![When You Were Here]()

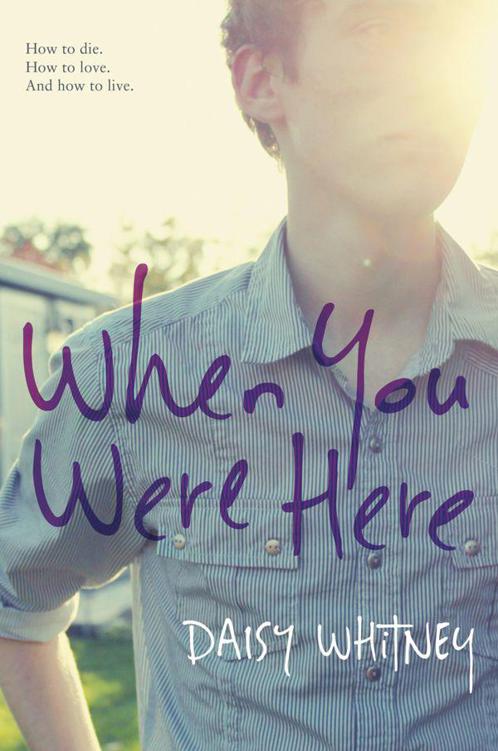

When You Were Here

him about my mom, what she was like in those final days over here. I’ll take an anecdote, a sliver of a tale, something, anything, that’ll bring her back in some small way.

Mike’s not here, though. Instead there is a hunched-over Japanese woman behind the counter, stirring a huge vat of miso soup, and I ask for a bowl of that too. She nods, then ladles out some soup for me.

I don’t even know if this place where I’m eating has aname. My mom would say, Let’s go to that food stall , and we’d swipe our subway tickets through the turnstiles and catch an early morning train to the fish market for breakfast. “If sushi cured cancer, I’d be in the clear,” she joked last summer over a bowl of tuna.

“Don’t say that, Mom. Besides, you will be in the clear soon.” She’d held cancer at bay for four years by then. She’d withstood countless rounds of chemo and surgeries. She was going to lick it, I was sure. No one was tougher than my mom. She’d managed the disease with laughter, and some tears, but mostly laughter.

“And then I will be at your graduation, and I will be wearing a neon wig then, not because I need it, but to embarrass you,” she teased.

“It would be totally embarrassing,” I said, but it also wouldn’t be. Everyone at school knew about my mom and her colorful wigs. The girls loved them. They would come up to me, tears in their eyes, and tell me how tough my mom was and how cool she was with her electric-blue wig, her candy-pink hair, her emerald-green curls, and so on.

“You should know I plan on hollering your name from the audience and throwing the most elaborate party in the world. Mark my words, as this bowl of tuna is my witness, I will be standing up and cheering at my son, Daniel’s, graduation. I may even bake a cake.”

“You don’t bake, Mom,” I said.

“I know. But I will for graduation. Or maybe I’ll just get one of those really awesome store cakes.”

I push the bowl away. I fix my eyes on the merchants down the street, who are adjusting their displays, to distract myself from the memory, from the failure of it to become reality. I stare so long that the things in front of me become blurry, as if I’m watching all the shopkeepers and food sellers from behind an antique camera while their lives pass by in sepia tone. Whatever pettiness I felt last night at being left out of the Personal pile has dissipated here at the fish market. Because now I’m just back to missing her. It feels embarrassing to admit that. I’m a guy; we’re supposed to be tough, strong. We’re not supposed to miss our mommies. But damn if I don’t miss her. Damn if I don’t miss having dinner with her, talking about the little things, like what app I just downloaded on my phone and whether I thought she’d like it too, or the bigger things, like what if I didn’t make it into UCLA, or even just talking about Sandy Koufax. My mom loved that dog like she was a third child. Whenever we’d come back from dinner out, since we ate out a lot, or a school event, or one of my mom’s treatments, Sandy Koufax would jump off the couch, stretch, then wag her tail and offer herself for petting.

“Oh, you are the cutest, sweetest, most adorable dog in the entire universe,” my mom would say.

The dog made her happy. As for me, just having someone to talk to made me happy. Now my voice barely gets used. And so I miss her, and the silence in my life reminds me of how much.

I’m jerked back by the buzzing of my phone. I glance at the screen. There’s a note from Kate. I e-mailed her yesterday, letting her know I landed safely. Are you at the fish market? Say hi to the tuna for me! Every time I look at the clock now I convert the hours to Tokyo time too.

I send a quick reply, letting her know the tuna says hello, and it feels vaguely comforting that Kate’s checking up on me. When I look up, the hunched-over old woman is whispering to someone in the cramped quarters at the back of the food stall. I lean to the side to get a better look. It’s Mike. He wears a white T-shirt, black chef pants, and an apron around his waist. An unlit cigarette rests behind his ear. I hold up a hand to wave. He tips his forehead in response, then walks over.

“How’s it going, man? I remember you. Elizabeth’s son, right?”

I nod. I’m glad he remembers me, that I don’t have to dive into a lengthy explanation or reminder. “Yeah, I’m just here for—” I stop for a second, because I’m

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher