would grow stern, Diane would threaten to spank her, the girl’s face became somber. But her parents could see that the belief in supernatural protectors had not been dislodged.

Oh, Sarrie

…

Although Bill Corde still went to church regularly he had stopped praying. He’d stopped exactly nine yearsago. He thought if it would do anything for Sarah he’d start up again.

He said, “It’s like she’s emotionally dis—”

Diane turned on him. “Don’t say that! She has a high IQ. Beiderson herself told me. She’s faking. She wants to get attention. And, brother, you give her plenty.…”

Corde lifted an eyebrow at this.

Diane conceded, “Okay, and so do I.”

Corde was testy. “Well, we’ve got to do something. We can’t let that happen again.” He waved toward the yard, like Diane reluctant to mention his daughter’s mortality.

“She’s got her end-of-term tests in two weeks.”

“We can’t take her out of

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher