![When You Were Here]()

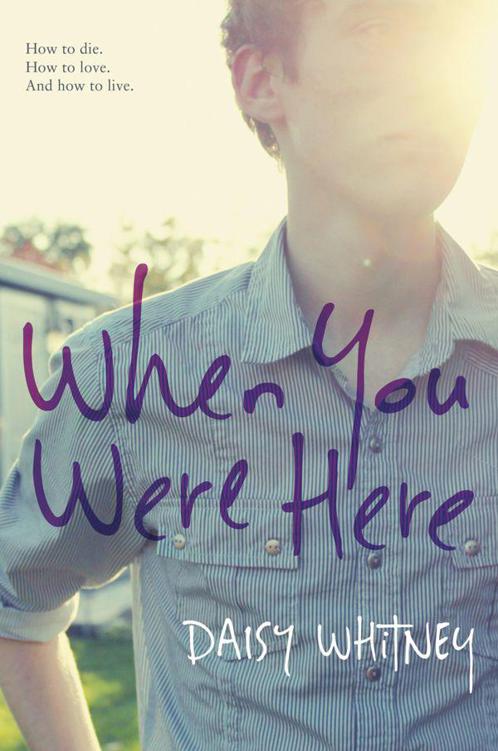

When You Were Here

the next thing, I come up short. “Were you going to keep her?”

“No. I don’t know. Maybe. I hadn’t decided.”

“Does your mom know?”

“Yes. Everything. I told her when I was, I don’t know, four months along. My dad never knew.”

“But my mom knew. She has a picture, Holland. Do you know that?”

No answer.

“Why does my mom have a picture of your baby, Holland? Why does my mom have a picture of Sarah?” I know the answer. There is only one answer. But the answer is so surreal, so foreign, so completely messed up. “Was she… Was Sarah…” I trail off. I can’t get mine to come out of my mouth. My tongue is tied.

Holland unties it with her answer. “Yes. She was yours.”

Forget the grenade. It’s like a dirty bomb exploding in my chest, shrapnel everywhere. I have so many more questions now that I know that answer, but I’m picking metal and glass out of my skin. And my voice is gone, it’s shot, my throat is dry and my lungs are closed and the food stalls fade, the counter is gone, the ladies in their beige dresses disappear, and I have been blasted back to some primordial state where I don’t have speech, I don’t have arms and legs and voice. I sink down to the floor of the department store basement, as people, so many people, an endless stream of people, walk past me.

“Danny.”

Holland is saying my name. She may have been saying it for seconds, minutes, years, eons. I focus again. The floor is concrete again, and the counters are full of food again, and the workers have shape again.

“I’m here.”

“I’m sorry,” she whispers into the phone. “I’m so sorry.”

Sorry? Is that what this is about? Sorry? There are so many more things to be said than sorry. They all start with Why. Why didn’t you tell me? Why didn’t you say anything? Why am I finding out now that I was a father? Why am I finding out now the kid died?

That blasted feeling returns, like the bomb Holland lobbed has ripped out my organs. I don’t even know how I’m supposed to take this, receive this, accept this, deal withthis. I don’t have a clue. You would think I’d be an expert, a professional griever at this point. That this would be second nature. That this would be my best subject, the class I excel at.

But the only thing I feel for sure is a sick form of relief. I’m eighteen years old. I’m about to start college. I don’t have a family. I’m the last person in the world who should have a child. The girl I love has been broken to pieces by this for the better part of a year, and I never knew it. But me? All I can think is, Thank God I don’t have a kid . I have dodged a bullet, one that was heading straight for my head.

I can’t say this to her. I can’t say this to anyone. A family walks past me. The mom glances over. She knows. She looks at me, and she can tell. I am a boy who had a kid he didn’t want, and the kid died, and there’s a part of him that’s glad.

How did I become this person? I do not like this person. “I can’t believe you didn’t tell me. I can’t believe you didn’t ask me what to do. I can’t believe you didn’t say a word. Then or ever.”

“I have been wanting to tell you for the last few weeks. Why do you think I e-mail you all the time? Why do you think I called you?”

“I don’t know. How am I supposed to have a clue?”

“I have been trying to explain everything.”

“You want to explain things? You want to explain things now? That sounds great. Why don’t we meet for coffeetomorrow, and you can tell me everything you’ve been trying to explain?” Then I hang up on her.

I drop my head between my knees, but I don’t think it’s Holland I’m mad at for not telling me. I’m mad at someone else. Someone I’ve never really been mad at before.

My mom.

Chapter Twenty-One

Holland worked at a camp every summer during high school, but it never seemed like work for her. She had a natural connection with kids. One day last year, I picked her up from camp, and she was sitting at the picnic table in front of the school where the camp was held. There was a little girl with her. Her parents must have been late picking her up or something, so I joined them at the bench, and Holland and the girl played tic-tac-toe for probably twenty minutes. The girl beat Holland in a round and did a little jig, then Holland beat the girl and held her toned arms up in the air victoriously. It went on like that—sometimes Holland let her win,

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher