![The staked Goat]()

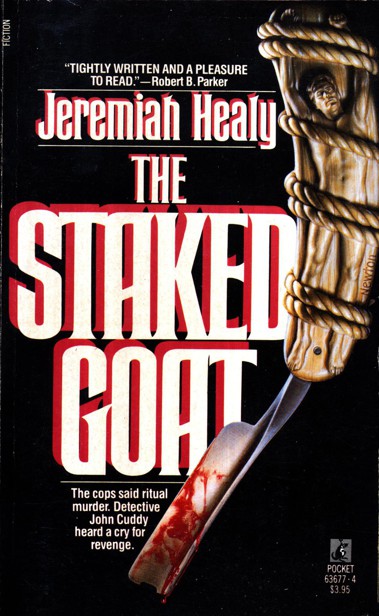

The staked Goat

Marco.

I left and locked the car and knocked on the Coopers’ back door. They let me in, Jesse selfconsciously cradling the shotgun in his good hand. Emily had been crying.

”Did the telephone ring since I spoke with you?” Emily said ”Twice,” sobbed and turned away. Jesse looked at me helplessly.

”Come on,” I said moving toward their telephone. They sat in front of me on their couch as I began to dial.

First, I called a friend at New England Telephone’s business office and set the wheels in motion for a changed, unlisted number. Jesse looked at Emily, who managed a small smile.

Second, I called the guy at the insurance company that I was working for when I nailed Marco’s brother.

I gave him a five-minute lecture on the good citizenship of the Coopers and how much money their cooperation had helped his company to save on the 1 claim. I asked him to approve a private security guard 1 for the Coopers. He said he doubted his boss would I go for it but he’d try. He said he would call me at f home with the answer.

I checked the white pages. There were fifteen | D’Amicos in the book, but there was only one on J Hanover Street, in the North End. I called the I number and got a heavily accented, older voice. I j said, ”Sorry, wrong number,” and hung up. I

I looked up at Jesse and Emily. They seemed much 1 brighter. I sighed and told them a close friend from the army had died here in Boston and that I had to go to Pittsburgh.

Jesse nodded gravely, thinking, I expect, of his own 1 outfit from World War II. Emily squeezed his good | hand tighter.

I told them to call me again if anything more happened. They said they would and thanked me again for all I had done for them.

All I had done for them.

I got in my car and started toward the North End via the Central Artery. I felt anger toward the elder D’Amicos for no good reason. I decided to cool off a little first with a different kind of visit.

* * *

In February you can’t see any sailboats from her hillside. Her first year there, we had an early spring. Then, a few brave souls, probably amateurs, were out by the last week of March.

”This year, I’d bet April 10th at the earliest, Beth.”

Before she’d gotten the cancer, or at least before we knew she had it, we would visit Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts once every few months. I always preferred paintings, Beth sculpture. Whenever we entered a room of sculpture, she would stand for fifteen minutes in front of one piece, say a smallish Greek statue, while I would wander around the room. Whenever I got back to her, she would be ready to go on to the next room. She always said she preferred studying one piece of work in detail. I never had the patience to stare at one piece of stone for that kind of time.

Until I lost her.

For months after Beth was buried, I would look only at her ground, not the headstone. Now I would notice the slightest additional scratch on her marker. A relative of hers, an old man, advised me at the wake to shy away from polished marble. He said that, despite its hardness, it always showed nicks and after ten months would look like it had been in the graveyard for ten years.

He may have been right. I tried to believe the marks around her name and years were natural aging, caused by cold and rain or windblown branches. More likely, they were the product of carelessly swung rakes or tossed beer bottles. But, she gently reminded me, I wasn’t keeping to the point.

”You’re right, kid. Al, Al Sachs, is dead. I identified the body this morning. Someone tortured and mutilated him, Beth. The police are treating it as a gay murder, but I don’t think so. He called me Tuesday morning and planned a dinner with me. He sounded nervous. No, more than nervous, scared.” I thought about that. In Vietnam we’d both been scared often enough, but I could never remember Al sounding scared. That was the edge in his voice that I noticed but didn’t recognize yesterday.

”In addition to sounding scared, somebody searched his room. A pro. He left nothing out of order that anyone would especially notice.” I left out the part about the guy who might have checked my pink message slip.

”I don’t have the slightest idea why it happened, kid. He was living and working out of Pittsburgh for a steel company, and this was the first time he’d been in Boston for years.”

She told me it wasn’t my fault. Agreeing with her helped only a little. ”Anyway, I’m going to

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher