![The Six Rules of Maybe]()

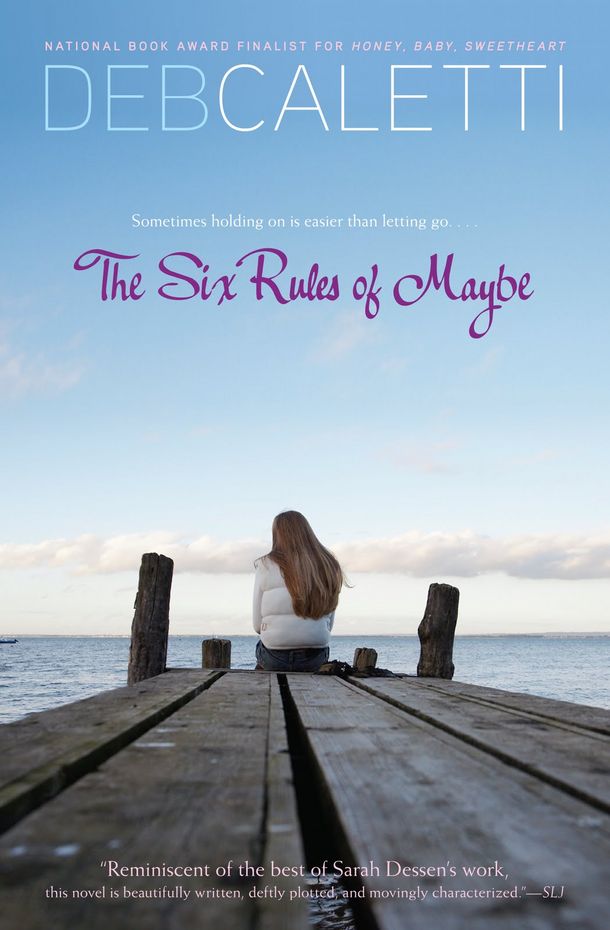

The Six Rules of Maybe

pale. Unwell. She didn’t say anything. She just looked at that envelope in her hands.

I had to ask her. I had to. “Buddy’s not …” I didn’t know if I could say it.

“Not what?”

“Buddy’s not Jitter’s father, or anything, is he?”

“Oh for God’s sake, Scarlet,” Juliet spat. “For God’s sake. Just … get out of here, would you? Get.”

And so I did. I got out of there. I left her alone with all the things she wanted and wanted and wanted.

I hadn’t seen Clive Weaver for days. His house sat so quiet, it mightas well have been boarded up. The newspapers gathered on his porch. I sniffed around the outside, hoping I didn’t smell something bad like people always did in the crime books, when the neighbor’s gone missing.

I wondered if I should deliver the Make Hope and Possibilities Happen for Clive Weaver project sooner than I’d planned. I had folded more than a hundred paper cranes and had twenty or thirty pieces of mail ready for his box. I wasn’t anywhere near my goal yet, and when I closed my eyes I saw it playing the way I imagined, loads of mail, loads of it. Well then, something else had better be done now. A person ought to check up on him anyway.

I went downstairs and made a quick batch of brownies. Too much fat and sugar was bound to be bad for his heart, yet he needed it for his spirit. I licked the bowl as I waited for them to bake, drank a big glass of milk that chased away the bad feelings I had about Juliet and Hayden and Kevin Frink and about Nicole, too, who had been nothing but cold to me since that day at the pool. I had wanted to help all of them, but it seemed like I was failing miserably.

I felt the way you did when you had been swimming for a long time, or running, or working on an endless research paper. Like the end was too far away, the obstacles too great, like you wanted to lie down and rest. But you didn’t rest, right? Or quit. You didn’t do any of those things that meant giving up, because quitting was for losers and babies, for the weak and lazy, for people with no backbone. You persevered, even if there were setbacks and you were tired and didn’t want to do any of it anymore. If you wanted some sort of triumph, you had to be persistent. You had to pay with all of your endless efforts. You had to stick with it. You just worked harder to make it happen, whatever “it” happened to be.

The chocolate was catching up to me.

I cut the brownies into squares and put them on a plate. I carried them outside, their warmth steaming up the Saran Wrap I had stretched over them. But it was true, wasn’t it? It was practically un-American to not set goals and then do everything you could, everything, to reach them. Quitting —it was a dirty word in a place where pilgrims had endured harsh winters and where pioneers had struggled through death and disease to create new lives. Giving up or stepping back or setting aside something you thought you wanted—it was almost a shameful act. I wasn’t one of those people who gave up easily. Sometimes it was confidence and not the lack of it that made me want to fix the bad I saw around me. I believed in the power a person had to change things.

Clive Weaver’s blinds were drawn, and the house looked very still. I was surprised, then, when the front door opened and Ally Pete-Robbins stepped outside, holding an empty Bundt pan. She looked at my brownies, and I looked at that pan. I wondered if I could see my future in its curved Teflon surface.

“His condition is worsening,” Ally Pete-Robbins said. But she sounded snippy. My brownies were invading her Bundt cake turf.

“Oh no,” I said.

“He has dishes out from days ago,” she said.

“Maybe somebody ought to wash them,” I said.

“I already did.” Her words closed the conversation. Her shoes clipped back down the sidewalk, sounding useful and efficient. I loved that sound, I had to admit, especially when my own heels were making it. Heels on sidewalks or shiny floors—the sound of important business.

But I wasn’t so much in the mood for visiting anymore. The Saran Wrap was coming unstuck around the edges of the plate, and my stomach felt too full from uncooked batter. I rang the bell,though, and when Clive Weaver answered in his bathrobe, his old face unshaven, his breath smelling sour, some mix of coffee and soup in cans, I only handed him the plate and said a few words I can’t remember now. Clive said, That’s mighty kind of you, mighty

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher