![When You Were Here]()

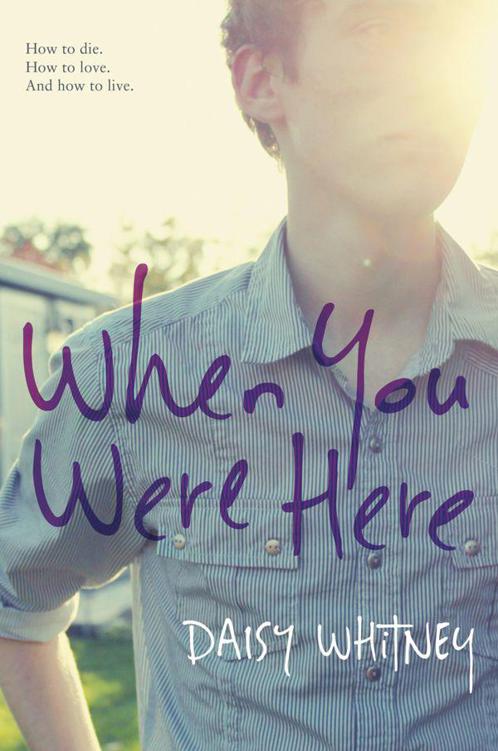

When You Were Here

not sure how to finish the line out loud. To see if I can ever be happy, or even remotely human, again. Would you happen to have the magic cure? “To see Tokyo again.”

“How’s she doing?”

There it is. The point in the conversation where we all become uncomfortable. That all-too-familiar moment when I have to tell someone for the first time. Like I had to do several weeks ago with the guy at the coffee shop in SantaMonica we used to go to, then the gal at the little pet-food shop around the corner from our house, and now here, with Mike.

“Actually she died a few months ago,” I say, the words still clunky and awkward. They probably always will be. “Back in April.”

Then the look. The tilt of the head, the heavy oh , like they’ve said the wrong thing. “Oh, man. I’m really sorry to hear that.”

“Thanks.”

“Damn, I’ll miss her. You know, she was here every day when she was in town.”

“Yeah, she dug this place.”

“She talked about you all the time when she was here. Said you got into UCLA and that you were kicking ass at school.” Then he points from me to him, and we’re back to regular chatter, and says, “She even passed along some of your new finds to me. Like that band Retractable Eyes.”

“That’s a good band,” I say, and I find it strangely cool that my mom channeled some of my music taste to the guy who served her breakfast. I find it even cooler that she talked to him about me. This is better than the Personal pile.

“They’re awesome. Anyway, she was our favorite customer. We loved those crazy wigs.”

“What was she like when she was here?” I ask because I’m hungry for more of this kind of sustenance. Apartment logistics are one thing; stories are another entirely.

Mike pauses to consider, wiping his hand on his apron. “The same as all the other times. She came here, had her breakfast bowl, talked about whatever movie she saw or book she was reading or her family, that kind of thing. She didn’t seem like someone who was sick. I mean, I knew she was sick because we talked about stuff, but you would never have guessed from how she acted, know what I mean?”

I nod a few times, glad to know my memory of her aligns with others’. “Yeah, that sounds like her.”

“She was always in a good mood too. Especially that time your sister came with her. Nice gal, your sister.”

And there goes the pitch. Like the batter just whacked my best curveball out of the park, and I never even saw it coming. Because my mom didn’t mention Laini’s visit, and my sister didn’t say anything either. I feel a searing pang of jealousy pound into me, thinking Laini might have been out here for my mom’s treatments, maybe her last treatment with Takahashi, and that Laini was helping to take care of her. That was my role, my job. Laini didn’t drive my mom to the hospital; she didn’t clean the bathroom when my mom had vomited in the middle of the night; she didn’t take her toast for breakfast the day after a chemo. Why did she get to be a part of my mom’s life over here and I didn’t?

“When was my sister here?” The words feel bitter on my tongue. I e-mailed her earlier in the week to give her a heads-up that I’d be coming here. But evidently I don’t merit the same kind of courtesy, since she never told me when she came to Tokyo.

Mike looks up for a second. “A few months back? Maybe January, maybe February?”

“That’s great,” I say to Mike, but it’s a lie. Because it’s not great that all the women I know, or knew, like to keep secrets. Holland and the way she left, my mom and the teahouse and the temple, now Laini with this visit I never knew about. I think secrets suck. I don’t like to keep them; I don’t like to share them; I don’t like to have them. I thank Mike and pay, and as I walk away I dial my sister’s cell phone, and it goes to voice mail.

But there is someone I can see now. The man who may know everything. It’s nine in the morning, and that’s when doctors’ offices open. A spark rises inside me as I catch another subway.

They are not here—my sister, my dad, Holland. The others in the Personal pile aren’t here at all.

But I am. And I can go, and seek, and ask.

Chapter Twelve

The doctor is in.

Or the doctor isn’t in.

Or the doctor isn’t in yet.

See, I don’t know, because there isn’t any sign on his door. There isn’t an OPEN or CLOSED sign. Or a BACK SOON sign. Or a Post-it note letting the next

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher