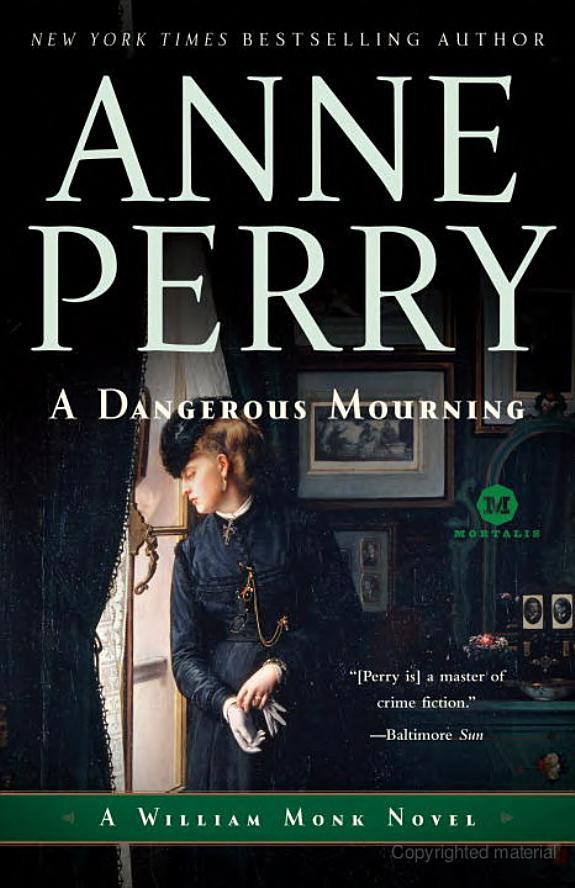

![William Monk 02 - A Dangerous Mourning]()

William Monk 02 - A Dangerous Mourning

“Lady Moidore has rather an active imagination. Like a lot of ladies. She gets her facts muddled, and frequently does not mean what she says. I am sure you understand that?” His tone implied that Hester would be the same, and her words were to be taken lightly.

She rose to her feet and met his eyes, so close she could see the shadow of his remarkable eyelashes on his cheeks, but she refused to step backwards.

“No I do not understand it, Mr. Kellard.” She chose her words carefully. “I very seldom say what I do not mean, and if I do, it is accidental, a misuse of words, not a confusion in my mind.”

“Of course, Miss Latterly.” He smiled. “I am sure you are at heart just like all women—”

“Perhaps if Mrs. Moidore has a headache, I should see if I can help her?” she said quickly, to prevent herself from giving the retort in her mind.

“I doubt you can,” he replied, moving aside a step. “It is not your attention she wishes for. But by all means try, if you like. It should be a nice diversion.”

She chose to misunderstand him. “If one is suffering a headache, surely whose attention it is is immaterial.”

“Possibly,” he conceded. “I’ve never had one—at least not of Romola’s sort. Only women do.”

Hester seized the first book to her hand, and holding it with its face towards her so its title was hidden, brushed her way past him.

“If you will excuse me, I must return to see how Lady Moidore is feeling.”

“Of course,” he murmured. “Although I doubt it will be much different from when you left her!”

It was during the day after that she came to realize more fully what Myles had meant about Romola’s headache. She was coming in from the conservatory with a few flowers for Beatrice’s room when she came upon Romola and Cyprian standing with their backs to her, and too engaged in their conversation to be aware of her presence.

“It would make me very happy if you would,” Romola said with a note of pleading in her voice, but dragged out, a little plaintive, as though she had asked many times before.

Hester stopped and took a step backwards behind the curtain, from where she could see Romola’s back and Cyprian’s face. He looked tired and harassed, shadows under his eyes and a hunched attitude to his shoulders as though half waiting for a blow.

“You know that it would be fruitless at the moment,” he replied with careful patience. “It would not make matters any better.”

“Oh, Cyprian!” She turned very petulantly, her whole body expressing disappointment and disillusion. “I really think for my sake you should try. It would make all the difference in the world to me.”

“I have already explained to you—” he began, then abandoned the attempt. “I know you wish it,” he said sharply, exasperation breaking through. “And if I could persuade him I would.”

“Would you? Sometimes I wonder how important my happiness is to you.”

“Romola—I—”

At this point Hester could bear it no longer. She resented people who by moral pressure made others responsible for their happiness. Perhaps because no one had ever taken responsibility for hers, but without knowing the circumstances, she was still utterly on Cyprian’s side. She bumped noisily into the curtain, rattling the rings, let out a gasp of surprise and mock irritation, and then when they both turned to look at her, smiled apologetically and excused herself, sailing past them with a bunch of pink daisies in her hand. The gardener had called them something quite different, but

daisies

would do.

She settled in to Queen Anne Street with some difficulty. Physically it was extremely comfortable. It was always warm enough, except in the servants’ rooms on the third and fourth floors, and the food was by far the best she had ever eaten—and the quantities were enormous. There was meat, river fish and sea fish, game, poultry, oysters, lobster, venison, jugged hare, pies, pastries, vegetables, fruit, cakes, tarts and flans, puddings and desserts. And the servants frequently ate what was returned from the dining room as well as what was cooked especially for them.

She learned the hierarchy of the servants’ hall, exactly whose domain was where and who deferred to whom, which was extremely important. No one intruded upon anyone else’s duties, which were either above them or beneath them, and they guarded their own with jealous exactitude. Heaven forbid a senior housemaid

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher