![The Rembrandt Affair]()

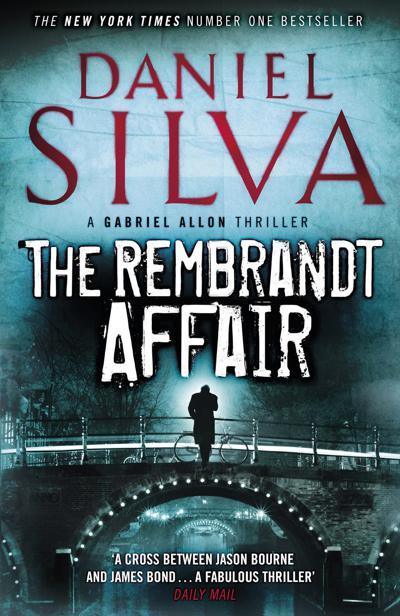

The Rembrandt Affair

Gabriel pressed a photograph of the painting into her hands. For several seconds, Lena Herzfeld’s face betrayed no emotion other than mild curiosity. Then, bit by bit, the ice began to crack, and tears spilled down both cheeks.

“Do you remember it now, Miss Herzfeld?”

“It’s been a very long time, but, yes, I remember.” She brushed a tear from her cheek. “Where did you get this?”

“Perhaps it would be better if we spoke inside.”

“How did you find me?” she asked fearfully, her gaze still fixed on the photograph. “Who betrayed me?”

Gabriel felt as if a stone had been laid over his heart.

“No one betrayed you, Miss Herzfeld,” he said softly. “We’re friends. You can trust us.”

“I learned when I was a child to trust no one.” She looked up from the photograph. “What do you want from me?”

“Only your memory.”

“It was a long time ago.”

“Someone died because of this painting, Miss Herzfeld.”

“Yes,” she said. “I know.”

She returned the photograph to Gabriel’s hand. For an instant, he feared he had pushed too far. Then the door opened a few inches wider and Lena Herzfeld stepped to one side.

Treat her gently, Gabriel reminded himself. She’s fragile. They’re all a bit fragile.

17

AMSTERDAM

G abriel knew the instant he entered Lena Herzfeld’s house that she was suffering from a kind of madness. It was neat, orderly, and sterile, but a madness nonetheless. The first evidence of her disorder was the condition of her sitting room. Like most Dutch parlors, it had the compactness of a Vermeer. Yet through her industrious arrangement of the furnishings and careful choice of color—a glaring, clinical white—she had managed to avoid the impression of clutter or claustrophobia. There were no pieces of decorative glass, no bowls of hard candy, no mementos, and not a single photograph. It was as if Lena Herzfeld had been dropped into this place alone, without parentage, without ancestry, without a past. Her home was not truly a home, thought Gabriel, but a hospital ward into which she had checked herself for a permanent stay.

She insisted on making tea. It came, not surprisingly, in a white pot and was served in white cups. She insisted, too, that Gabriel and Chiara refer to her only as Lena. She explained that she had worked as a teacher at a state school and for thirty-seven years had been called only Miss Herzfeld by students and colleagues alike. Upon retirement, she had discovered that she wanted her given name back. Gabriel acceded to her wishes, though from time to time, out of courtesy or deference, he sought refuge behind the formality of her family name. When it came to identifying himself and the attractive young woman at his side, he decided it was not possible to reciprocate Lena Herzfeld’s intimacy. And so he plucked an old alias from his pocket and concocted a hasty cover to go with it. Tonight he was Gideon Argov, employee of a small, privately funded organization that carried out investigations of financial and other property-related questions arising from the Holocaust. Given the sensitive nature of these investigations, and the security problems arising from them, it was not possible to go into greater detail.

“You’re from Israel, Mr. Argov?”

“I was born there. I live mainly in Europe now.”

“Where in Europe, Mr. Argov?”

“Given the nature of my work, my home is a suitcase.”

“And your assistant?”

“We spend so much time together her husband is convinced we’re lovers.”

“Are you?”

“Lovers? No such luck, Miss Herzfeld.”

“It’s Lena, Mr. Argov. Please call me Lena.”

The secrets of survivors are not easily surrendered. They are locked away behind barricaded doors and accessed at great risk to those who possess them. It meant the evening’s proceedings would be an interrogation of sorts. Gabriel knew from experience that the surest route to failure was the application of too much pressure. He began with what appeared to be an offhand remark about how much the city had changed since his last visit. Lena Herzfeld responded by telling him about Amsterdam before the war.

Her ancestors had come to the Netherlands in the middle of the seventeenth century to escape the murderous pogroms being carried out by Cossacks in eastern Poland. While it was true that Holland was generally tolerant of the new arrivals, Jews were excluded from most segments of the Dutch economy and forced to become traders

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher