![When You Were Here]()

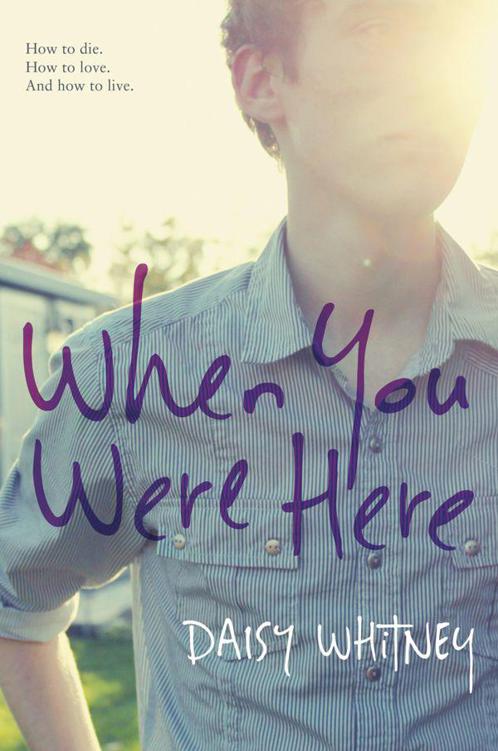

When You Were Here

are clearly new—Holland’s letter. Were they all sent to the address of this apartment? Or did my mom bring them on her last few trips to have them with her when she was here? I wish these notes came with a code to decipher them.

But that’s it for the Personal pile. A note from the daughter who deserted the family, a note from the dad who’s long gone, and a note from the ex-girlfriend. All these people who didn’t live with her for the last several years. All these people who weren’t there every day.

But nothing from me. Nothing for me.

I could tell myself this is a mere Post-it note from Kana, that it’s no big deal to be excluded from this pile. But it’s not just a Post-it note. It’s a collection of things that mattered to my mom. That she must have assembled over the years, gathered together near the end.

I head to the bathroom, yawning as I fumble for the light. Jet lag is kicking in quickly, threatening to smother me into sleep. I slide open the medicine cabinet, and it’s filled with prescription bottles. Bleary-eyed, I reach for one. It’s a cancer drug, and it’s barely been touched. Thenanother kind. This one was marked “open” on Kana’s list, but it looks like nearly all are still in the bottle, like my mom hardly took any. I know these drugs by heart, know their side effects and their benefits.

What I don’t know is why they’re full.

I remind myself that Takahashi can explain this. Takahashi, the last great hope, the supposed miracle doctor— brilliant and compassionate , my mom used to say—will tell me. Rules or no rules. He hasn’t called back yet, but I’ll go to his office tomorrow.

I grab another bottle. It’s Percocet, and it was filled by a pharmacy here several months ago. But even in my barely awake state, I can tell that none were taken either.

Ah, but perhaps this is what my mom left for me. Perhaps this is the Personal for the son. Yes, a gift from beyond, a beautiful parting gift indeed, because these work wonders on the living. It’s such a shame to waste a perfectly good numbing agent. I open the cap and free one of these beauties. I put the pill on my tongue and it feels like blasphemy—taking my mom’s painkillers when she was in real pain. But then I do it anyway, swallowing it dry.

I return to the living room, picking up the note from my dad, the card from my sister, the letter from Holland. I fold them all up and put them in my wallet to keep with me at all times.

They are foreign words to me now, but soon, soon , I’ll know how to translate them. I have to. Really, I have to.

Chapter Eleven

Jet lag wins.

The sun has barely risen, but I’m wide awake, ready for this city to unlock secrets. I shower, pull on shorts, a T-shirt, flip-flops, and sunglasses, and jam my wallet and phone into my pocket. It’s too early to meet Kana, too early to find the doctor, so I take the subway to the Tsukiji Fish Market, the largest fish market in the world, stretching along several blocks and all the way out to the Tokyo Bay.

I walk along the edge, where I can hear the merchants inside, sloshing around in their knee-high boots in the fishy water that puddles on the concrete floor as they peddle everything from mackerel to eel to shrimp to salmon to octopus to tuna that was just sold at auction a couple hours ago. I reach the block of food stalls on the outskirts of themarket, each one no more than a few feet wide. A red awning with Japanese characters falls over a stall selling fish crackers and dried oysters. Another with bamboo walls is flush against the sidewalk and offers up tempura and soba noodles heated in metal pots.

I find that food stall easily. My first stop. My first order of business. Not just breakfast but maybe a bit of information.

I grab a stool, order, and am quickly distracted from my mission by the taste of raw tuna. It feels like ages since I’ve enjoyed food, since I’ve tasted something that made me want food for more than just hunger.

My chopsticks dive into the bowl again, scooping up another heaping spoonful of rice and soy sauce and raw fish. A businessman next to me hungrily spears his breakfast fish too. I look behind the counter, hoping to see Mike. He’s this young dude, maybe twenty, who worked here last summer when I visited. He was into music, always playing some cool Japanese tunes on low on his little stereo while he served up fish. We’d sometimes trade song recommendations. If he’s here, I’m going to ask

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher