![The Six Rules of Maybe]()

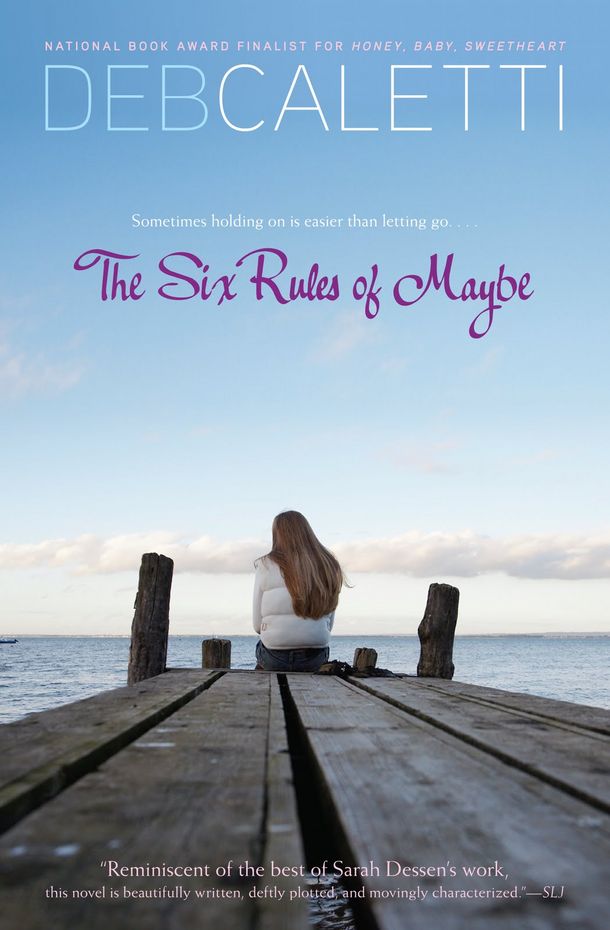

The Six Rules of Maybe

had always worked before, but I still felt some ugly feeling in my chest, something metallic and twisted, some kind of wreckage. I tried to untwist and understand. It didn’t feel good. It felt a little close to hate. Maybe I was hating Juliet, and it felt wrong to hateJuliet. Maybe what I hated was that Juliet could do no wrong even when she did one of the biggest wrongs.

The arguing couple made up, took hands, and then kissed deeply by the shore, the water wetting their shoes. The old lady appeared with her dog and they walked a bit, and then she picked him up just before he headed toward a glittery pool of broken glass. Maybe I had also always felt sure of something I wasn’t so sure of now. That if I followed some rules of being nice and good, everything would work out okay. That at least this meant I was giving fate its best shot to follow through the way it should. Good people would get good things; wrong acts were punished. You’d get back what you gave, because that was only fair. Maybe being good to other people was often really only about hope—your hope that if you acted the right way, the pieces of the universe would fall into their true and just place. If you were being honest, that was a good part of why you did it, right? It was a way to protect yourself. Sort of a shield against wrongness, only maybe wrongness just didn’t care about rules or hope or other people’s good intentions.

I sat there for a long time, until everyone had left and there were only two guys smoking cigarettes on the beach. The shadows were getting long and night was falling, and so I finally left. I went down to the marina and picked up a hamburger and fries and a shake at Pirate’s Plunder, because I tended to catch other people’s food choices, same as a yawn. I ate it in Mom’s car with the windows rolled down so the lingering french fry smell didn’t give away what I’d actually done with my night.

The TV was on in the living room but the lights were off when I got home. I didn’t want to catch Juliet and Hayden making out, so I crept upstairs. There was a crack of light under my mom’s door. I made my way over the creaks in the hall, shut my door by turningthe handle oh-so-quietly.

There was a tap then.

“Scarlet?”

“Yeah.”

Mom poked her head in. “You okay?” One hand was on the doorjamb, the other at her side. Plain, ringless hands. She never wore rings. I had asked her why, once. She had said she liked her hands to belong to herself.

“Yeah.”

“You don’t seem okay. Can I come in?” I nodded. She sat on the edge of my bed. She looked up at my wall of photos—Mrs. Martinelli in her frog sweatshirt, the back of Nicole and her mom looking into their refrigerator, Buster standing around with Ginger, as if they were catching up on dog gossip, a little girl staring with wide eyes into Randall and Stein Booksellers as if it were a toy store.

“I like that one,” she said.

“This?”

A shot of Goth Girl’s Mona Lisa . The Saint Georges’ lawn took up the top half of the frame; the painting filled the bottom.

“Next to it.” It was the back of Mr. Martinelli’s neck. The straight line of his crew cut set against a blue sky. “You’ve got a really good eye, you know.”

“Thanks.”

She tucked her brown hair behind her ears, and then tucked it again, as if she were about to deliver some bad news. She opened her mouth to say something, shut it for a revision, tried over. “I know this is hard. This stranger, coming and moving into our house … His dog. All this with Juliet. This situation thrust on us. I know that even I don’t understand how this happened.”

I looked down at my comforter. Traced the threads with myfinger. Boy, was she getting it wrong.

“It’s new for me, too,” she went on. “We don’t even know anything about him. And then, a baby …” She sighed. “God. She’s so young. I think about how young I was… .”

I tried to imagine this, a younger version of my mom, pregnant with Juliet. Some stranger with white-blond hair who spoke and ate and made decisions and maybe loved Mom and maybe didn’t. Twice in one day was more than I’d thought about him in years.

“I don’t understand how she could do something so stupid,” I said.

Mom thought. “Well, sometimes … you think it’s going to decide something. Marriage. A baby.”

I didn’t know where she was going with that. Mom could be fond of misty and beside-the-point musings. The kind

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher