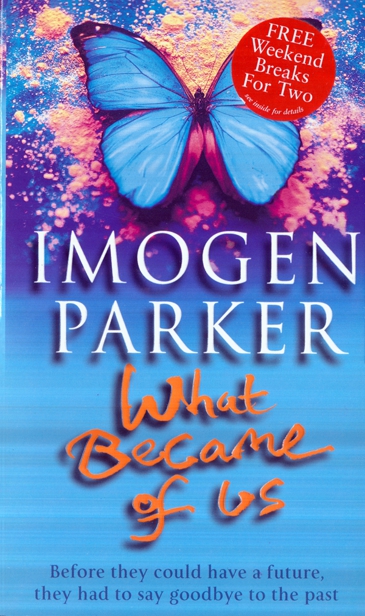

![What became of us]()

What became of us

neither of them from that day.

The loners had dotted themselves around the room in mathematical formation, like passengers in half-empty London tube carriage, each sitting as far from the others as possible, each pretending to be deeply immersed in a book. Manon could remember only Annie because her hair was peroxide white and her book was Kinflicks rather than the dusty volumes of Milton or Livy the others seemed to be studying. At one point in the interminable wait, Annie had caught Manon’s eye as she glanced furtively round the room and attempted to engage her in a complicit smile of exasperation, but Manon had looked away, too shy to respond. That initial failure to communicate had set the pattern of their relationship ever after. Twenty years later both of them had changed beyond recognition, but Annie still made showy attempts to be friendly, and still Manon inadvertently rebuffed her.

Annie was uncertain how to speak to her now that she was a hat check girl at the Compton Club, even though she had been instrumental in getting her the job.

‘Manon and I shared a house when we were at Oxford,’ she would announce to whoever was accompanying her when she came in.

‘You will come up and have a drink with us later, won’t you?’

She always made the offer with such enthusiasm, it would have been rude for Manon to decline, so she usually replied, ‘I’d like that’ or, ‘Yes, perhaps later.’

And Annie would smile over-eagerly for just a moment too long before turning, flustered, and hurrying up the stairs talking in an even louder voice than usual.

Twenty years earlier, Annie had arrived for her Oxford interview by bus too. Both of them assumed that all the other prospective students had a parent waiting outside the college in a smart Volvo, or anxiously drinking tea in the Randolph lounge but somehow even that shared experience had not created a bond between them.

Manon headed for the exit that led out almost opposite Worcester College. She had to dodge out of the way of a red sports car as she crossed over to Walton Street.

She had always loved the area known as Jericho. It was tatty and human, and so different from the forbidding stone colleges on St Giles just a couple of hundred yards away.

For Manon who had spent all of her education imprisoned in unforgiving institutions, Oxford had been an unfortunate choice of university, but the house in Jericho, which she had shared with Penny, Ursula and Annie for their second and final years, was one of the places that she had been happiest in her life.

The house belonged to Penny’s parents, who lived in a village about an hour away from Oxford . Penny’s mother often popped in on one of her shopping trips to the city, but Penny was deemed sensible enough to be left in charge of the tenants and rent arrangements. Manon was the last of Penny’s friends to be invited to share and so had the smallest room, above the front door. It was the first time in her life she had charge of a little piece of space that was her own.

When her own parents had been together they lived in barracks, and after the divorce she and her mother had moved to a cramped rented apartment in Paris with a shared toilet two floors down. The rest of her life she had spent in a dormitory at school.

Manon’s father was in the army. During her youth he had been posted in Hong Kong which she could not remember, and Germany which she could, because her mother had been so wretched there. They had not seen him since she was twelve years old when he had thrown her mother out, blaming her drinking for ruining his promotion prospects, and giving himself the perfect excuse to move in his brassy girlfriend. Her mother had used the meagre divorce settlement to keep Manon at her boarding school, mistakenly believing that a proper English education was the best thing she could give her. She herself had returned to Paris, depressed and unable to quit the bottle that had become her consolation as a lonely army wife.

Manon strolled along Walton Street. Everything was uncannily as it had been. On her left, the Phoenix cinema where she had sometimes gone to movies that started at midnight, returning home refreshed to write an essay for the next morning’s tutorial. On her right, the best cheap Indian restaurant in town, still there, still serving callow youths their first really hot vindaloo. It was all so remarkably the same that when she turned into Joshua Street, she noticed immediately

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher