![When You Were Here]()

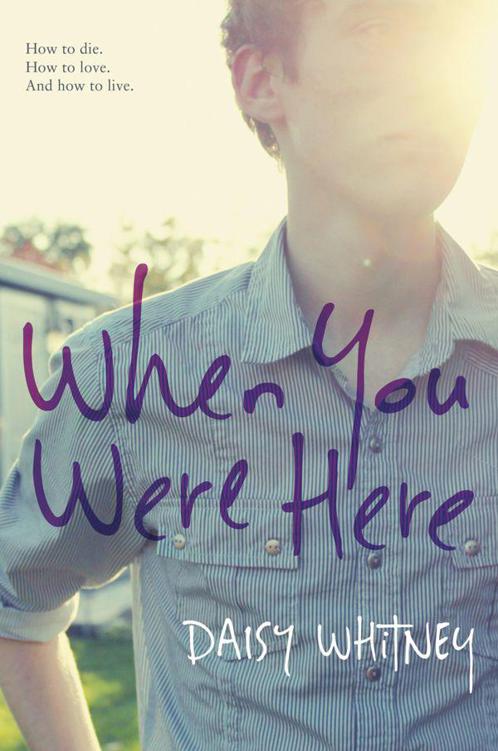

When You Were Here

it’s the thing I’ll happily take from the last great hope.

I race to meet Kana at our rendezvous spot near Yoyogi Park to tell her the good news. Takahashi is back from Tibet, and he will see me at the end of the week. The last piece, the last thing I came for. He can finally tell me what’s behind door number three.

“It’s like a pronouncement, Kana, like I’ve been granted an audience with the king,” I say, and I feel as if I can exhale, as if I’ve been holding my breath for this meeting.

She beams and raises her right arm straight, then speaks in a deep voice. “King Takahashi will see you now, Danny Kellerman.” Then she surprises me by imitating me, adopting some sort of exaggerated California boy drawl and making a hang-ten gesture. “Dude, so it is written, so it shall be.”

All I can do is roll my eyes, because she has schooled me, beaten me at my own game of Occasional Sarcasm.

When I return to my building, a blast of cold air greets me in the lobby. I will say this: Tokyo does air-conditioning well. It’s arctic inside my building, and it is epic. I consider myself something of an expert in air-conditioning. I have studied the fine difference in degrees, have meditated on sixty-eight degrees as the perfect cooling temperature compared to sixty-seven degrees. I have contemplated whethersixty-six is icebox frigid enough for me. And I have declared sixty-five to be my nirvana, so I crank the thermostat to that perfect temperature when I arrive upstairs. The familiar whirring of the machine begins, a comforting hum that will usher in the igloo effect. But the temperature doesn’t drop. The air isn’t any cooler.

Crap. My apartment will be a sauna in minutes if I don’t fix this. The air-conditioning unit is in a utility closet in the main bedroom. I open the door to my mom’s room, then to the closet, then I inspect the unit, popping off the cover easily. Right away I can tell the filter’s a mess, all dirty and clogged, and that’s why the air isn’t cooling down. It’s an easy fix, so I head back to the kitchen, grab the garbage can, and return to the bedroom. I find the extra filters right next to the machine—sending a silent thanks to Kana and Mai, because no one ever has filters when you need them, unless it’s your job to stock them—so I swap in the new one, tossing the old one into the trash. I put the cover back on and close the closet door. My dad was handy; he taught me to be handy too. I glance over at the framed photos of him, a reminder that he gave me this skill, that I can still find pieces of his life in me.

My eyes are drawn to the pile of photos I saw the other night on the lower shelf, next to the framed photo I’d been looking at of my mom and dad. I reach for them just to see what’s there, to see what photos never made it to frames. I flip through them. Mostly they’re doubles of ones that are already framed or they’re the bad shots—the ones with redeyes or the blurry ones or where the subject is out of focus. I’m about to toss them back onto the shelf when an image catches my eye. I’d recognize that hair anywhere. A lock of light blond hair, the slightest wave to it. It’s Holland; she’s barely in the frame at all, just the edge of her hair. She’s holding a white blanket wrapped around something. A throwaway photo, a mis-shot. But where’s the real one? Where’s the one that matches this, the one that tells the story this photo isn’t sharing?

I check out my mom’s shelves. I don’t see it. There are no framed photos of Holland. I look behind books. Still nothing.

What the hell? Why does my mom have a picture of her like that? Not a pose or a headshot or a vacation pic but a moment in time instead. I scan my mom’s desk. There’s not much on it, just some Post-it notes and pencils for her crosswords, some worn down, some sharpened. There’s a crossword-puzzle book off to the side of her desk. Something white, like a piece of white cardboard, is poking out the side. I grab the book and reach for the cardboard. It’s a stiff photo frame, not metal but the cardboard kind that stands open, with two photos in it. My hands tremble as I open the frame.

Two pictures. In one Holland is looking at the camera and smiling. There are machines nearby, and she’s holding something in her arms, wrapped in that white blanket, and a few tufts of brown hair poke out from the blanket. In the next photo, she’s turned the bundle around, and

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher