![The staked Goat]()

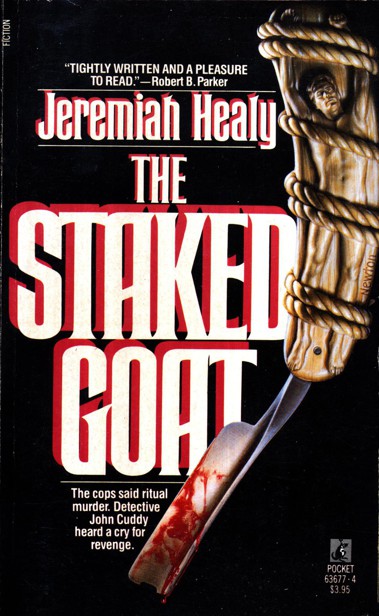

The staked Goat

halfway up the steps. ”Get started,” she said. ”I’ll be right down.”

Dale laid his parka on a chair, and he and I went into the kitchen. Carol had laid out the now-smaller spread in an appetizing fan around the table.

”Dale,” I said, ”do you have any idea where Martha would keep her aspirin? I got a little drunk after we got home, and I was just recovering from passing out when you knocked.”

My explanation was a bit elaborate for a mere aspirin request, but the dismissing of my and Carol’s shadow relationship seemed to relax Dale even more.

”Nooo, but”—he dug into the pockets of his pants and came up with a one-dozen tin—”I’m never without these.”

He popped the tin, and I thanked him for the two I took from it. I had washed them down with tap water, and Dale was halfway through his migraine tales when Carol reappeared in the doorway.

”Bad news, fellas,” she said, sagging her shoulder into the doorjamb. ”Kenny’s sick. Fever and sore throat. The last thing Martha needs now is a sick Al Junior, so I’m gonna take Kenny home right away.”

”No problem,” I said. ”I’ll stay here tonight and keep an eye on Martha.”

Carol nodded. ”I just looked in on her. She’s dead to the... she’s sound asleep. Little Al, too.”

Dale insisted on making her a sandwich to take back, and Carol went upstairs to bundle Kenny up. When she came back down, I walked her to the door.

”Here’s your sandwich,” I said, sliding it into her coat pocket. Kenny was completely concealed in a blanket. ”Would you like some help with him?” I said.

”No, thanks,” she said. ”Lean down, though, will you?”

I leaned down toward her, and she gave me a quick but a shade-more-than-friendly kiss on the lips. ”If you get lonely and want to talk, give me a call. I’m in the book. K-r-a-u-s-e.”

”I remember,” I said. ”Thanks.”

I opened the tundra turnstile, and she scooted outside.

When I got back to the kitchen, the vodka bottle was three fingers lower than I’d remembered leaving it. Dale sucked liberally from a tumbler with just ice and clear liquid in it. My vodka memories being too recent and still powerful, I chose a beer.

”I don’t know. I just don’t know....”

It was nearly eleven o’clock. Dale and I had polished off two sandwiches each. I was only on my second beer. The vodka tide was ebbing inexorably from the bottle and toward Dale. At first I thought he was suffering a post-funeral low. Then the conversation turned to Larry.

”I just don’t know,” said Dale for the third time. He had put in a tough couple of days, too, so I kept up my part of the conversation.

”Know what?”

”Oh”—Dale blinked and sucked up another mouthful of vodka—”life. The ‘where-is-it-all-leading’ problem. I’m forty-six years old. Larry’s twenty-nine. I love teaching and tutoring music, but if it weren’t for some family money, I’d... we’d... never have been able to afford the house. As it is, I don’t know what I’d do if I needed to buy a new car. I had a German car, a VW Bug, until three years ago. But after, you know, the recession, I couldn’t, I couldn’t stand not buying an American car with American steel. It’s not such a great car, but whenever I complain about what I’ve got or where I am, all I have to do is click on the TV or walk down the street. Do you know what this city’s unemployment rate is?”

”No,” I said. ”I don’t.”

Dale grimaced and took another gulp of booze. ”The official rate is fifteen, sixteen percent. Unofficially, counting the people who’ve been out of work so long they’re probably not in the computers anymore, the real rate now must be almost twenty-five percent. Walk down the streets, you’ll see them. Big, strong men in bowling jackets and baseball caps just standing on corners. Or waiting in line for any kind of job that’s listed. Their jobs, the industries that made their jobs real, are gone. Some gone to other countries, some just gone for good. A man who used to make steel can’t feed his family, but I can make a living teaching piano. You figure it out.”

”It is out of whack, a little.”

Dale sighed and seemed to run out of steam. Which was just as well, because I needed some answers before he slid into a different kind of trance. ”Dale—”

”No, not Dale,” he said. ”Stanislaw. That’s my real name. Stanislaw Ptarski. I grew up in a little town fifteen miles

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher