![When You Were Here]()

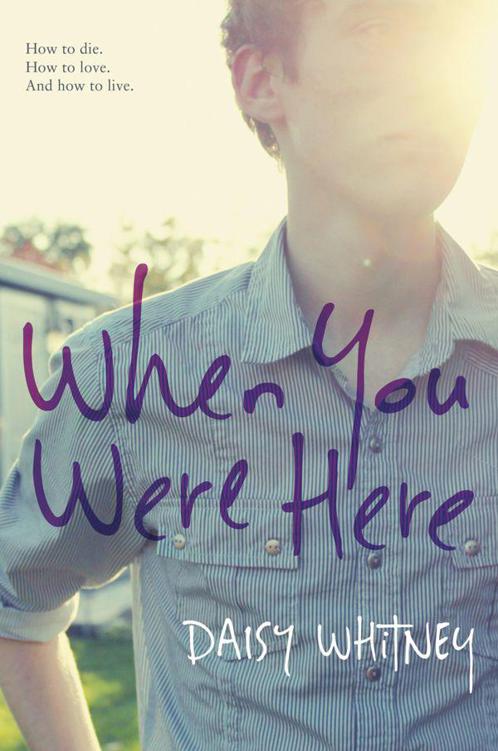

When You Were Here

inside thebundle is a tiny baby. The baby’s eyes are open, and Holland is kissing the baby’s head. Holland looks tired but happy.

My heart ricochets out of my chest and collapses on the floor when I read the name my mom has written.

Sarah St. James.

Sarah’s not a friend from college.

Sarah has Holland’s last name.

And a date of birth.

Six months ago.

Chapter Twenty

I stumble out of my mom’s room.

Six months ago Holland had a baby.

Sarah is six months old.

I fumble around for a Percocet. I find them on the coffee table. I take one. Then another. I leave. I pace through the streets of Shibuya, past arcades, past shops selling socks with hearts and rainbow stripes, past pachinko parlors where people are winning cat erasers and manga figurines. How can people want cat erasers and manga figurines at a time like this? I march past cell-phone stores and crepe dealers and a nail salon advertising decals of suns and moons and flowers, and I don’t understand how a nail salon can advertise suns and moons and flowers when there are too many things that don’t make sense.

Beads of sweat drip from my forehead. I wipe a hand across my face. My hand is slick. I reach for the bottom of my gray T-shirt and wipe my face with the fabric. But the sweat starts again, and when I look up at the time and the temperature outside the Bank of Tokyo, the red flashing sign blares ninety-seven degrees at one in the afternoon. That means it’s nine at night yesterday in Los Angeles.

I’m in front of a towering department store, eight floors high. A skinny Japanese woman in heels and a suit leaves, and a jet of cool air follows her. It’s an igloo inside. I need the igloo effect right now, so I take the escalator to the basement, a massive expanse of gourmet food shops and stalls selling European chocolates and bento boxes and fresh fruit for sky-high prices. The cool air sucks the heat off of me, and by the time I pass the pickled radishes and eggplants being sold by Japanese women in beige dresses with white caps like nurses wear, I’m able to take my phone from my pocket.

She answers on the second ring, and I hate that the sound of her voice takes my breath away. I am fighting a losing battle with her, drowning on dry land at the sound of her saying my name.

“Danny.”

I don’t bother with small talk. “Who is Sarah really?”

She stumbles on her words. “What do you mean?”

“I mean: Who. Is. Sarah? Why do you wear her name around your neck? Who is she? Where is she? Because I don’t think she was your friend at school. And I don’t thinkshe died,” I say as I walk past a young guy trying to sell me a sake set. I hold up a hand, my palm a stop sign to his peddling.

“Who do you think she is, then?”

I pass gift boxes of cherries and Asian mushrooms while her voice weakens across the phone line, across the distance from Los Angeles to Tokyo. “Your daughter.” A pause. What do I say next? “What the hell, Holland?”

Holland doesn’t say anything. I try to picture her. Where is she? At her house? At the day camp where she works?

“Did you give her up for adoption?”

“No.”

I stop walking. I place a hand on a counter to steady myself. There are red-bean pastry balls under the glass. No one asks me if I want to buy some. Everyone who works here can tell I’m not here to buy red-bean pastry balls. “You didn’t? You didn’t give her up for adoption?”

“No. I didn’t give her up.”

“Did she die?”

“Yes. She died.” I shift my stance, move away from the food, and lean back against a section of the brick wall. I look down at the gray concrete floor. “Shit, Holland. Why didn’t you tell me?”

No answer.

“What happened?” I ask softly.

“I went into labor when I was five and a half months pregnant. I was twenty-six weeks along. The baby was bornpremature. She was two pounds and one ounce and she was perfect in every way, except she was so small and she wasn’t supposed to be born yet. She was in the NICU for two days and she got an infection and she wasn’t strong enough to fight it off and she died.”

The words are heavy, rehearsed, like she’s said them before. I wonder if she has, and who she’s said them to, or if she’s just rehearsed them in her head, so she can get them out without choking on every single awful word, because they are awful, all of them, strung together like little grenades.

“God,” I say, but when I try to think of the next word,

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher