![William Monk 02 - A Dangerous Mourning]()

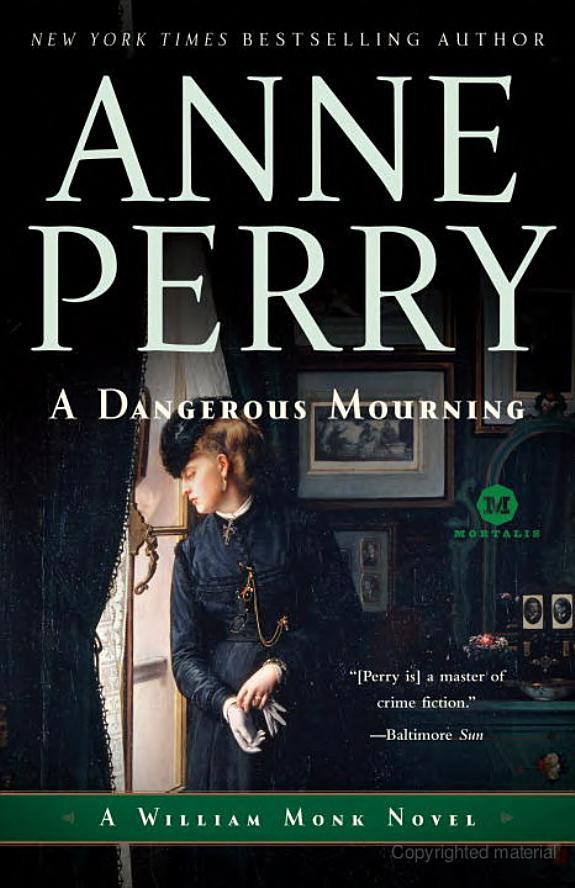

William Monk 02 - A Dangerous Mourning

yes—of course.” He blinked his washed-out blue eyes. “I do beg your pardon. Good afternoon, Miss Latterly.” He moved to get away from the cellar door, still looking extremely uncomfortable.

Annie, one of the upstairs maids, came past and gave Septimus a knowing look and smiled at Hester. She was tall and slender, like Dinah. She would have made a good parlormaid,but she was too young at the moment and raw at fifteen, and she might always be too opinionated. Hester had caught her and Maggie giggling together more than once in the maids’ room on the first landing, where the morning tea was prepared, or in the linen cupboard bent double over a penny dreadful book, their eyes out like organ stops as they pored over the scenes of breathless romance and wild dangers. Heaven knew what was in their imaginations. Some of their speculations over the murder had been more colorful than credible.

“Nice child, that,” Septimus said absently. “Her mother’s a pastry cook over in Portman Square, but I don’t think you’ll ever make a cook out of her. Daydreamer.” There was affection in his voice. “Likes to listen to stories about the army.” He shrugged and nearly let slip the bottle under his arm. He blushed and grabbed at it.

Hester smiled at him. “I know. She’s asked me lots of questions. Actually I think both she and Maggie would make good nurses. They’re just the sort of girls we need, intelligent and quick, and with minds of their own.”

Septimus looked taken aback, and Hester guessed he was used to the kind of army medical care that had prevailed before Florence Nightingale, and all these new ideas were outside his experience.

“Maggie’s a good girl too,” he said with a frown of puzzlement. “A lot more common sense. Her mother’s a laundress somewhere in the country. Welsh, I think. Accounts for the temper. Very quick temper, that girl, but any amount of patience when it’s needed. Sat up all night looking after the gardener’s cat when it was sick, though, so I suppose you’re right, she’d be a good enough nurse. But it seems a pity to put two decent girls into that trade.” He wriggled discreetly to move the bottle under his jacket high enough for it not to be noticed, and knew that he had failed. He was totally unaware of having insulted her profession; he was speaking frankly from the reputation he knew and had not even thought of her as being part of it.

Hester was torn between saving him embarrassment and learning all she could. Saving him won. She looked away from the lump under his jacket and continued as if she had not observed it.

“Thank you. Perhaps I shall suggest it to them one day. Of course I had rather you did not mention my idea to the housekeeper.”

His face twitched in half-mock, half-serious alarm.

“Believe me, Miss Latterly, I wouldn’t dream of it. I am too old a soldier to mount an unnecessary charge.”

“Quite,” she agreed. “And I have cleared up after too many.”

For an instant his face was perfectly sober, his blue eyes very clear, the lines of anxiety ironed out, and they shared a complete understanding. Both had seen the carnage of the battlefield and the long torture of wounds afterwards and the maimed lives. They knew the price of incompetence and bravado. It was an alien life from this house and its civilized routine and iron discipline of trivia, the maids rising at five to clean the fires, black the grates, throw damp tea leaves on the carpets and sweep them up, air the rooms, empty the slops, dust, sweep, polish, turn the beds, launder, iron dozens of yards of linens, petticoats, laces and ribbons, stitch, fetch and carry till at last they were excused at nine, ten or eleven in the evening.

“You tell them about nursing,” he said at last, and quite openly took out the bottle and repositioned it more comfortably, then turned and left, walking with a lift in his step and a very slight swagger.

Upstairs Hester had just brought the tray for Beatrice and set it down, and was about to leave when Araminta came in.

“Good afternoon, Mama,” she said briskly. “How are you feeling?” Like her father she seemed to find Hester invisible. She went and kissed her mother’s cheek and then sat down on the nearest dressing chair, her skirts overflowing in mounds of darkest gray muslin with a lilac fichu, dainty and intensely flattering, and yet still just acceptable for mourning. Her hair was the same bright flame as always, her

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher